Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: Long-term outcomes following implantation of drug-eluting coronary stents are necessary to determine safety and efficacy.

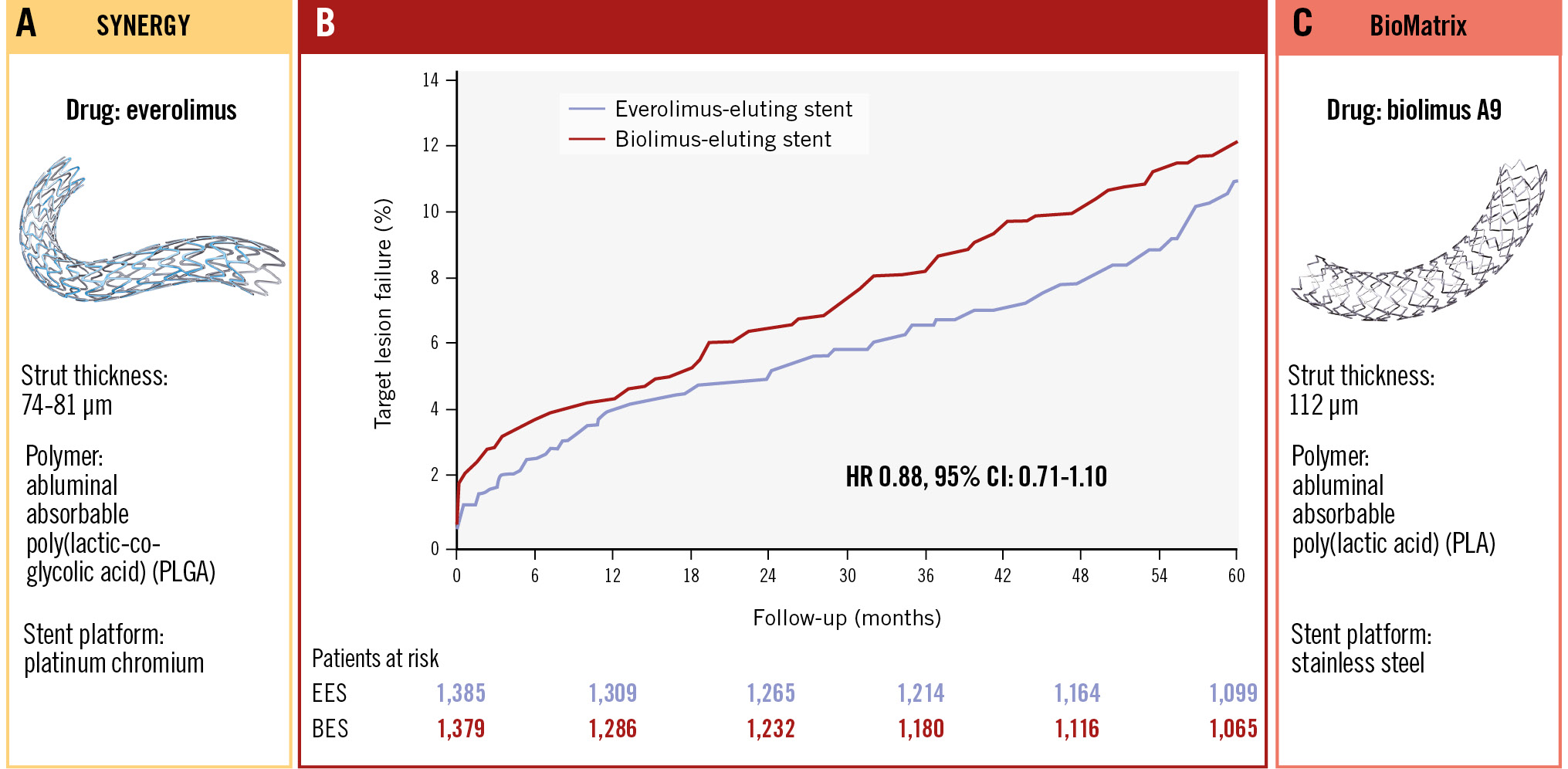

Aims: We aimed to report the 5-year outcomes of the SYNERGY thin-strut biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting platinum-chromium stent (EES) versus the BioMatrix NeoFlex biodegradable-polymer biolimus-eluting stainless-steel stent (BES).

Methods: This randomised, multicentre, all-comer, non-inferiority trial was undertaken at three sites in Western Denmark. Patients with a clinical indication for percutaneous coronary intervention were eligible for inclusion. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to either EES or BES. Outcomes included target lesion failure (TLF: cardiac death, myocardial infarction not clearly attributable to a non-target lesion, or target lesion revascularisation), all myocardial infarctions, and very late stent thrombosis at 5-year follow-up.

Results: We included 2,764 patients and randomly assigned 1,385 patients to treatment with EES and 1,379 patients to treatment with BES. TLF occurred in 150 patients (10.8%) assigned to the EES and in 165 (12.0%) assigned to the BES (rate ratio [RR] 0.88, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.71-1.10). The incidence of myocardial infarction was lower in the EES group (EES: n=85 [6.1%], BES: n=116 [8.4%]; RR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.54-0.95), while very late stent thrombosis was rare for both stent types (EES: n=12 [0.9%], BES: n=9 [0.7%]; RR 1.32, 95% CI: 0.56-3.14).

