Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Bioresorbable scaffolds (BRS) were designed to “leave nothing behind” by providing temporary scaffolding, thereby overcoming the limitations of permanent metallic stents in the treatment of coronary artery disease at long-term follow-up. These limitations include ongoing triggers for neoatherosclerosis, resulting in in-stent restenosis rates of 2-3% per year and in-stent thrombosis rates of 0.1-0.2% per year at long-term follow-up. Furthermore, permanent caging with metallic stents hampers vasomotion and vessel pulsatility, and can also make future coronary bypass grafting difficult123.

The Absorb bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS; Abbott) was the first BRS to obtain the European Conformity (CE) mark and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval. In September 2017, as a result of disappointing outcomes, especially increased risk of scaffold thrombosis, the device was withdrawn from the market.

However, long-term follow-up, (i.e., when the scaffold is fully resorbed after approximately 3-4 years) of these ABSORB trials could provide us with insights as to whether the "leave nothing behind" is the 4th rosy prophecy or a utopian idea4.

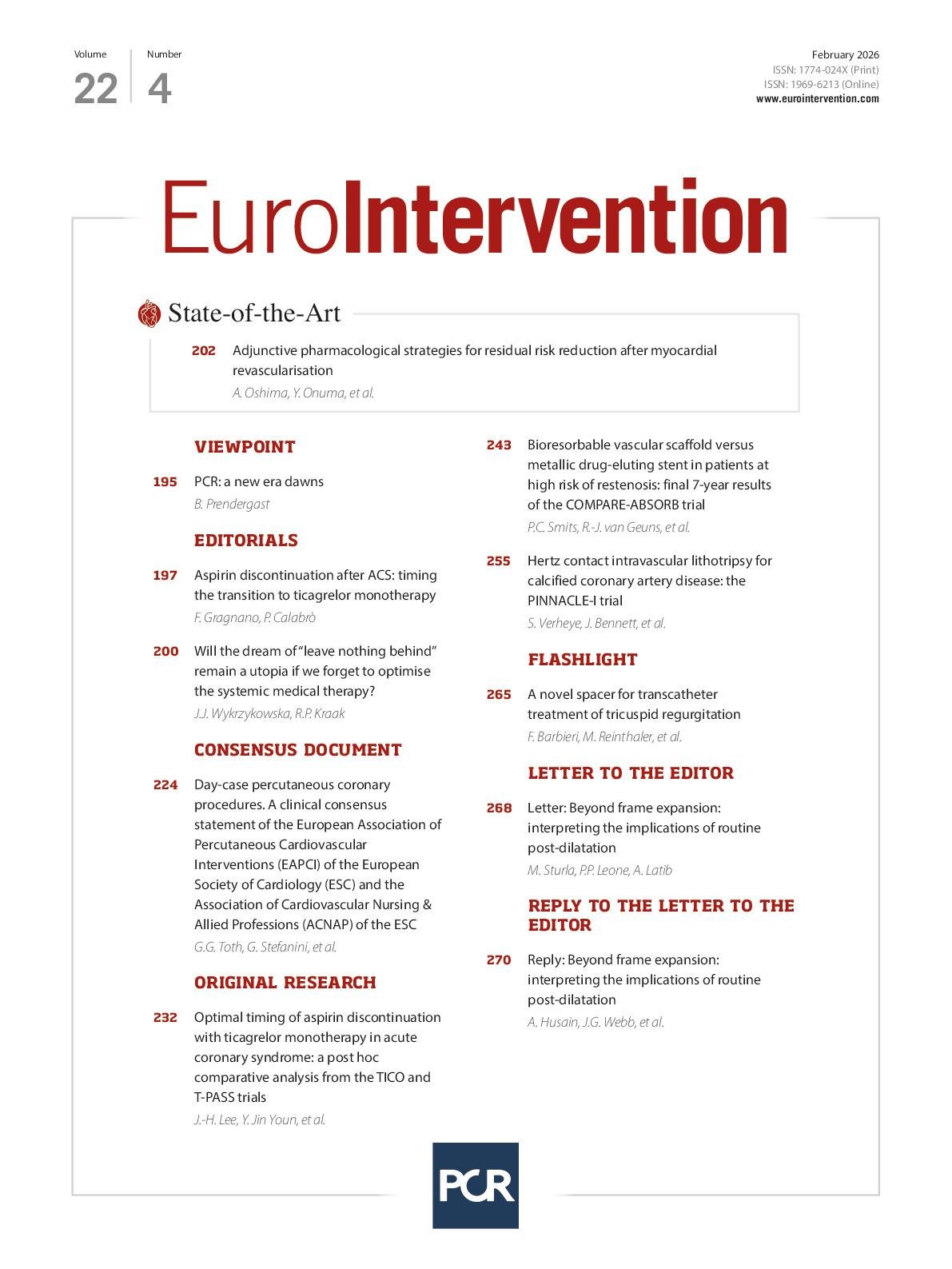

In this issue of EuroIntervention, Smits and his colleagues report on the results of the 7-year follow-up of the COMPARE-ABSORB trial in order to provide us with answers on the long-term outcomes of the “leave nothing behind” strategy5.

