Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

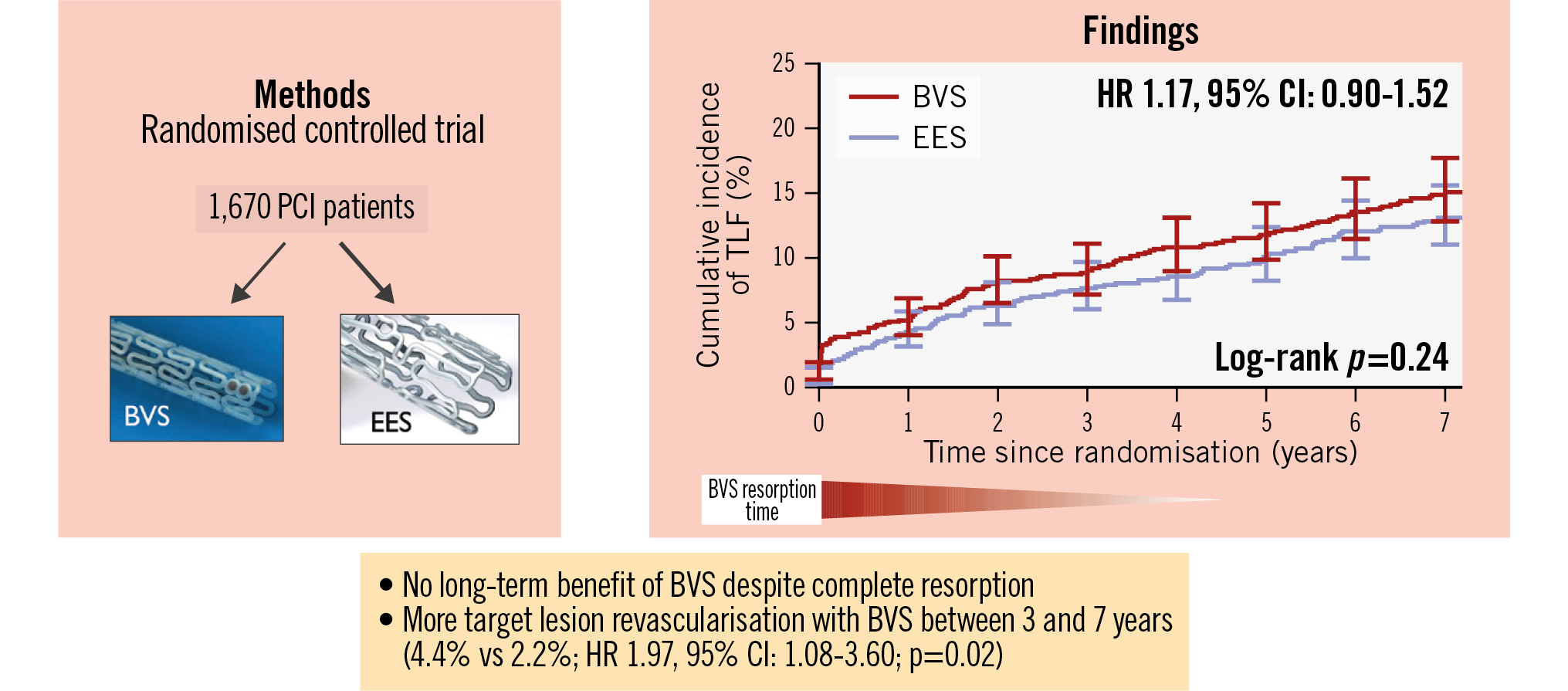

Background: The clinical outcomes of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) compared with everolimus-eluting stents (EES) beyond 5-year follow-up are unknown.

Aims: This study aims to investigate clinical outcomes of BVS 7 years after implantation.

Methods: The COMPARE-ABSORB trial is an investigator-initiated, prospective randomised study. Patients at high risk of restenosis were randomly assigned to receive either a BVS or an EES. A dedicated implantation technique was recommended for BVS. The primary endpoint was target lesion failure (TLF), defined as the composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (TVMI), or clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation (CI-TLR). The primary and co-primary objectives were non-inferiority at 1 year and superiority of BVS at 7 years after a 3-year landmark analysis.

Results: Although enrolment was stopped at 1,670 patients (80% of the intended 2,100 patients; 848 patients receiving BVS and 822 EES) because of high thrombosis and TVMI rates in the BVS arm, non-inferiority for TLF at 1 year was met. At 7-year follow-up subsequent to a 3-year landmark analysis, the TLF rate of BVS was 6.7% versus 5.9% for EES (hazard ratio [HR] 1.14, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.76-1.77; p=0.53); therefore, superiority was not met. Cardiac death, TVMI, and device thrombosis rates did not differ between both groups; however, CI-TLR was significantly higher in the BVS arm (4.4% vs 2.2%; HR 1.97, 95% CI: 1.08-3.60; p=0.023).

Conclusions: After complete resorption, no benefit was observed with BVS compared with EES at 7-year follow-up, despite the use of a dedicated implantation protocol for BVS. In fact, after 3 years, more target lesion revascularisations occurred with BVS than with EES.

Studies with second-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) have shown that after the initial 30 days, the target lesion failure (TLF) rate increases linearly up to 5- or 10-year follow-up, with an annual TLF rate of approximately 2.0%123. To improve the long-term outcome of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) patients by attempting to flatten this TLF event rate over time, new strategies with bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) or drug-coated balloons have been introduced. These “leave nothing behind” strategies have the potential to restore the physiology of the treated vessel segment by restoring pulsatility, vasomotion, remodelling, and removing the trigger for neoatherosclerosis that is caused by a permanent metallic implant, with or without a durable polymer.

Previous randomised trials comparing BVS with metallic DES resulted in BVS demonstrating higher rates of TLF and device thrombosis compared with metallic DES4567. These disappointing outcomes with BVS were mainly driven by events in the early phase and have been partially attributed to a suboptimal implantation technique, selection of small vessels, or to the mechanical limitations of this relatively thick-strut device resulting in less acute gain, despite an optimal implantation technique. A second wave of scaffold thrombosis around 3 years, though to a lesser extent compared with the early phase, has been described, mainly related to intraluminal dismantling of discontinuous or malapposed scaffold remnants89. These observations, and the fact that in all prior randomised ABSORB trials a BVS-specific implantation technique was neither fully developed nor employed as part of the study design, raised the question as to whether a BVS-specific optimal implantation technique can prevent these very late adverse events and whether very late adverse events originating from the treated coronary segments can be prevented when the scaffold is fully resorbed and the vessel is fully “uncaged”.