Conclusions: At 5-year follow-up, TLF was comparable for EES and BES. The incidence of myocardial infarction, however, was lower in patients randomised to EES versus BES implantation.

The development of the first drug-eluting stents (DES) revolutionised the field of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and initiated a series of optimisations and developments of new combinations of metal platforms, antiproliferative drugs and polymer coatings12345. While first-generation DES were associated with an increased risk of very late stent thrombosis (ST), most likely related to an inflammatory reaction caused by the applied polymers, newer-generation DES have improved long-term outcomes1267. One astute way of overcoming the issue of polymer-related interaction with the vessel wall involved the development of biodegradable polymers, rendering the stent surface more comparable to a bare metal stent once the drug of choice was eluted to the vessel wall and the polymer absorbed. Other attempts to reduce adverse events included reducing strut thickness by using cobalt-chromium or platinum-chromium alloys48910. Further, although all currently available DES utilise -limus drugs, the drugs differ, e.g., with regard to lipophilicity, and the choice of -limus drug may potentially influence outcomes.

The BioMatrix NeoFlex (Biosensors Interventional Technologies) and Nobori (Terumo) biolimus-eluting stents (BES) have been implanted in millions of patients worldwide, and these stents functioned as the test stent in SORT OUT V and as the comparator stent in SORT OUT VI, VII, and VIII81112. In SORT OUT VIII, we tested the SYNERGY (Boston Scientific) everolimus-eluting stent (EES), which utilises a thinner (74 to 81 μm) platinum-chromium platform and has faster polymer degradation compared to the BioMatrix NeoFlex. At 1-year follow-up, the EES was found to be non-inferior to the BES with respect to target lesion failure (TLF)12. The current analysis reports the long-term clinical outcomes of the two stent designs at 5-year follow-up.

Methods

Study design and patients

The study design was previously reported in the main results paper after 1 year12. Briefly, SORT OUT VIII is a randomised, multicentre, all-comer, two-arm, non-inferiority trial comparing two absorbable-polymer DES, the SYNERGY EES stent and the BioMatrix NeoFlex BES, in treating coronary artery and vein graft lesions. The EES elutes its drug within 3 months from a 4 μm biodegradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) coating that is located on the abluminal side of 74 μm (for stent sizes ≤2.5 mm), 79 μm (for 3.0 to 3.5 mm), or 81 μm (for 4.0 mm) platinum-chromium stents and is absorbed within 4 months. The stent was available with stent diameters of 2.25 mm to 4.00 mm and lengths of 8 mm to 38 mm. The BES elutes its drug within 30 days from an 8 μm biodegradable polylactide acid polymer (polylactide acid and a poly[D, L-lactide-co-glycolide]) coating that is located on the abluminal side of a 112 μm stainless-steel stent and is absorbed within 6 to 9 months. This stent was available with stent diameters of 2.25 mm to 4.00 mm and lengths of 8 mm to 36 mm. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were ≥18 years old, (2) had chronic stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndrome, and (3) had at least one coronary lesion with >50% diameter stenosis, a reference diameter of at least 2.25 mm, and required PCI treatment and implantation of a DES. The allocated study stent had to be used in all DES-treatable lesions when multiple lesions were treated, unless deemed unsuitable for stenting. Exclusion criteria were (1) allergy to aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, prasugrel, everolimus or biolimus; (2) participation in another randomised stent trial; (3) inability to provide written informed consent; or (4) life expectancy of <1 year.

The study complied with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (reference number 1-10-72-3-14). All patients provided written informed consent for trial participation. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02093845.

Randomisation

Patients were enrolled by the investigators and randomly allocated to treatment groups after diagnostic coronary angiography and prior to PCI. Permuted block randomisation by centre was used to assign patients (1:1) to receive EES or BES treatment. The allocation sequence was computer generated using an internet-based randomisation system (TrialPartner [Aarhus University Hospital, Skejby, Denmark]) and stratified by sex and presence of diabetes.

Study procedures

The definitions of endpoints are available in the 1-year publication12. Before implantation, patients received at least 75 mg of aspirin and a loading dose of a P2Y12 platelet inhibitor (600 mg clopidogrel, 180 mg ticagrelor, or 60 mg prasugrel) orally, and unfractionated heparin intravenously (5,000-10,000 IU or 70-100 IU/kg). Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and/or bivalirudin were used at the operator’s discretion. Recommended postprocedural dual antiplatelet regimens were 75 mg aspirin daily, lifelong, and a P2Y12 platelet inhibitor: 75 mg clopidogrel once daily for 6 months in cases of chronic stable coronary artery disease; 90 mg ticagrelor twice daily or 5-10 mg prasugrel once daily for 12 months in cases of acute coronary syndrome.