In short, the COMPARE-ABSORB trial was a prospective, randomised, controlled, multicentre trial comparing the Absorb BVS and the XIENCE everolimus-eluting stent (EES; Abbott) for the treatment of coronary artery disease in a high-risk patient population. The trial enrolled 1,670 of the intended 2,100 patients between 2015 and 2017 and was prematurely stopped on recommendation from the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, based on safety concerns seen in the interim analysis: namely, increased risk of scaffold thrombosis at 1-year follow-up (1.9% vs 0.6% for BVS and EES, respectively)6. These results were in line with other randomised controlled trials comparing BVS and EES, such as ABSORB III and AIDA78. The trial, however, met its co-primary endpoint of non-inferiority for target lesion failure (TLF), a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction related to the target vessel, and clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation (TLR) of the BVS compared to the EES. This current analysis reports on the second co-primary endpoint of superiority of the BVS compared to the EES in a landmark analysis between the 3- and 7-year follow-up.

First, the authors should be complimented on the current analysis, especially for collecting the complete follow-up of 95% of the enrolled patients, with vital status known for 96% of the patients. Furthermore, an independent clinical event committee evaluated all events during this 7-year period, making this report scientifically robust.

However, the result of the current landmark analysis is, for believers in the benefit of the “leave nothing behind” strategy, rather disappointing. Despite a mandatory dedicated implantation protocol in the trial for the BVS, the Kaplan-Meier event rates for TLR of BVS and EES run parallel between 3 and 7 years, with a yearly event rate for both BVS and EES of 1-2.2%. There are no signs of the event curves crossing over in favour of the BVS. Even more striking is the increased incidence of clinically indicated TLR in the landmark analysis for BVS as compared with EES (4.4% vs 2.2% respectively, hazard ratio 1.97, 95% confidence interval: 1.08-3.60; p=0.024). Luckily, the earlier safety issue of scaffold thrombosis seems to have abated in the long term.

The unsatisfying results of COMPARE-ABSORB are in line with the results of the 5-year analysis of the AIDA Trial, in which an annual TLF rate of 1.4-2.5% was seen after 3-year follow-up for both the BVS arm and the EES arm9. Is there no silver lining in the “leave nothing behind” story when bioresorbable polylactic acid scaffolds are used? In the Absorb programme that included all Abbott Vascular sponsored trials, ABSORB II, III, and IV did show a trend in their 3- to 5-year landmark analysis, as the Kaplan-Meier curves for TLF were converged around 5 years10. Perhaps it would be of interest to collect combined long-term (7- to 10-year) follow-up data from the Absorb programme, AIDA, and COMPARE-ABSORB trials.

How do we explain these higher TLR rates in the BVS arm in the long term, years after complete resorption of the device? More importantly, are the continued revascularisation events after uncaging the vessel also applicable to other approaches, such as drug-eluting balloon (DEB)-treated lesions or other BRS, such as magnesium-based scaffolds? Our answers here can be only speculative, but one potential cause of the late events in the Absorb BVS-treated patients is the altered blood flow and endothelial shear stress patterns due to the 160 μm thick struts, which could be a nidus for neointimal proliferation distal to the scaffold11. Another aspect could be the resorption process of the polylactic acid-based scaffold, which degrades and resorbs in an acidic and inflammatory intramural milieu, creating a potential trigger for late neoatherosclerosis. If these two hypotheses are true then there may be an easy fix to the late TLR problem: decreasing the strut thickness, using a magnesium alloy or implanting no device at all, and using a DEB. The reality is perhaps not that simple. In addition to developing new devices, we must not forget the importance of optimal medical therapy (OMT), especially lowering lipid levels with statins, ezetimibe, or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors. At 7-year follow-up, only 88% of the high-risk patients enrolled in the COMPARE-ABSORB trial were treated with statins. This is despite the fact that we all know that strict adherence to lipid-lowering medication decreases the number of lipid-rich plaques and the risk of (neo)atherosclerosis, leading to improved clinical outcomes12.

Only future trials of DEBs versus metallic DES and thin-strut BRS on the background of OMT and their long-term follow-up will provide us with the answers as to whether the dream of “leave nothing behind” will come true or remain a utopia. In the meantime, after achieving an optimal PCI result, we must ensure that our patients remain on the best and optimal medical treatment to prevent coronary atherosclerosis and future events.

Conflict of interest statement

J.J. Wykrzykowska declares institutional research grants from Medtronic, and US2.ai; and institutional honoraria from Medtronic, Abbott, BSC, Meril Life Sciences, Medis Medical Imaging, Sinomed, SMT, and Cordis. R.P. Kraak has no conflicts of interest to declare.