Furthermore, with one exception6, prior BVS trials excluded patients with complex lesion characteristics, and follow-up in all previous trials with BVS was limited to 5 years, while resorption of a BVS is only complete between 3 and 4 years after implantation. Therefore, in the COMPARE-ABSORB trial, we hypothesised that the use of a BVS in a high-risk population for restenosis, when using a specific BVS implantation protocol, might demonstrate better long-term outcomes, compared with an everolimus-eluting stent (EES), after full BVS resorption with a follow-up of 7 years. Spline analysis, demonstrating the hazard risk over time for BVS, based on the final 5-year results of the ABSORB programme, points in this direction10.

In this report, we present the final 7-year results from the COMPARE-ABSORB trial.

Methods

The study design has been previously published11. In summary, the COMPARE-ABSORB trial is a prospective, randomised, controlled, single-blind, multicentre study across 45 centres in Europe (Supplementary Table 1). Patients aged 18-75 years with symptomatic ischaemic heart disease and presence of high-risk features for restenosis due to clinical profile or coronary lesion complexity and who were scheduled to undergo elective or emergent PCI were eligible. Subjects participating in the trial met at least one of the inclusion criteria: medically treated diabetes, multivessel disease with more than one de novo target lesion, and/or presence of at least one complex target lesion (long lesion, small vessel, total occlusion, or bifurcation). Key exclusion criteria included a target lesion not suitable for BVS implantation, patients with cardiogenic shock, severe renal failure, a severely impaired ejection fraction, left main disease, or those on oral anticoagulants. Detailed criteria are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive either a BVS (Absorb [Abbott]) or an EES (XIENCE [Abbott]). Blocked randomisation was performed with randomly selected block sizes. A dedicated implantation technique was defined in the protocol: predilatation using non-compliant balloons of the same diameter as the reference vessel diameter (RVD) and post-scaffold high-pressure (≥16 atm) dilatation were mandatory in the BVS group. Scaffold-to-vessel sizing was based on the instructions for use. The primary endpoint was TLF (a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction [TVMI] and clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation [CI-TLR]). The primary objective was to show non-inferiority of BVS compared with EES at 1 year, and the co-primary objective was to show superiority of BVS compared with EES at 7-year follow-up subsequent to landmark analysis at 3 years. An additional, non-powered objective is to show superiority of BVS compared with EES up to 7-year follow-up. An extended methods section is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1, including study organisation, hypotheses, sample size calculation, endpoints, and the definition of clinically indicated target vessel and lesion revascularisation. Follow-up is up to 7 years after randomisation.

Invasive imaging was planned in a prespecified subpopulation of 62 diabetic patients at selected sites. At the index procedure, the patients underwent intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging pre- and post-procedure. Angiography and IVUS were repeated at 62 months of follow-up. The main objective of the substudy was to assess in diabetic patients with complex coronary artery disease the performance of the BVS compared with the EES in terms of plaque regression in the stented/scaffolded segment (percentage change in total atheroma volume) at 62 months.

Statistical analysis

All clinical data were analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle.

For time-to-event endpoints, hazard ratios (HRs) and Kaplan-Meier plots were constructed and compared by the log-rank test. Percentages shown in tables and graphs of time-to-event analyses are Kaplan-Meier estimates. For landmark analysis, patients with the event of interest before the landmark were excluded from the analysis after the landmark, as were patients who were censored before the landmark.

To further examine the change in hazard ratio during the 7-year follow-up period, a flexible parametric survival model – restricted cubic spline analysis – was used to estimate the HR and its 95% confidence interval (CI) of TLF over time. Five knots were selected at clinically relevant points of 30 days, and 3, 4, 5, and 6 years post-randomisation. To show that the choice of knots did not affect the results, we ran a test with automated knot placement, based on equal numbers of outcome events in the intervals between the knots. The SAS macro (SAS Institute) we created for this was based on a macro by Austin et al12.

Forest plots for subgroups were created, and a p-value for interaction was calculated.

Dichotomous variables were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test, ordinal variables with >2 categories were evaluated by the Mantel-Haenszel rank score test, and categorical variables with >2 categories were evaluated by the chi-square test. Continuous variables were tested with a two-sample t-test or with the Mann-Whitney U test when data were not normally distributed.

A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02486068.

Results

Baseline patient, lesion, and procedural characteristics and 1-year results

Between 28 September 2015 and 31 August 2017, 1,670 (80%) of the intended 2,100 patients were randomly assigned to receive either a BVS (848 patients with 1,243 lesions) or an EES (822 patients with 1,214 lesions). Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Of the 1,670 patients, 293 (34.6%) in the BVS group and 296 (36.1%) in the EES group had a history of diabetes, and 442 (52.1%) in the BVS group and 400 (48.7%) in the EES group presented with an acute coronary syndrome, including acute non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI) and STEMI patients. According to the implantation protocol for BVS, predilatation was performed in 96.5% of lesions and post-dilatation in 92.8% of lesions treated with BVS – significantly higher compared with the EES group.

Although enrolment was prematurely stopped on the recommendation of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board based on significantly more device thrombosis and target vessel myocardial infarction in the BVS arm than the EES arm, the primary endpoint of non-inferiority for TLF at 1-year follow-up was nevertheless met with statistical significance (pnon-inferiority<0.001)7.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | BVS (n=848) | EES (n=822) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient measures | |||

| Age, years | 62 [56; 69] | 63 [56; 69] | 0.61 |

| Male | 674/848 (79.5) | 627/822 (76.3) | 0.13 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27 [25; 31] | 27 [25; 30] | 0.43 |

| Current smoker | 241/837 (28.8) | 217/807 (26.9) | 0.41 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 293/846 (34.6) | 296/821 (36.1) | 0.57 |

| Hypertension | 601/839 (71.6) | 567/819 (69.2) | 0.31 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 546/824 (66.3) | 531/807 (65.8) | 0.88 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 278/767 (36.2) | 241/760 (31.7) | 0.07 |

| Previous MI | 154/847 (18.2) | 166/820 (20.2) | 0.29 |

| Established peripheral vascular disease | 59/842 (7.0) | 56/819 (6.8) | 0.92 |

| Previous PCI | 229/847 (27.0) | 238/822 (29.0) | 0.38 |

| Previous CABG | 16/848 (1.9) | 21/822 (2.6) | 0.41 |

| Previous stroke | 29/845 (3.4) | 39/820 (4.8) | 0.18 |

| Renal insufficiencya | 33/845 (3.9) | 49/817 (6.0) | 0.054 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.84 | ||

| Good (>60%) | 492/661 (74.4) | 486/647 (75.1) | |

| Reduced (30-60%) | 155/661 (23.4) | 143/647 (22.1) | |

| Poor (<30%) | 14/661 (2.1) | 18/647 (2.8) | |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Stable coronary artery disease | 406/848 (47.9) | 422/822 (51.3) | 0.17 |

| Silent ischaemia | 63/848 (7.4) | 73/822 (8.9) | |

| Stable angina | 343/848 (40.4) | 349/822 (42.5) | |

| ACS | 442/848 (52.1) | 400/822 (48.7) | 0.17 |

| Unstable angina | 149/848 (17.6) | 141/822 (17.2) | |

| Non-ST-segment elevation MI | 183/848 (21.6) | 156/822 (19.0) | |

| ST-segment elevation MI | 110/848 (12.9) | 103/822 (12.5) | |

| Data are median [interquartile range] or n/N (percentage). aRenal insufficiency is defined as an MDRD estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m² or serum creatinine above 130 micromol/L. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention | |||