The 5-year primary endpoint was TLF, a composite of safety (cardiac death and myocardial infarction [MI] not clearly attributable to a non-target lesion) and efficacy (clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation [TLR]) (Central illustration). Secondary endpoints were a patient-related composite endpoint, defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, any MI, and any clinically indicated revascularisation (target vessel revascularisation [TVR] and non-TVR); all-cause mortality; cardiac mortality; MI; clinically indicated TLR; clinically indicated TVR; and definite, probable, or possible ST.

Event detection was performed using population-based healthcare databases, as previously described, and was clinically driven to avoid study-induced interventions. An independent event committee reviewed all endpoints and source documents to adjudicate causes of death, reasons for hospital admission, and diagnosis of MI. Two dedicated PCI operators at each participating centre reviewed the coronary angiographies for the event committee to classify ST and TVR or TLR (either with PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting).

Central illustration. Target lesion failure at 5-year follow-up. A) SYNERGY stent. B) Time-to-event curves for the primary endpoint, defined as a composite of safety (cardiac death and myocardial infarction not clearly attributable to a non-target lesion) and efficacy (target lesion revascularisation) at 60 months. C) BioMatrix stent. BES: biolimus-eluting stent; CI: confidence interval; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio

Statistical analysis

The trial was powered for assessing non-inferiority of the EES compared with the BES with respect to TLF at 12 months12. Distributions of continuous variables between study groups were compared using the two-sample t-test (or Cochran’s Q test for cases of unequal variance) or the Mann-Whitney U test, depending on whether the data followed a normal distribution or not.

Stratified analyses on female versus male patients and patients with or without diabetes were performed within the two study groups. Distributions of categorical variables were analysed using the χ2 test. In analyses of every endpoint, follow-up continued until the date of an endpoint event, death, emigration, or 5 years after stent implantation, whichever came first. Survival curves displaying cumulative incidence rates were constructed based on time to events, accounting for the competing risk of death. Patients who received the BES were used as the reference group for the overall and subgroup analyses. Rate ratios for major adverse cardiac events at 5-year follow-up were calculated for prespecified patient subgroups (based on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics). The intention-to-treat principle was used in all analyses. Except for the non-inferiority testing of the primary endpoint, a two-sided p-value<0.05 was regarded as indicating statistical significance.

Role of the funding sources

This trial was initiated and driven solely by the investigators. The study was supported by unrestricted grants from Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA and Biosensors Interventional Technologies Pte, Singapore.

These companies had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report, and they had no access to the clinical trial database. No affiliation or sponsorship affected the design, conduction, analysis, preparation or approval of this manuscript. N.B. Støttrup and M. Maeng had full access to all the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

A total of 2,764 patients were allocated to treatment with the EES (1,385 patients) or the BES (1,379 patients). Complete follow-up was available for 99.9%, with only 4 patients censored because of emigration. A CONSORT diagram is available in the 1-year publication12.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1) and procedural characteristics (Table 2) in the two study groups were well balanced. The median age was 66 years, approximately 18% had diabetes, 20% had ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, approximately 54% had acute coronary syndromes, approximately 17% of lesions were bifurcations, and 34% of lesions were type C.

