Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

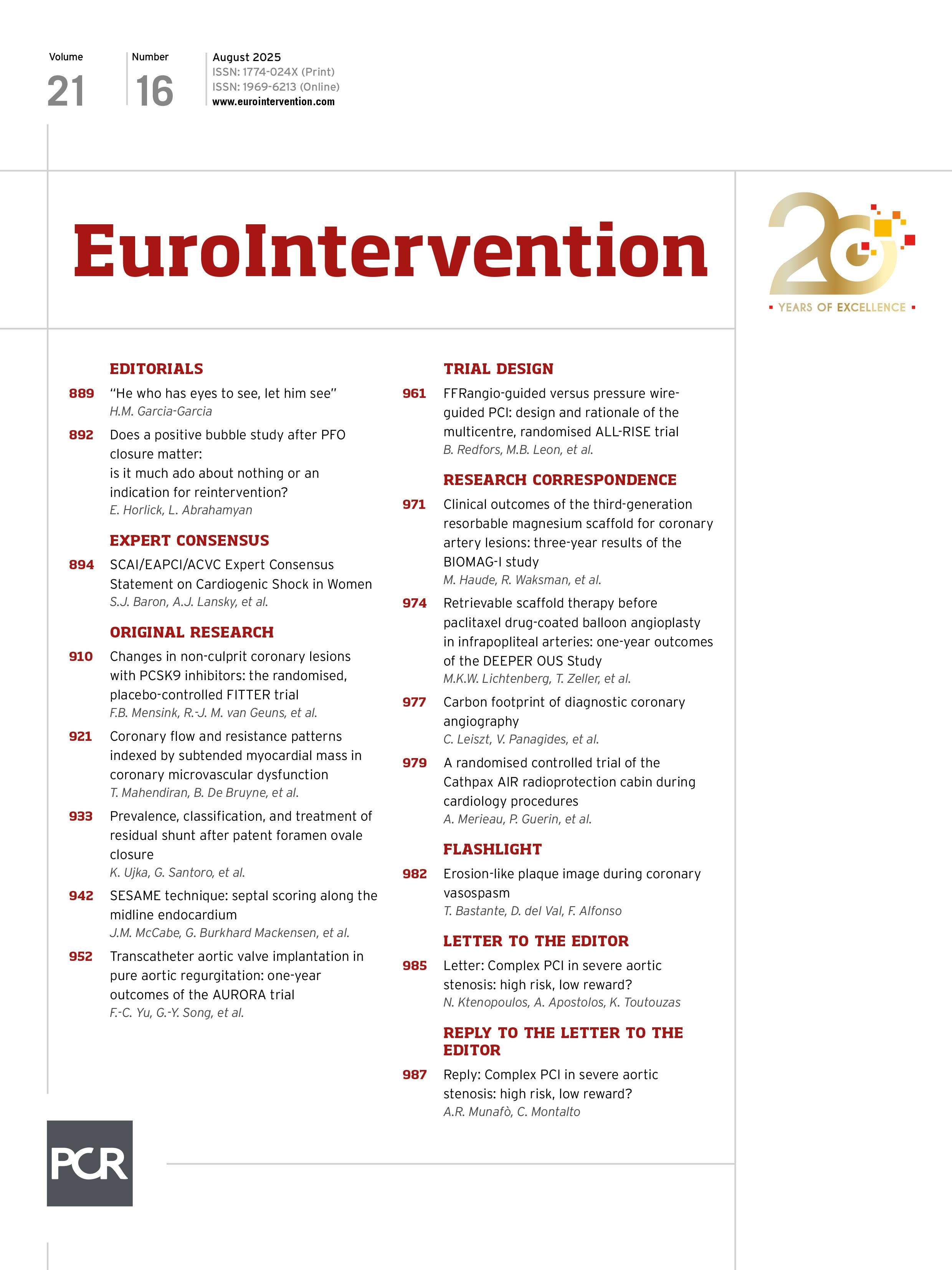

We read with great interest the recent publication by Montalto et al, “Outcomes of complex, high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the ASCoP registry”1. The authors are to be congratulated for addressing such a critical and emerging clinical challenge, complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS). However, certain aspects of the study findings warrant further discussion.

Firstly, the study highlights substantial adverse event rates associated with complex/high-risk PCI in patients with severe AS, irrespective of whether PCI was performed concomitantly or staged with transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Notably, early safety occurred in 55.9% of cases overall, device success in 74.8% of cases overall, and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) remained considerable with a percentage of 19.8%. These outcomes stand in contrast to both data from randomised trials and real-world studies, which reported device success rates of about 90% and 87% and early safety rates of about 75% and 76%, respectively, with fewer MACCE23.

These findings raise fundamental questions regarding the overall benefit-risk ratio of performing complex PCI in this fragile population. The procedural risks appear disproportionately high when weighed against the uncertain incremental clinical benefits, particularly in a cohort marked by severe baseline frailty and often limited life expectancy. Notably, a large majority of patients in this study (N=440/519, 84.8%) underwent PCI for chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) – a subgroup in which contemporary evidence increasingly supports conservative management4. Thus, while revascularisation prior to TAVI may be justified in the presence of critical coronary anatomy (e.g., unprotected left main or severe proximal lesions), the threshold for intervention – particularly for non-left main, non-culprit lesions – should be reconsidered, favouring a more conservative, physiology-guided approach.

Secondly, an interesting finding was the relatively low usage of radial artery access for both staged and concomitant PCI in the registry (N=293/519, 56.6% overall). This contrasts with current evidence supporting radial access as the first-line approach in PCI, even in patients undergoing high-risk or complex PCI, or with acute coronary syndrome as the indication in high-risk and complex cases. For instance, the MATRIX trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01433627) demonstrated that radial access significantly reduces major bleeding and mortality, without increasing ischaemic complications or compromising procedural success, and the Color trial confirmed that even large-bore complex PCI can be performed safely and effectively via transradial access, with a dramatic reduction in access site complications compared to via femoral access5.

Considering that vascular complications and major bleeding were among the leading adverse events observed in the ASCoP registry, it could be considered that a wider adoption of radial access as the first-line vascular access could have improved the safety and the outcomes.

In conclusion, Montalto et al have provided real-world data that should encourage reconsideration of both the value of complex PCI in patients with CCS and severe AS and the preferable vascular access in such patients.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this letter to declare.