Table 2. Angiographic and procedural characteristics.

| BVS (n=1,243 lesions) | EES (n=1,214 lesions) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| Number of target lesions undergoing treatment attempt per patient | 1 [1; 2] (n=848) | 1 [1; 2] (n=822) | 0.64 |

| Multivessel treatment | 441/848 (52.0) | 433/822 (52.7) | 0.81 |

| IVUS performed post-procedure | 126/848 (14.9) | 122/822 (14.8) | 1.00 |

| OCT performed post-procedure | 84/848 (9.9) | 24/822 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Target lesion measures | |||

| Lesion location | 0.11 | ||

| LAD | 569/1,243 (45.8) | 503/1,214 (41.4) | |

| LCx | 281/1,243 (22.6) | 310/1,214 (25.5) | |

| RCA | 392/1,243 (31.5) | 400/1,214 (32.9) | |

| Left main | 1/1,243 (0.1) | 1/1,214 (0.1) | |

| Bifurcation lesions | 254/1,243 (20.4) | 269/1,214 (22.2) | 0.30 |

| Two or more devices used in bifurcation lesions | 82/254 (32.3) | 68/269 (25.3) | 0.08 |

| Pre-existing total occlusions | 181/1,243 (14.6) | 159/1,214 (13.1) | 0.32 |

| Long lesions (>28 mm) | 312/1,243 (25.1) | 382/1,214 (31.5) | <0.001 |

| Small vessel lesions (>2.25 mm, ≤2.75 mm) | 302/1,243 (24.3) | 404/1,214 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| SYNTAX score | 11 [7;17] | 11 [7;16] | 0.88 |

| Number of study devices implanted per lesion | 1 [1; 2] | 1 [1;1] | 0.06 |

| Median total device length per lesion, mm | 28 [18; 36] | 28 [18; 38] | 0.29 |

| Median device diameter per lesion, mm | 3.0 [2.8; 3.5] | 3.0 [2.8; 3.5] | <0.001 |

| Overlapping devices implantation | 194/1,243 (15.6) | 256/1,214 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Lesions without study device | 44/1,243 (3.5) | 9/1,214 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Predilatation | 1,199/1,243 (96.5) | 954/1,214 (78.6) | <0.001 |

| Largest balloon, mm | 3.0 [2.5; 3.0] | 3.0 [2.5; 3.0] | 0.95 |

| Non-compliant balloon used | 815/1,199 (68.0) | 504/954 (52.8) | <0.001 |

| Maximum pressure used, atm | 16 [12; 18] | 14 [12; 16] | 0.002 |

| Cutting/scoring balloon used | 72/1,243 (5.8) | 28/1,214 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Post-dilatation | 1,113/1,199 (92.8) | 699/1,205 (58.0) | <0.001 |

| Largest balloon, mm | 3.5 [3.0; 3.5] | 3.5 [3.0; 3.5] | 0.53 |

| Non-compliant balloon used | 1,039/1,199 (86.7) | 616/1,205 (51.1) | <0.001 |

| Maximum pressure used, atm | 18 [16; 20] | 18 [16; 20] | 0.80 |

| Maximum pressure ≥16 atm | 899/1,113 (80.8) | 561/699 (80.3) | 0.81 |

| Procedure success | 749/848 (88.3) | 772/820 (94.1) | <0.001 |

| TIMI flow post-procedure | 0.80 | ||

| 0 | 2/1,243 (0.2) | 0/1,214 (0) | |

| 1 | 2/1,243 (0.2) | 1/1,214 (0.1) | |

| 2 | 8/1,243 (0.6) | 12/1,214 (1.0) | |

| 3 | 1,231/1,243 (99.0) | 1,201/1,214 (98.9) | |

| Angiographic analysis (core laboratory) | |||

| Preprocedure | |||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 2.51±0.50 (1,123) | 2.49±0.49 (1,109) | 0.21 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 0.89±0.49 (1,148) | 0.89±0.50 (1,129) | 0.74 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 64.3±18.4 (1,148) | 63.7±18.7 (1,129) | 0.41 |

| Lesion lengtha, mm | 12.46±6.96 (986) | 12.46±6.96 (973) | 0.23 |

| Angiographic analysis (core laboratory) | |||

| Post-procedure | |||

| In-device measures | |||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 2.63±0.45 (1,161) | 2.66±0.42 (1,159) | 0.07 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 2.21±0.41 (1,161) | 2.32±0.39 (1,159) | <0.001 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 15.5±8.6 (1,161) | 12.10±6.44 (1,159) | <0.001 |

| Acute gain, mm | 1.33±0.57 (1,123) | 1.42±0.53 (1,111) | <0.001 |

| In-segment measures | |||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 2.55±0.46 (1,161) | 2.57±0.44 (1,159) | 0.38 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 2.01±0.42 (1,161) | 2.02±0.44 (1,159) | 0.61 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 21.0±9.7 (1,161) | 21.3±10.3 (1,159) | 0.52 |

| Acute gain, mm | 1.13±0.56 (1,123) | 1.13±0.55 (1,111) | 0.98 |

| Data are median [interquartile range], mean±standard deviation (count), or n/N (percentage). aST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and chronic total occlusion lesions were excluded. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; LAD: left anterior descending artery; LCx: left circumflex artery; OCT: optical coherence tomography; OIT: optimal implantation technique; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; QCA: quantitative coronary analysis; RCA: right coronary artery; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction | |||