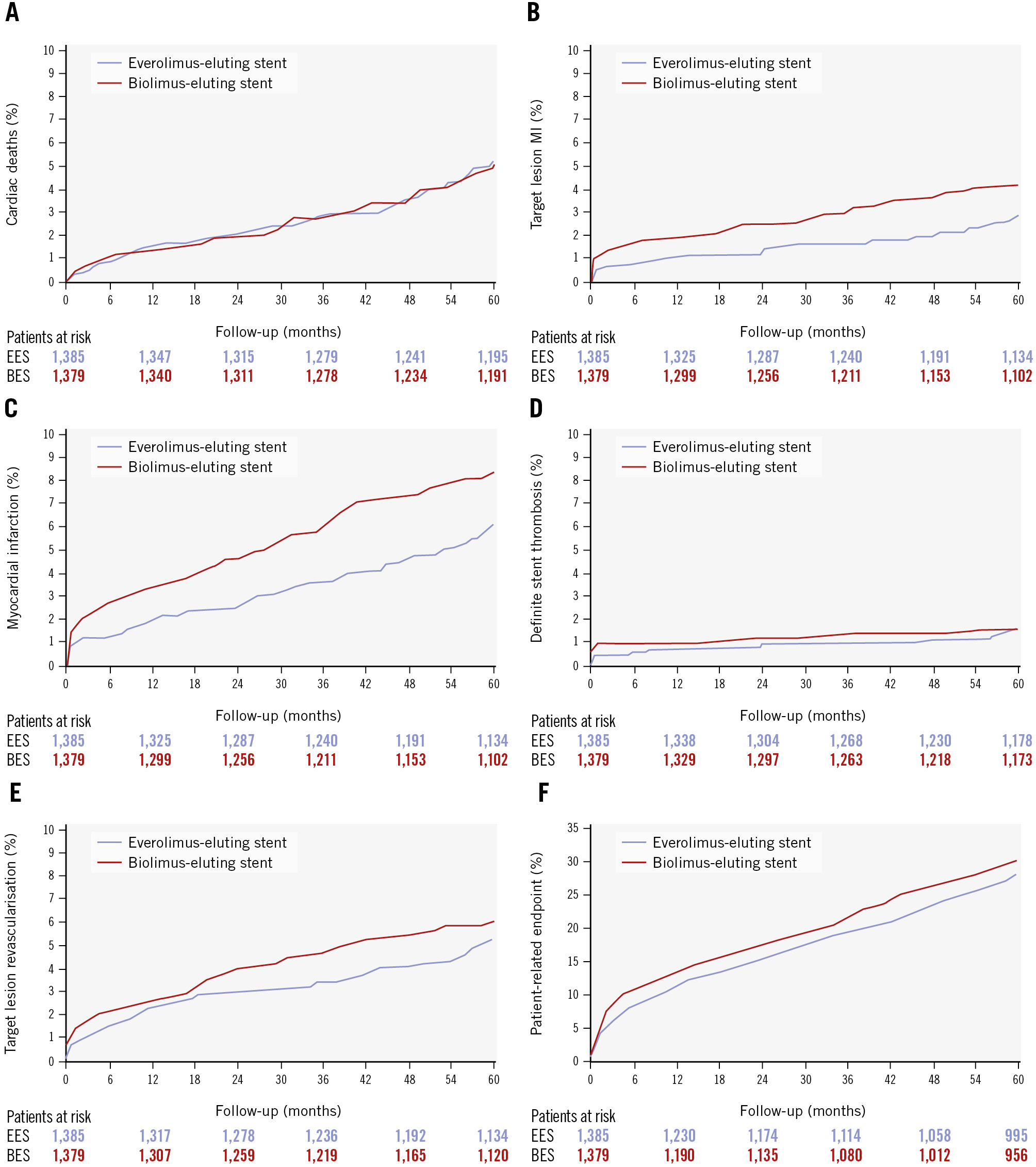

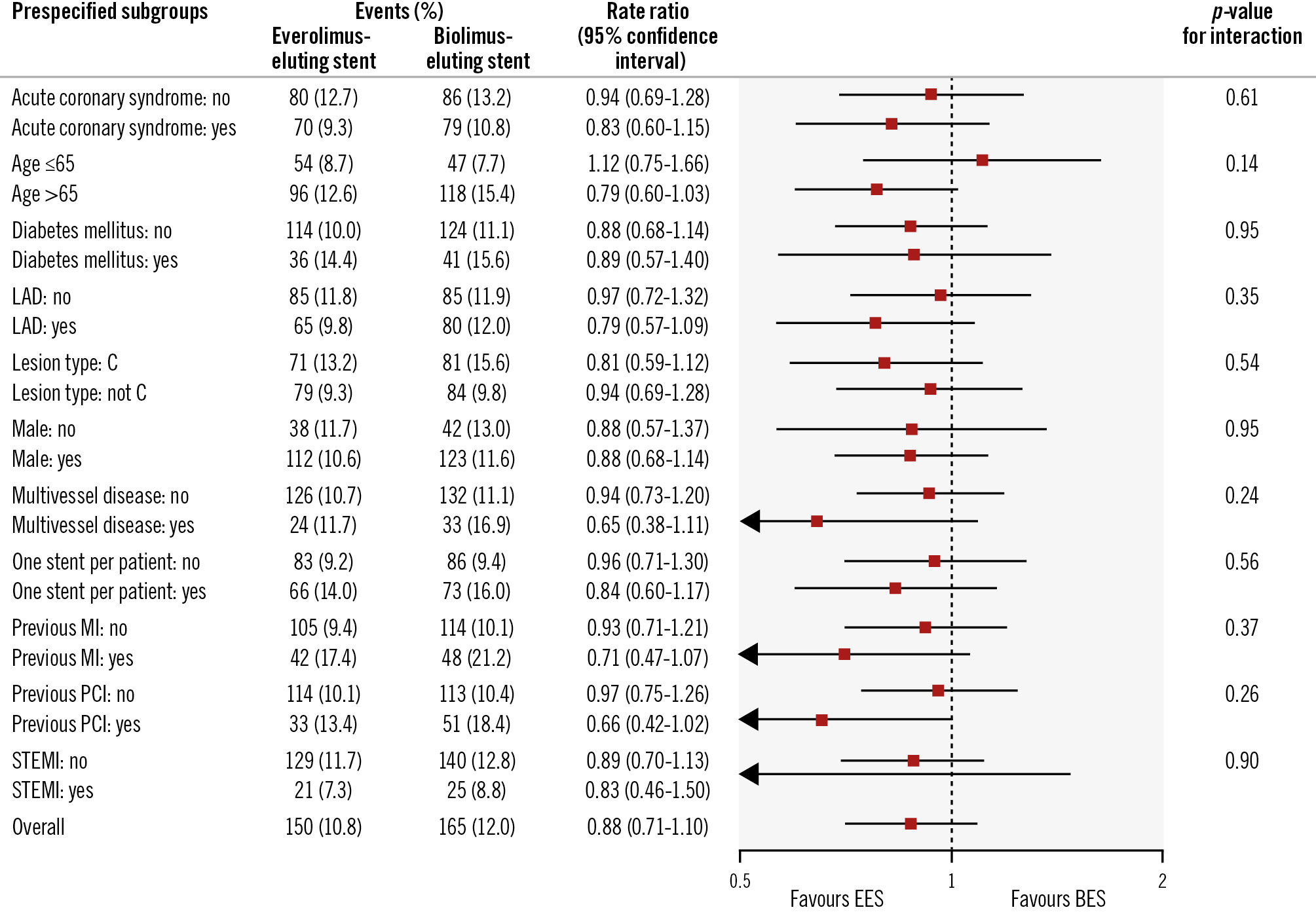

The clinical outcomes at 5 years are presented in Table 3, and the major secondary outcomes are illustrated in Figure 1. At 5-year follow-up, TLF had occurred in 150 (10.8%) patients assigned to the EES and in 165 (12.0%) patients assigned to the BES (rate ratio [RR] 0.88, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.71-1.10). The rates of all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, TVR, TLR, and the patient-related composite endpoint did not differ significantly between the two stent groups. However, the rates of all MI (EES 85 [6.1%] vs BES 116 [8.4%]; RR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.54-0.95) and MI not clearly attributable to a non-target lesion (39 [2.8%] vs 58 [4.2%]; RR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.44-0.98) were reduced by approximately one-third in the EES group. Although this difference in MI was primarily observed within the first year, numerical differences were present for both MI parameters during years 1-5, but confidence intervals were wide. Moreover, neither the occurrence of definite ST (1.6% in both groups) nor of definite or probable ST (1.9% vs 2.0%) explained the differences in MI rates. Stratified analysis by sex showed no difference in TLF rates for either female (EES 38 events [11.7%] vs BES 42 events [13%]; RR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.57-1.37) or male patients (EES 112 events [10.6%] vs BES 123 events [11.6%]; RR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.68-1.14). Similarly, no difference regarding TLF was seen for the stents when stratified for patients with (EES 36 events [14.4%] vs BES 41 events [15.6%]; RR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.57-1.40) or without diabetes (EES 114 events [10%] vs BES 124 events [11.1%]; RR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.68-1.14). Finally, very late stent thrombosis was rare for both stent types (EES: n=12 [0.9%], BES: n=9 [0.7%]; RR 1.32, 95% CI: 0.56-3.14).

