Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: The role of non-culprit plaque rupture (a sign of pancoronary vulnerability) on long-term clinical outcomes remains unclear.

Aims: We aimed to investigate the association between non-culprit plaque rupture and long-term clinical outcomes.

Methods: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients who had undergone 3-vessel optical coherence tomography before interventional therapy were studied. Patients and lesions were categorised into groups with and without non-culprit plaque rupture. Furthermore, non-ruptured thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) was defined as a lesion with TCFA but not plaque rupture. All enrolled patients were followed for up to 5 years. The study endpoint was major adverse cardiac events (MACE), including cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and unplanned ischaemia-driven revascularisation.

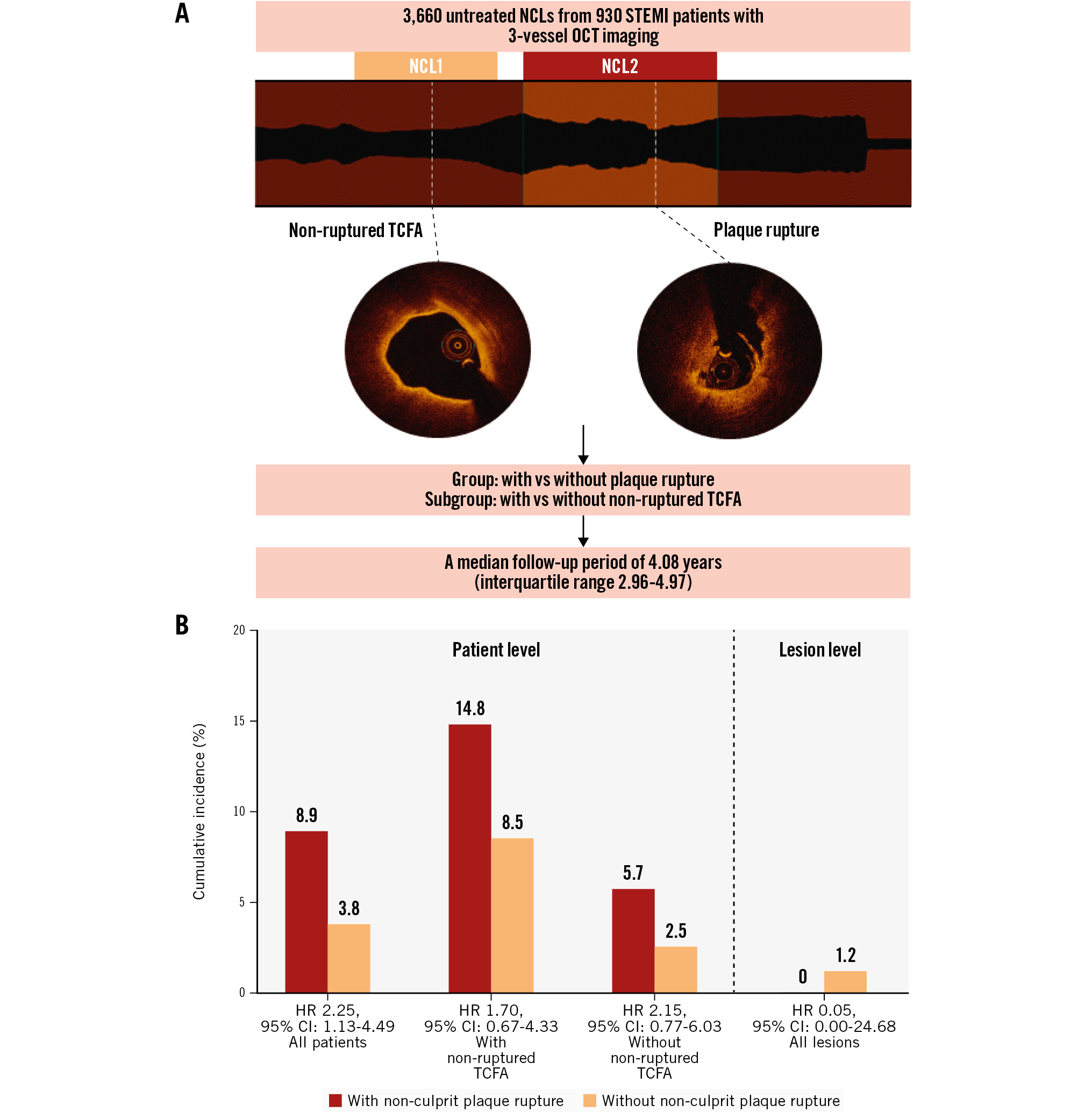

Results: A total of 930 STEMI patients with 3,660 non-culprit lesions were included. Non-culprit plaque rupture was detected in 165 patients and 209 lesions. During a median 4.1-year follow-up, non-culprit lesion-related MACE occurred more frequently in patients with versus without plaque rupture (hazard ratio [HR] 2.25, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.13-4.49; p=0.021). However, non-culprit lesion-related MACE were similar for lesions with versus without plaque rupture (HR 0.05, 95% CI: 0.00-24.68; p=0.336). Furthermore, non-ruptured TCFA was identified in 214 patients and 281 lesions. Multivariable analysis demonstrated that non-ruptured TCFA was significantly associated with non-culprit lesion-related MACE, whereas plaque rupture was not, at both the patient and lesion levels.