Clinical outcomes at 7-year follow-up after a 3-year landmark analysis

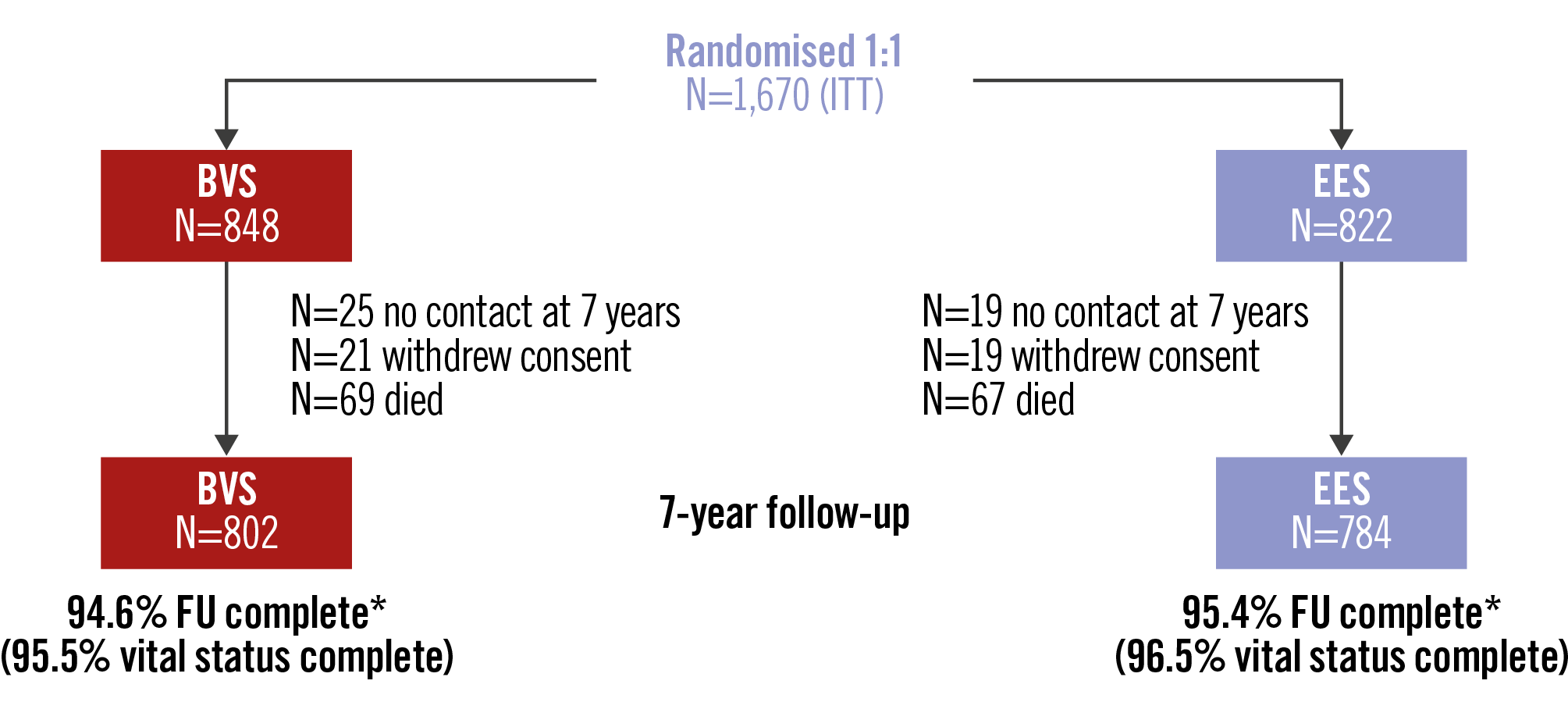

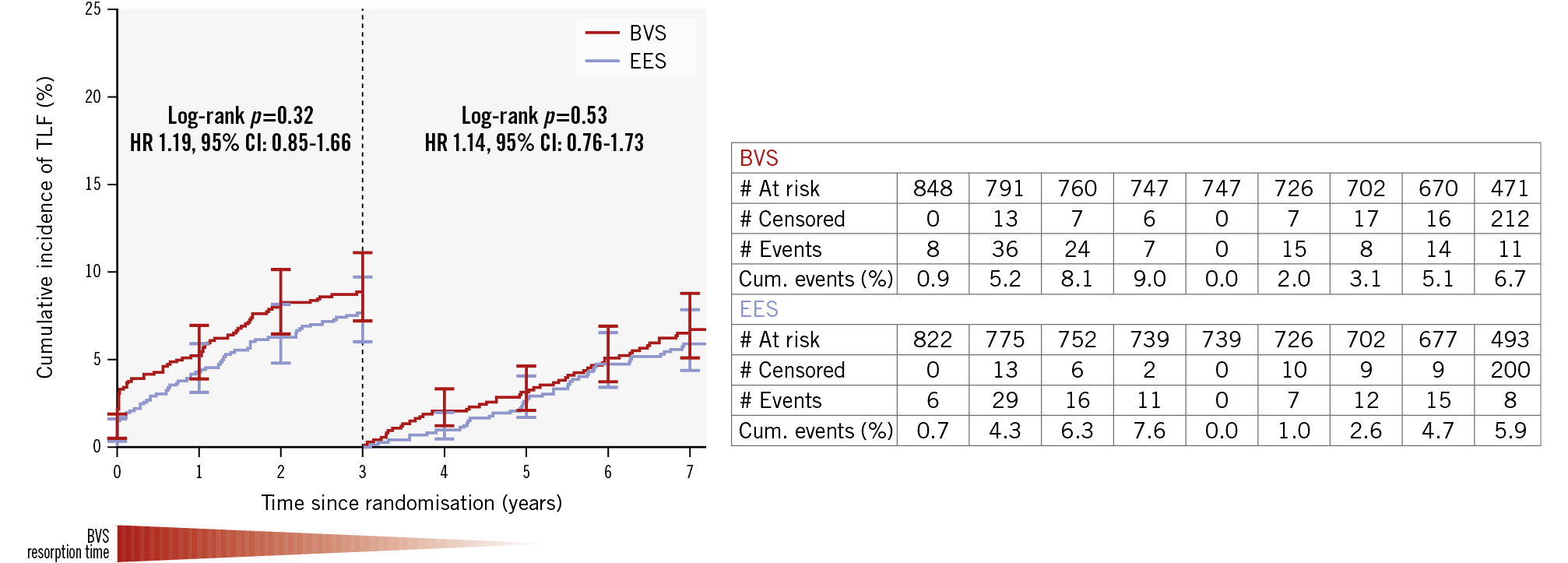

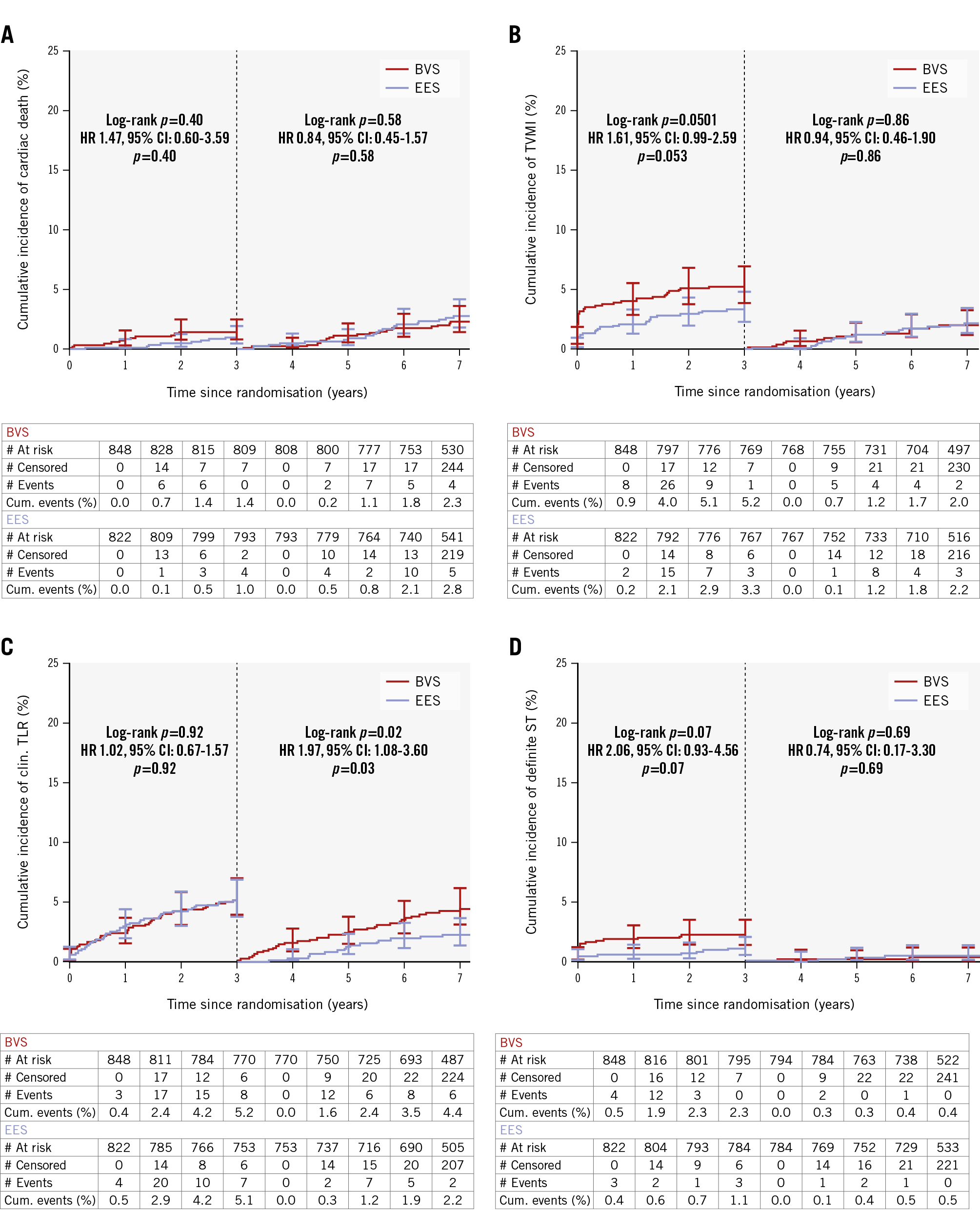

Clinical follow-up at 7 years was complete in 802/848 (94.6%) patients treated with BVS versus 784/822 (95.4%) patients in the EES group (Figure 1). Vital status could be obtained in 17 of the 44 patients lost to follow-up, resulting in 7-year vital status of 95.5% in the BVS arm and 96.5% in the EES arm. The clinical outcomes at 7 years after a 3-year landmark analysis are shown in Table 3. The co-primary objective, TLF between 3 and 7 years, based on a 3-year landmark analysis, showed no difference between BVS and EES: 6.7% versus 5.9%, respectively; HR 1.14, 95% CI: 0.76-1.73; p=0.53 (Figure 2). Cardiac death and TVMI rates between BVS and EES were not different at 2.3% (n=18) versus 2.8% (n=21); HR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.45-1.57; p=0.58, and 2.0% (n=15) versus 2.2% (n=16); HR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.46-1.90; p=0.86, respectively. However, the rate of CI-TLR was significantly higher for BVS compared with EES (4.4% vs 2.2%; HR 1.97, 95% CI: 1.08-3.60; p=0.023). Device thrombosis rates were not different: 0.4% versus 0.5% for BVS and EES, respectively (HR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.17-3.30; p=0.69) (Table 3, Figure 3A-Figure 3B-Figure 3C-Figure 3D).

Figure 1. Seven-year study flowchart. *Complete clinical information available. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; FU: follow-up; ITT: intention-to-treat

Table 3. Clinical outcomes at 3-year follow-up, at 7-year follow-up after 3-year landmark analysis, and at 7-year follow-up.