Figure 2 shows the prespecified subgroup analyses. No significant interaction for any subgroup was observed.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics.

| SYNERGYEES (N=1,385) | BioMatrix NeoFlex BES (N=1,379) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66±11 | 66±11 |

| Male | 1,060 (77) | 1,056 (77) |

| Family history of coronary disease | 561 (45) | 582 (47) |

| Current smoker | 418 (32) | 385 (29) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250 (18) | 262 (19) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28±5 | 28±5 |

| Hypertension | 777 (57) | 795 (58) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 748 (55) | 724 (53) |

| History of myocardial infarction | 241 (17) | 226 (17) |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention | 246 (18) | 277 (20) |

| Previous coronary artery bypass operation | 144 (10) | 112 (8) |

| Clinical presentation | ||

| Stable angina | 578 (42) | 596 (43) |

| Non-STEMI/UAP | 466 (34) | 445 (32) |

| STEMI | 287 (21) | 284 (21) |

| Other | 54 (4) | 54 (4) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | ||

| 0 | 743 (54) | 767 (56) |

| 1-2 | 454 (33) | 435 (32) |

| 3+ | 188 (14) | 177 (13) |

| Values are n (%) or mean±standard deviation. BES: biolimus-eluting stent; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; UAP: unstable angina pectoris | ||

Table 2. Baseline lesion and procedural characteristics.

| SYNERGYEES | BioMatrix NeoFlex BES | |

|---|---|---|

| Total no. of lesions | 1,725 | 1,670 |

| Target lesions per patient | ||

| 1 | 1,076 (78) | 1,084 (79) |

| 2 | 242 (18) | 244 (18) |

| 3 | 56 (4) | 49 (4) |

| >3 | 11 (0.8) | 2 (0.1) |

| >1 lesion treated | 309 (22) | 295 (21) |

| Target lesion location | ||

| Left main artery | 43 (2.5) | 33 (2.0) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 718 (42) | 712 (43) |