Conclusions: Patients with non-culprit plaque rupture had a poor long-term prognosis, which is predominantly due to the effect of non-ruptured TCFA. Non-ruptured TCFA, not plaque rupture, can identify lesions at increased risk of subsequent events.

Non-culprit lesions are frequently detected by optical coherence tomography (OCT) in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and play a non-negligible role in recurrent cardiac ischaemic events12. Histopathological analyses have elucidated the critical morphological features (a large lipid-rich necrotic core overlying a thin [<65 μm] fibrous cap) of lesions predisposed to rupture and subsequent myocardial infarction (MI)3. Plaque rupture can also happen without initially becoming clinically overt. Data from OCT studies demonstrated that non-culprit plaque rupture was not unusual (occurring in about 20% of cases) and was associated with increased short-term recurrent event risk45. However, studies on the long-term prognostic value of non-culprit plaque rupture are lacking. In addition, during coronary atherosclerosis, thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) is considered a precursor lesion of plaque rupture, and both are considered in vivo equivalents of high-risk plaque67. The only difference between TCFA and plaque rupture is that the fibrous cap is intact in a TCFA, whereas in plaque rupture, it is disrupted. Of note, OCT-identified TCFA at the non-culprit lesion has proved to be strongly predictive of long-term adverse events8. Nevertheless, the kind of high-risk plaque phenotype (plaque rupture or non-ruptured TCFA or both) that contributes more to long-term adverse events remains undefined. To this end, we performed a 3-vessel OCT study to investigate the role of a high-risk plaque phenotype within non-culprit segments in predicting long-term recurrent adverse cardiac events in the STEMI population.