| 0-3 years | 3-7 years | 0-7 years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BVS, % | EES, % | HR (95% CI) | PLR | BVS, % | EES, % | HR (95% CI) | PLR | BVS, % | EES, % | HR (95% CI) | PLR | |

| TLF | 9.0 | 7.6 | 1.19 (0.85-1.66) | 0.32 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 1.14 (0.76-1.73) | 0.53 | 15.1 | 13.1 | 1.17 (0.90-1.52) | 0.24 |

| TVF | 10.7 | 8.8 | 1.25 (0.92-1.71) | 0.16 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 1.11 (0.75-1.64) | 0.60 | 17.5 | 14.9 | 1.19 (0.94-1.52) | 0.15 |

| Death, all-cause | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.09 (0.57-2.05) | 0.80 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 0.96 (0.64-1.43) | 0.83 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 0.99 (0.71-1.39) | 0.96 |

| Cardiac death | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.47 (0.60-3.59) | 0.40 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 0.84 (0.45-1.57) | 0.58 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 1.01 (0.61-1.69) | 0.96 |

| MI | 6.0 | 4.3 | 1.41 (0.91-2.17) | 0.12 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 0.89 (0.52-1.51) | 0.67 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 1.17 (0.84-1.64) | 0.34 |

| TVMI | 5.2 | 3.3 | 1.61 (0.99-2.59) | 0.0501 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.94 (0.46-1.90) | 0.86 | 7.2 | 5.4 | 1.36 (0.92-2.01) | 0.13 |

| All revascularisations | 12.4 | 12.5 | 0.99 (0.76-1.31) | 0.97 | 9.4 | 7.9 | 1.18 (0.82-1.70) | 0.36 | 20.6 | 19.4 | 1.06 (0.85-1.32) | 0.60 |

| TV revascularisations | 8.6 | 8.0 | 1.08 (0.78-1.52) | 0.63 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 1.49 (0.94-2.36) | 0.089 | 14.4 | 12.0 | 1.21 (0.92-1.59) | 0.16 |