| Left circumflex artery | 367 (21) | 375 (23) |

| Right artery | 561 (33) | 518 (31) |

| Saphenous vein graft | 36 (2.1) | 32 (1.9) |

| Lesion type | ||

| A | 220 (13) | 218 (13) |

| B1 | 510 (30) | 504 (30) |

| B2 | 404 (23) | 378 (23) |

| C | 591 (34) | 570 (34) |

| Chronic total occlusion | 79 (4.6) | 91 (5.5) |

| Bifurcation lesion | 291 (17) | 271 (16) |

| Lesion size | ||

| Lesion length, mm | 15 (10-20) | 15 (10-21) |

| Lesion length >18 mm | 588 (34) | 579 (35) |

| Reference diameter, mm | 3.4 (3.0-3.7) | 3.3 (3.0-3.6) |

| Small vessels <2.75 mm | 276 (16) | 259 (16) |

| Total stent length, mm | ||

| Per patient | 24 (16-35) | 24 (14-33) |

| Per lesion | 20 (16-24) | 18 (14-25) |

| >1 stent used | 473 (34) | 456 (33) |

| Maximum balloon pressure, atm | 16 (14-20) | 16 (14-20) |

| Direct stenting | 205 (12) | 212 (13) |

| Length of procedure, min | 20 (13-33) | 21 (14-34) |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 6.0 (3.4-10.5) | 6.0 (3.5-11.0) |

| Contrast, ml | 80 (50-110) | 80 (50-120) |

| Use of GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors | 37 (2.7) | 45 (3.3) |

| Use of bivalirudin | 301 (24) | 281 (22) |

| Data are n (%) or median (interquartile range). BES: biolimus-eluting stent; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; GP: glycoprotein | ||

Table 3. Five-year clinical outcomes.

| Outcome | SYNERGYEES (n=1,385) | BioMatrix NeoFlex BES (n=1,379) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target lesion failure | 150 (10.8) | 165 (12.0) | 0.88 (0.71-1.10) | 0.27 |

| 0-1 year | 55 (4.0) | 60 (4.4) | 0.90 (0.62-1.30) | 0.57 |

| 1-5 years | 95 (7.3) | 105 (8.2) | 0.88 (0.66-1.15) | 0.34 |

| Deaths | ||||

| All-cause mortality | 190 (13.7) | 184 (13.3) | 1.03 (0.84-1.26) | 0.79 |

| 0-1 year | 38 (2.7) | 37 (2.7) | 1.02 (0.65-1.61) | 0.93 |

| 1-5 years | 152 (11.3) | 147 (11.0) | 1.03 (0.75-1.29) | 0.80 |

| Cardiac deaths | 72 (5.2) | 69 (5.0) | 1.04 (0.75-1.44) | 0.82 |

| 0-1 year | 21 (1.5) | 18 (1.3) | 1.16 (0.62-2.18) | 0.65 |

| 1-5 years | 51 (3.8) | 51 (3.8) | 1.00 (0.68-1.47) | 0.98 |

| Non-cardiac deaths | 118 (8.5) | 115 (8.3) | 1.02 (0.79-1.32) | 0.87 |

| 0-1 year | 17 (1.2) | 19 (1.4) | 0.89 (0.46-1.71) | 0.73 |

| 1-5 years | 101 (7.5) | 96 (7.2) | 1.05 (0.79-1.38) | 0.74 |

| Myocardial infarction (not clearly attributable to a non-target lesion) |

39 (2.8) | 58 (4.2) | 0.66 (0.44-0.98) | 0.04 |

| 0-1 year | 15 (1.1) | 26 (1.9) | 0.57 (0.30-1.07) | 0.08 |

| 1-5 years | 24 (1.8) | 32 (2.5) | 0.73 (0.43-1.24) | 0.24 |

| Myocardial infarction (any) | 85 (6.1) | 116 (8.4) | 0.71 (0.54-0.95) | 0.02 |

| 0-1 year | 27 (1.9) | 47 (3.4) | 0.56 (0.35-0.91) | 0.02 |

| 1-5 years | 58 (4.4) | 69 (5.3) | 0.82 (0.58-1.16) | 0.26 |

| Stent thrombosis | ||||

| Definite | 22 (1.6) | 22 (1.6) | 0.99 (0.55-1.79) | 0.98 |

| 0-1 year | 10 (0.7) | 13 (0.9) | 0.76 (0.33-1.74) | 0.52 |

| 1-5 years | 12 (0.9) | 9 (0.7) | 1.32 (0.56-3.14) | 0.53 |

| Probable | 5 (0.4) | 6 (0.4) | 0.83 (0.25-2.72) | 0.75 |

| 0-1 year | 5 (0.4) | 6 (0.4) | 0.83 (0.25-2.72) | 0.76 |

| 1-5 years | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Definite or probable | 27 (1.9) | 28 (2.0) | 0.96 (0.56-1.63) | 0.87 |

| 0-1 year | 15 (1.1) | 19 (1.4) | 0.78 (0.40-1.54) | 0.48 |

| 1-5 years | 12 (0.9) | 9 (0.7) | 1.32 (0.56-3.14) | 0.52 |

| Target vessel revascularisation | 110 (7.9) | 124 (9.0) | 0.87 (0.67-1.13) | 0.29 |

| 0-1 year | 50 (3.6) | 54 (3.9) | 0.91 (0.62-1.35) | 0.64 |

| 1-5 years | 60 (4.6) | 70 (5.4) | 0.84 (0.59-1.18) | 0.31 |

| Target lesion revascularisation | 72 (5.2) | 83 (6.0) | 0.85 (0.62-1.17) | 0.33 |