Methods

Study population

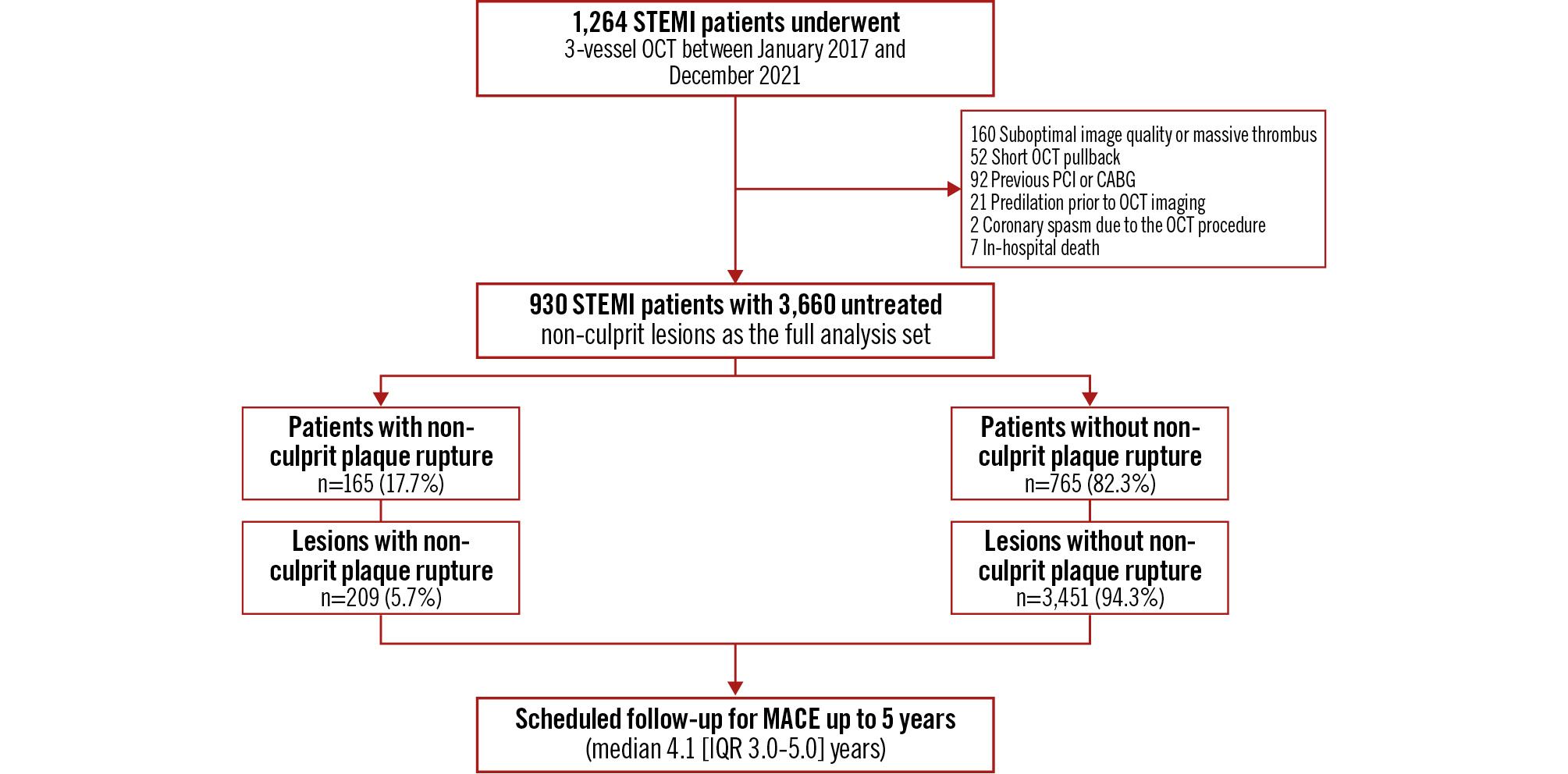

From January 2017 to December 2021, 1,264 STEMI patients (≥18 years old) who underwent OCT imaging of all three major epicardial coronary arteries were selected at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Harbin, China). Patients with suboptimal OCT imaging quality (n=160), short OCT pullback (n=52), previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (n=92), predilation before OCT imaging (n=21), coronary spasm due to the OCT procedure (n=2), or in-hospital death (n=7) were excluded from this study. Finally, 930 STEMI patients with 3,660 non-culprit lesions were included (Figure 1). Patients and lesions were classified according to the OCT-identified plaque rupture at the non-culprit site. The diagnosis criteria of STEMI and conventional risk factors, as well as quantitative coronary angiographic analysis, are provided in Supplementary Appendix 1-Supplementary Appendix 2-Supplementary Appendix 3. The Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University approved the current study, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Study flowchart. From January 2017 to December 2021, a cohort of 1,264 STEMI patients underwent 3-vessel OCT imaging following successful culprit lesion(s) revascularisation. After screening, 930 STEMI patients (165 with non-culprit plaque rupture and 765 without non-culprit plaque rupture) were enrolled in the final cohort. Clinical follow-up was conducted for a median duration of 4.1 years (IQR 3.0-5.0), with longitudinal monitoring extending up to 5 years. MACE were defined as a composite endpoint including cardiac death, non-fatal MI, and unplanned coronary revascularisation. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; IQR: interquartile range; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MI: myocardial infarction; OCT: optical coherence tomography; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

OCT image acquisition and analysis

A commercially available C7-XR/ILUMIEN OCT system (Abbott) was used to perform OCT imaging. The decision to image three vessels on OCT was at the operator’s discretion, with no prespecified angiographic criteria. OCT imaging of non-culprit lesions was performed immediately after treating the infarct-related lesion.