| TL revascularisations | 6.8 | 6.4 | 1.07 (0.74-1.56) | 0.71 | 4.7 | 2.5 | 1.87 (1.06-3.31) | 0.0288 | 11.2 | 8.8 | 1.28 (0.94-1.75) | 0.12 |

| Clinically indicated TV revascularisations | 7.0 | 6.7 | 1.05 (0.72-1.52) | 0.81 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 1.31 (0.82-2.11) | 0.26 | 12.2 | 10.6 | 1.14 (0.85-1.53) | 0.37 |

| Clinically indicated TL revascularisations | 5.2 | 5.1 | 1.02 (0.67-1.57) | 0.92 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 1.97 (1.08-3.60) | 0.0236 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 1.29 (0.91-1.82) | 0.15 |

| Definite device thrombosis | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.06 (0.93-4.56) | 0.067 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.74 (0.17-3.30) | 0.69 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.66 (0.83-3.29) | 0.14 |

| Definite and probable device thrombosis | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.17 (0.99-4.77) | 0.047 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.74 (0.17-3.30) | 0.69 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.73 (0.88-3.42) | 0.11 |

| BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; CI: confidence interval; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; MI: myocardial infarction; PLR: log-rank p; TL: target lesion; TLF: target lesion failure; TV: target vessel; TVF: target vessel failure; TVMI: target vessel myocardial infarction | ||||||||||||

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier plot for the co-primary endpoint, TLF, at 7-year follow-up after a 3-year landmark analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves show the cumulative incidence of target lesion failure. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; CI: confidence interval; cum: cumulative; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; TLF: target lesion failure

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier plots for the individual components of the co-primary endpoint and definite device thrombosis. A) Cardiac death; (B) target vessel myocardial infarction; (C) clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation; (D) definite device thrombosis. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; CI: confidence interval; clin.: clinically indicated; cum: cumulative; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; ST: stent thrombosis; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVMI: target vessel myocardial infarction

Clinical outcomes up to 7-year follow-up

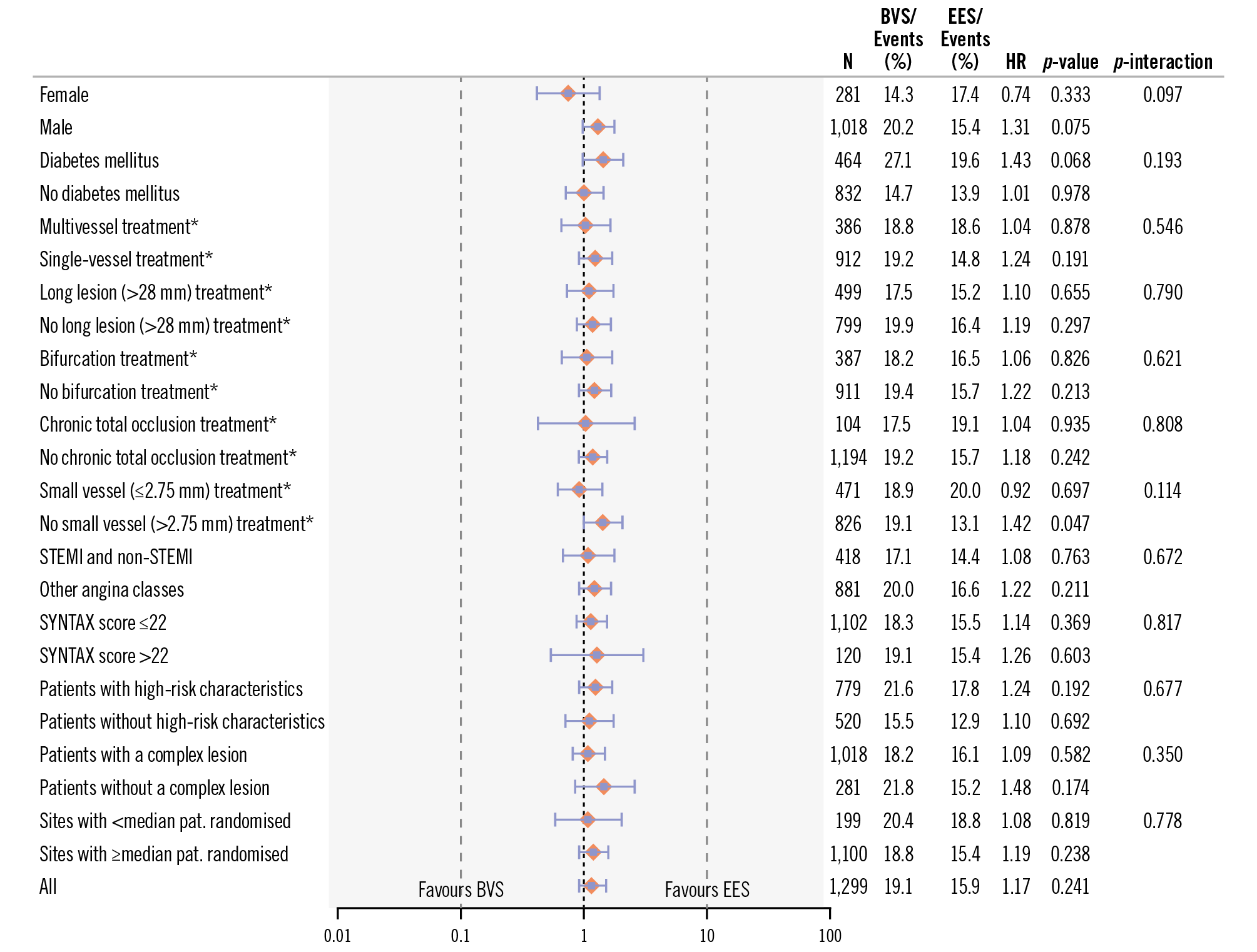

Annual clinical outcomes at 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7 years are given in Supplementary Table 3. The primary endpoint of TLF at 7 years occurred in 123 patients (15.1%) in the BVS group and in 104 patients (13.1%) in the EES group; this was not statistically significant (HR 1.17, 95% CI: 0.90-1.52; p=0.24) (Table 3, Central illustration, Supplementary Figure 1). Cardiac death, TVMI, CI-TLR, and definite device thrombosis rates were also not statistically different (Table 3, Supplementary Figure 2A-Supplementary Figure 2B-Supplementary Figure 2C-Supplementary Figure 2D). Subgroup analysis showed consistency of the TLF outcomes with BVS and EES across all predefined subgroups (Figure 4).