| 0-1 year | 32 (2.3) | 35 (2.5) | 0.90 (0.56-1.46) | 0.68 |

| 1-5 years | 40 (3.0) | 48 (3.7) | 0.82 (0.54-1.25) | 0.35 |

| Patient-related endpoint | 390 (28.2) | 420 (30.5) | 0.90 (0.78-1.03) | 0.13 |

| 0-1 year | 155 (11.2) | 187 (13.6) | 0.80 (0.65-1.00) | 0.05 |

| 1-5 years | 235 (19.1) | 233 (19.6) | 0.97 (0.81-1.16) | 0.75 |

| Values are n (%), unless otherwise indicated. The cumulative incidence of any particular event in the given period was calculated with death as the competing risk. The patient-related composite outcome included all deaths, all myocardial infarctions, or any revascularisations. The stent-related composite outcome included cardiac deaths, target vessel myocardial infarctions, or ischaemia-driven target lesion revascularisations. BES: biolimus-eluting stent; CI: confidence interval; EES: everolimus-eluting stent | ||||

Figure 1. Time-to-event curves for major secondary endpoints at 5-year follow-up. A) Cardiac death. B) Target lesion-related myocardial infarction. C) Myocardial infarction (any). D) Definite stent thrombosis. E) Target lesion revascularisation. F) Patient-related composite endpoint, defined as a composite of death, any myocardial infarction, and any revascularisation. BES: biolimus-eluting stent; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; MI: myocardial infarction

Figure 2. Prespecified subgroup analyses for the primary endpoint at 5-year follow-up. The p-values in the forest plot are all 2-sided for interaction. BES: biolimus-eluting stent; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; LAD: left anterior descending artery; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Discussion

This 5-year follow-up in a randomised, multicentre, all-comer, non-inferiority trial confirms previous 1-year results12 of similar rates of TLF in a head-to-head comparison of the thin-strut platinum-chromium absorbable-polymer SYNERGY EES versus the relatively thick-strut stainless-steel absorbable-polymer BioMatrix NeoFlex BES12. Our main finding is that TLF rates were comparable for the EES and BES groups. Moreover, two of the individual components of the primary endpoint as well as TVR and all-cause mortality were comparable in the two groups at 5-year follow-up. However, the rate of myocardial infarctions that were not clearly attributable to a non-target lesion and the rate of all myocardial infarctions were both significantly lower for the thin-strut EES-treated group. Very late stent thrombosis, an important secondary endpoint in this 5-year follow-up analysis, did not differ between the groups and was less than 1% for both stent types during the 1- to 5-year follow-up period. These must be regarded as excellent results considering that the complexity of the patient population represents daily clinical practice and given the high rate of patients with acute coronary syndromes.

Comparison to other stent trials

The SYNERGY EES is a modification of the first everolimus-eluting stent, which was based on a cobalt-chromium alloy and utilised a permanent fluoropolymer. Changes included a platinum-chromium alloy, to increase radial strength and radiopacity13, and a fast-absorbable polymer14. While long-term outcome data are available for several commercially available DES, including the BES, there are currently limited long-term follow-up data for the SYNERGY EES. The current study is the first to provide 5-year follow-up data for the comparison of the SYNERGY EES versus a BES. Two randomised trials have provided 5-year TLF data for the SYNERGY EES versus the PROMUS Element Plus BTK EES (Boston Scientific), the latter using a cobalt-chromium alloy and a permanent fluoropolymer. In the EVOLVE II randomised trial (N=1,684 patients), SYNERGY EES and PROMUS Element Plus BTK EES demonstrated similar 5-year TLF rates (14.3% and 14.2%)14. Likewise, there was no difference between SYNERGY EES and PROMUS Element Plus BTK EES at 5-year follow-up in the smaller EVOLVE China trial (N=412)15. In the randomised BIO-RESORT trial (N=3,514), 5-year TVF rates for the Orsiro sirolimus-eluting stent (Biotronik) were compared 1:1:1 with the SYNERGY EES and Resolute Integrity zotarolimus-eluting stents (Medtronic)16. TVF rates were numerically lowest in the SYNERGY EES arm (11.6%), followed by the Orsiro stent (12.7%), and highest for the Resolute Integrity stent (14.1%), although the study did not show significant differences. Our series of SORT OUT trials, with the BES as the test stent (SORT OUT V) or the comparator stent (SORT OUT VI, VII, VIII), have all shown non-inferiority regarding the primary 1-year endpoint and the final 3-year (SORT OUT VI)17 or 5-year follow-up (SORT OUT VII)6811171819 when compared to the Cypher sirolimus-eluting stent (Cordis)18, the Resolute Integrity zotarolimus-eluting stent1117, the Orsiro sirolimus-eluting stent78, and the SYNERGY EES (present study).

Does strut thickness matter?