The culprit lesion was identified based on abnormal findings detected by coronary angiography, electrocardiography, echocardiography, or, when available, left ventricular angiography. In cases where conventional diagnostic modalities yielded inconclusive results, OCT was utilised to further identify the culprit lesion, provided it was deemed clinically appropriate. In cases where uncertainty remained, the interventional cardiologist had the discretion to perform PCI on ambiguous culprit lesions. In all, 55 patients underwent PCI for multiple vessels and were not inherently excluded from the study. Nevertheless, non-culprit lesions that underwent PCI either during the index or in planned staged procedures were excluded from the current analysis, and all remaining untreated non-culprit lesions were included.

A non-culprit lesion, as identified by OCT, was an untreated coronary segment (longitudinal extension ≥1.2 mm) with luminal narrowing (minimal lumen area less than the mean reference area) and a loss of the normal architecture of the vessel wall. An intervening reference segment of at least 5 mm on the longitudinal view was necessary to separate two lesions in the same vessel. A detailed description of quantitative and qualitative OCT analyses is presented in Supplementary Appendix 4. Of note is that the definition of plaque rupture was the presence of fibrous cap discontinuity with a cavity formed inside the plaque. TCFA was defined as a plaque with a maximum lipid arc >180° and the thinnest fibrous cap thickness (FCT) <65 μm. Non-ruptured TCFA was defined as a lesion with TCFA but without plaque rupture.

Clinical outcomes

All patients were followed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, and annually thereafter by hospital visit or phone call after discharge. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) included cardiac death, non-fatal MI, and unplanned ischaemia-driven revascularisation. Detailed definitions of the individual components of MACE are presented in Supplementary Appendix 5. The first adverse event was recorded during the follow-up period (defined by the hierarchical evaluation: cardiac death >non-fatal MI >unplanned revascularisation). Event origins were determined through baseline/event angiogram comparison, adjudicated by three experienced cardiologists who reviewed the original source documents and were unaware of the results of the imaging analyses. Using follow-up angiography, events were classified as either culprit lesion-related MACE (initially treated sites) or non-culprit lesion-related MACE (untreated segments). If the event origin location (i.e., cardiac death) was uncertain, it was classified as indeterminate. Events were included in lesion-level endpoint analysis only if the location was angiographically identifiable and had undergone baseline OCT imaging. At the lesion level, non-fatal MI/unplanned revascularisation attributed to baseline OCT-identified non-culprit lesions was also considered target vessel MI/target lesion revascularisation.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess continuous data distribution. Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation and were compared using the Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed variables are described as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are expressed as counts (proportions) and were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, depending on category cell size. Generalised estimating equations were used to compare plaque-based analysis among groups, accounting for the potential cluster effects of multiple non-culprit lesions in a single patient. Time-to-first event data are presented as Kaplan-Meier estimates and were compared by the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to evaluate the associations between plaque phenotype (plaque rupture and non-ruptured TCFA) and the study endpoints at the patient level. Mixed-effects Cox models were used to evaluate the associations between plaque phenotype (plaque rupture and non-ruptured TCFA) and the study endpoints at the lesion level. The proportional hazards assumption was satisfied for all outcomes evaluated by examining log-log survival curves or Schoenfeld’s residuals. Results were presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For patient-based analysis, the covariates were age, sex, body mass index (BMI), current smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, chronic kidney disease, and medication use (aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitor, or statin) before admission and after discharge. For lesion-based analysis, the covariates were vessel territory (right coronary artery as reference), distance to the coronary ostium, minimal lumen area, and other qualitative OCT characteristics (calcification, macrophage, microchannels, cholesterol crystals, and layered tissue) identified within the same non-culprit lesion. Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.0.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Patient-level analysis