Landmark analyses at 30 days or 1 year showed no differences between BVS and EES in any clinical outcome parameter at 7-year follow-up. In fact, the time-to-event curves run parallel up to 7 years after the initial 30 days, except for CI-TLR. After 3-year follow-up, the CI-TLR curves started to diverge, with an increase in revascularisations of BVS-treated lesions (Supplementary Figure 3A-Supplementary Figure 3B-Supplementary Figure 3C-Supplementary Figure 3D).

Dual antiplatelet treatment (DAPT) and cardiac medication up to 7-year follow-up are provided in Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Figure 4. Between 4 and 7 years of follow-up, DAPT usage was similar between both arms.

Central illustration. BVS versus EES in patients at high risk for restenosis: final 7-year outcomes of the COMPARE-ABSORB trial. COMPARE-ABSORB is a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing BVS versus EES in 1,670 patients at high risk for coronary restenosis. A Kaplan-Meier plot shows the primary endpoint, TLF (defined as the combined clinical outcome of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation), from the index procedure to 7-year follow-up. No benefit in TLF was observed with BVS in the very long term, even in a 3-year landmark analysis (co-primary analysis). In the 3-year landmark analysis, more target lesion revascularisation occurred with BVS compared with EES between 3- and 7-year follow-ups. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; CI: confidence interval; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TLF: target lesion failure

Figure 4. Stratified analyses of the co-primary endpoint across subgroups. Hazard ratio with 95% CI and p-value results were from Cox proportional hazards analysis. *Analysis based on patients with at least one target lesion within the subgroup characteristics. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; N: number of patients; pat.: patients; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Case description of scaffold thrombosis between 3 and 7 years

Three patients in the BVS arm experienced a scaffold thrombosis between 3- and 7-year follow-ups. One patient was treated with a BVS in the mid-left anterior descending artery (LAD; BVS 3.5x18 mm, postdilatated with a 4.0 mm non-compliant balloon) and mid-ramus circumflex (RCx; BVS 3.0x28 mm, postdilatated with a 3.5 mm non-compliant balloon). On day 1,115, nine days after stopping clopidogrel (single antiplatelet therapy in combination with non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants), the patient was admitted with a non-STEMI and underwent coronary angiography and optical coherence tomography. The presence of thrombus at the LAD scaffold remnants with a 56% diameter stenosis by quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) was observed. The second patient was treated in the mid-LAD with a 2.5x12 mm BVS, with post-dilatation performed using a 2.5 mm non-compliant balloon. On day 1,304, the patient was admitted with STEMI while on monotherapy with acetylsalicylic acid. Coronary angiography showed occlusion of the LAD with thrombus in the scaffold segment. The third patient was treated for tandem lesions in the proximal and mid-RCx with adjacently implanted 3.5x28 mm and 3.0x18 mm BVS, with post-dilatation performed using a 3.5 mm non-compliant balloon at 16 atmospheres. On day 2,174, the patient was admitted for myocardial infarction, which, according to the investigator, was a thrombotic-appearing occlusion and was treated by angiography of the mid-RCx. Although no electrocardiogram or biomarkers were available, the clinical event adjudication committee judged the patient to have myocardial infarction and scaffold thrombosis on clinical grounds.

Hazard risk evolution up to 7-year follow-up

Spline analysis demonstrating the hazard ratio for TLF over time for BVS in comparison to EES is presented in Supplementary Figure 5, showing an increase in the HR between years 3 and 4, followed by a decrease between years 4 and 5, similar to what has been previously described10. However, a subsequent increase was seen between 5- and 7-year follow-ups.

Angiographic diabetic substudy

In the end, 15 of the intended 62 diabetic patients were enrolled in the angiographic substudy, and only 9 of these 15 patients (5 in the BVS arm and 4 in the EES arm) underwent elective coronary angiography and IVUS at 62-month follow-up.

Discussion

The COMPARE-ABSORB trial is unique in the sense that (1) it is the only randomised controlled trial that evaluates the outcomes of BVS beyond the 5-year follow-up, when the scaffold is fully absorbed and the treated segment has been completely uncaged for a few years, and that (2) it is the only trial that implemented a dedicated implantation protocol for BVS from the start13.

In this final 7-year follow-up, we report that BVS did not show any benefit compared with EES. Moreover, the treatment effect on TLF was similar across different subgroups, including risk groups defined according to lesion complexity or baseline characteristics. The co-primary endpoint of TLF at 7 years following a 3-year landmark analysis did not meet superiority for BVS compared with EES. In fact, at between 3 and 4 years, target vessel and lesion revascularisations curves started to diverge because of increases in both outcomes in the BVS arm. The cause of this late uptake in revascularisations is unknown. However, it is known that scaffold remnants are still visible at 3 years by optical coherence tomography1415 and that dismantling of the scaffold potentially might have altered flow patterns and caused new stenoses to form between 3- and 4-year follow-ups. Alternatively, resorption of polylactic acid might have caused an intramural acidic milieu and a trigger for late neoatherosclerosis.

In COMPARE-ABSORB, ischaemic events such as scaffold thrombosis and target vessel myocardial infarction in the BVS arm predominantly occurred during the early phase after implantation, implicating procedure-related causes. After the initial 30 days, the ischaemic event curves for BVS and EES, including TLF, were superimposed up to 7 years of follow-up, suggesting non-inferiority (Central illustration). This finding differs from the ABSORB programme and the AIDA trial610, both of which reported an excess of ischaemic events with BVS up to 3-4 years, after which the event rates converged with those of EES. The findings in our trial are likely related to the optimal implantation techniques applied from the onset and patient selection.

Regarding the early increase in ischaemic risk with BVS, likely attributable to procedural causes, a post hoc angiographic analysis performed by the core lab showed that 40.9% of lesions in the BVS group had a postprocedural RVD smaller than 2.5 mm7.

These findings emphasise the importance of appropriate vessel sizing, which cannot be truly achieved by visual assessment alone nor by QCA as it structurally underestimates the vessel size16. Mandatory intravascular imaging guidance should be explored in future when implanting BVS to enhance safety. Furthermore, correct sizing with BVS according to the sizing criteria is difficult to achieve in the majority of lesions with one BVS because of a mismatch in size between the proximal and distal reference diameters and the expansion limits of BVS7. In the COMPARE-ABSORB trial, high-pressure post-dilatation with a non-compliant balloon was mandated by protocol. Nevertheless, based on angiographic analysis, in-device acute gain and established postprocedural minimal lumen diameter in the BVS arm did not match those in the EES arm, although the absolute differences between both arms appear to be smaller than or similar to the differences observed in previous trials7. This unclosed gap in acute performance between both devices could also be a contributing factor for early scaffold thrombosis with BVS compared with EES. Further improvements to the device, such as thinner and smaller struts, better conformability, and radial strength, are therefore indispensable.