It has been hypothesised that further improvement may be possible with the use of very thin-strut stents. The current study, despite a considerable difference in strut thickness between the thin-strut platinum-chromium SYNERGY stent and the stainless-steel BES, did not indicate that strut thickness has a major impact. However, in the bare metal stent era, two (elegant) studies showed that stents with thin 50 μm struts reduced angiographic and clinical restenosis by approximately 40% as compared to either similar or dissimilar stent designs with 140 μm struts2021. In the BIOFLOW-V study (n=1,334 patients; 2:1 randomisation), the 60 μm absorbable-polymer Orsiro stent was compared with the 81 μm durable-polymer XIENCE EES stent (Abbott)4. At 5-year follow-up, TLF was the same for these stents22. Likewise, BIO-RESORT16 and SORT OUT VII7 compared the ultrathin-strut Orsiro stent with thicker-strut stents, up to 120 μm, without establishing superiority. Thus, these results do not suggest that strut thickness in the range of 60-120 μm is a major independent risk factor of 5-year TLF when comparing contemporary DES. Furthermore, a stratified analysis by sex and diabetes failed to show differences between the two study stents regarding the 5-year TLF endpoint. Still, the difference in strut thickness may explain the lower incidence of myocardial infarction observed in the EES group.

Very late stent thrombosis

As previously reported, the rates of definite ST were low in this all-comer cohort, although more than half of the patients had acute coronary syndromes and one-third of patients had complex type C lesions12. An important finding in the current study is the very low incidence of very late stent thrombosis, which was <1% for both DES between 1- and 5-year follow-up. This result shows that the currently available DES are safe to use despite the continued presence of metal struts in the coronary arteries. Major efforts have been made to develop absorbable devices, but such devices have so far failed to show equivalent or superior results23. Further, there is currently a focus on the use of drug-coated balloons (DCBs) as an alternative to stent implantation, at least in specific lesion subgroups. With the current rates of very late stent thrombosis, it may be difficult to show superiority when comparing DCBs versus DES.

Combined with data from other 5-year outcome trials, this provides solid evidence for the long-term safety of the SYNERGY EES, which utilises a polymer that is absorbed faster than other DES with absorbable polymers151624.

Limitations

The SORT OUT trials use registry-based event detection. The advantages of registry-based event detection include the possibility of large-scale, low-cost, investigator-driven studies and high rates of consent from routine clinical care patients due to the absence of study-related follow-up. The endpoints are adjudicated by an endpoint committee like the outcome assessment in conventional randomised clinical trials.

Conclusions

At the final 5-year follow-up, TLF was comparable for EES and BES. The incidence of myocardial infarction, however, was lower in patients randomised to EES versus BES implantation.

Impact on daily practice

Percutaneous coronary intervention with implantation of drug-eluting stents is the preferred method of revascularisation for the majority of patients with obstructive coronary artery disease. In the large, randomised SORT OUT VIII trial with 5-year follow-up, we showed that the thin-strut everolimus-eluting SYNERGY stent and the biolimus-eluting BioMatrix NeoFlex stent had comparable rates of target lesion failure after 5 years when used to treat obstructive coronary artery disease. However, the rates of myocardial infarction were lower in patients treated with the thin-strut SYNERGY stent. The excellent safety results with newer-generation drug-eluting stents may stimulate attempts to reduce the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy, particularly in patients at high risk of bleeding events.

Contributors

M. Maeng drafted the study protocol. J. Kahlert and M. Maeng were responsible for data management and for the design and implementation of the statistical analysis. All the other authors either enrolled patients and/or contributed to data collection. N. Støttrup and M. Maeng drafted the manuscript and revised it with contributions by E.H. Christiansen, B. Raungaard, J. Kahlert, C.J. Terkelsen, S.D. Kristensen, T. Thim, L. Jakobsen, R.V. Jensen, S.E. Jensen, K.T. Veien, and L.O. Jensen. M. Maeng was responsible for the final submission. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed with its contents.

Coordinating centre: Scandinavian Organization for Randomized Trials with Clinical Outcome (SORT OUT), Aarhus University Hospital, Skejby, Aarhus, Denmark.

Clinical events committee

Professor Kristian Thygesen, Dr. Jan Ravkilde and Professor Henning Rud Andersen (Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark).

Data and monitoring centre

Department of Epidemiology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark (Johnny Kahlert).

Conflict of interest statement

E.H. Christiansen has received grants from OrbusNeich and Biotronik to his institution. S.D. Kristensen has received lecture fees from Aspen and AstraZeneca; and research grants from Dorsia. L.O. Jensen has received research grants from Biotronik, OrbusNeich, Biosensors, and Terumo to her institution; and honoraria from Biotronik. M. Maeng reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boston Scientific, and Novo Nordisk, outside the submitted work; is supported by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant number NNF22OC0074083); has received lecture and/or advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novo Nordisk; has received research grants from Philips, Bayer, and Novo Nordisk; has received a travel grant from Novo Nordisk; has ongoing institutional research contracts with Janssen, Novo Nordisk, and Philips; and has equity interests in Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly & Company, and Verve Therapeutics. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.