Late scaffold thrombosis occurred at similar rates for BVS compared with EES between 3- and 7-year follow-ups and even between 30-day and 7-year follow-ups. Between 3 and 7 years, three definite scaffold thromboses occurred. Two cases occurred between 3 and 4 years, which probably was related to the resorption and dismantling process, and one case occurred around 6 years of follow-up, potentially related to neoatherosclerosis.

Compared with the 5-year results of the ABSORB IV trial5, the definite scaffold thrombosis rate was slightly higher in the present study at 5-year follow-up (2.5% vs 1.7%), whilst it was similar in the EES group (1.5% vs 1.1%). The observed higher device thrombosis rate in this trial can likely be attributed to the higher complexity of patients and lesions included in the COMPARE-ABSORB trial. Chronic total occlusions, acute coronary syndrome patients (including STEMI patients), bifurcations and very long lesions were included in this trial, whereas they were excluded from ABSORB IV5. On the other hand, in the ABSORB IV trial, the TLF rates in both (BVS and EES) groups were approximately an absolute 5% higher at 5 years compared with COMPARE-ABSORB. This is highly likely related to the different myocardial infarction endpoint definitions between both protocols and to the different clinically indicated lesion revascularisation rates between the European sites (COMPARE-ABSORB) and the sites predominantly in the United States (ABSORB IV).

In comparison to the 5-year outcome results from the all-comer AIDA trial6, COMPARE-ABSORB has a lower scaffold thrombosis rate (2.5% vs 4.1%, respectively) and a lower TLF rate (11.8% vs 14.9%, respectively). However, in the EES arm, stent thrombosis rates were similar (1.5% vs 1.0%, respectively), while the TLF rates were lower (10.1% vs 13.7%, respectively). The latter might be explained by the dedicated implantation technique that was implemented from the start in COMPARE-ABSORB and by the all-comer inclusion concept of AIDA.

One of the promises of absorbable scaffolds is the prevention of very late adverse events once the scaffold is fully resorbed and the vessel has been uncaged, thereby restoring pulsatility, vasomotion, and remodelling. However, this effect was not observed in the current 7-year COMPARE-ABSORB trial nor in the 5-year follow-up studies from other trials (ABSORB II, III, IV, AIDA, and ABSORB Japan)45610. A possible explanation is the relatively long complete resorption time of 3 to 4 years with BVS, which may delay the manifestation of late benefits. Nevertheless, extending the follow-up to 7 years in our study failed to demonstrate such an effect.

That said, other important advantages of a “metal-free” vessel may emerge over time, such as greater ease of reintervention, improved access to side branches, or the possibility of grafting a previously treated segment. It is well established that in cases of metallic stent restenosis, a stent-in-stent procedure with multiple stent layers increases procedural complexity and carries a higher risk of adverse events17. Similarly, fenestration of side branches by a metallic stent permanently hampers access and complicates side branch interventions. In contrast, bioresorbable scaffolds have been shown to uncage the side branch and enlarge the area of side branch ostia after resorption, thereby facilitating access181920. Finally, bypass grafts cannot be placed on previously metallic stented segments – an issue that disappears when bioresorbable scaffolds are used. In our trial, we identified seven cases in the BVS arm that required bypass grafting at between 3 and 7 years of follow-up. Of these, one case involved grafting of the target vessel at the segment previously treated with a BVS.

Other therapies like drug-coated balloons, other bioresorbable scaffolds with thinner struts or a magnesium alloy (Freesolve [Biotronik]), or a hybrid DES (DynamX [Elixir Medical]) might provide a better clinical advantage over permanent metallic DES in the long term. On the other hand, it might also be the case that beyond an early phase, the natural progression of atherosclerosis is the main cause of future events in the long term, irrespective of the initial device therapy.

Limitations

First of all, despite the fact that an optimal implantation protocol was incorporated in the study design, optimal sizing and post-procedure control with mandatory use of intravascular imaging were not implemented. The low rate of intravascular imaging in this trial could have influenced the results. Secondly, a significantly prolonged DAPT regimen in the BVS arm compared with the EES arm potentially might have masked an increase in myocardial infarction and scaffold thrombosis rates in the BVS arm up to 4-year follow-up. Thirdly, as the trial was not double-blinded, we cannot rule out selection bias on reangiography and reinterventions. Fourthly, the enrolment was terminated at 80% of the required sample size of 2,100 patients; this resulted in lower than 90% power for the second primary hypothesis. Lastly, the study results only apply to the BVS, which is no longer commercially available for use in clinical practice. Nevertheless, the COMPARE-ABSORB study is the first trial to investigate the concept of preventing adverse events in the very long term (7 years) with a bioresorbable scaffold.

Conclusions

In the present large-scale randomised trial of patients at high risk of restenosis with a dedicated implantation protocol, BVS did not show superiority compared with metallic DES in the very long term.

Impact on daily practice

This trial showed no benefit in the very long term of using an optimal implantation technique and prolonging dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 1 year following bioresorbable vascular scaffold implantation. Other devices and treatment strategies are needed to improve the long-term outcome of percutaneous coronary intervention in patients at high risk for restenosis.

Acknowledgements

All authors are indebted to Mrs Ute Windhovel (CERC, Massy, France), Mrs Ria van Vliet (Maasstad CardioResearch, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), Mrs Monique Schuijer, and Jacintha Ronden (both Cardialysis, Rotterdam, the Netherlands) for their assistance in coordinating the trial.

Funding

The trial sponsor was Maasstad Hospital, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, which received an institutional grant from Abbott Vascular. The grant-giver was not involved in the conduction, data management, or data analysis of the trial. The trial was conducted by CERIC, Geneva, Switzerland, which contracted CERC and Cardialysis as CRO and core lab, respectively.

Conflict of interest statement

P.C. Smits received institutional research grants and consultancy fees from Abbott, Sahajand Medical Technologies (SMT), and Terumo; received speaker fees from Elixir Medical and MicroPort; and is a minor shareholder of CERC. B. Chevalier received grants and personal fees from Abbott during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Medtronic, Terumo, and Biotronik, outside the submitted work; and is a minor shareholder of CERC. N.E.J. West has received speaker fees from and was previously an employee of Abbott. T. Gori received speaker fees from Abbott. E. Barbato received personal fees from Boston Scientific, Abbott, OpSens Medical, and GE HealthCare, outside the submitted work. V. Kočka received personal fees from Abbott, Medtronic, B. Braun, and Terumo, outside the submitted work. J.G.P. Tijssen received grants and personal fees from Abbott during the conduct of the study. M.-C. Morice is the CEO of CERC, the CRO who conducted the trial. Y. Onuma was an advisory board member of Abbott. R.-J. van Geuns reports consulting and speaker fees from Abbott and AstraZeneca; and received institutional research grants from Amgen, InfraRedx, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.