Between January 2017 and December 2021, a total of 930 patients diagnosed with STEMI were enrolled, of whom 165 (17.7%) had non-culprit plaque rupture. Across the overall cohort, the mean age was 56.8 years, and 75.9% were male. The rate of use of antiplatelet and lipid-lowering medicine was high at baseline discharge time. Patients with non-culprit plaque rupture had higher BMI, were less frequently current smokers, and had more hypertension than patients without non-culprit plaque rupture. The blood lipid content in patients with non-culprit plaque rupture was also higher. For example, the prevalence of dyslipidaemia and the levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol were all higher among those with non-culprit plaque rupture (Table 1).

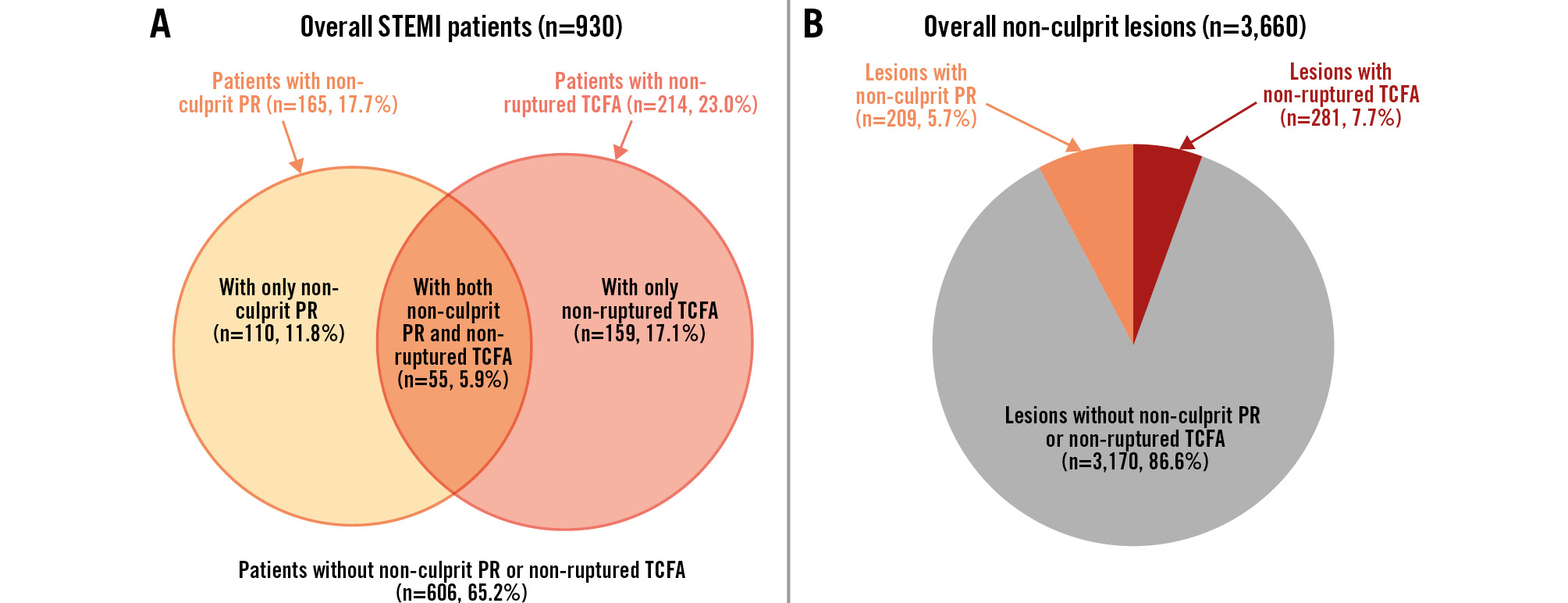

OCT characteristics at the patient level are presented in Table 2. As analysed by OCT pullback length, the non-culprit segments (174.0±34.5 mm vs 168.9±34.5 mm; p=0.083) showed no significant difference between the two groups with and without plaque rupture. The number of OCT-identified non-culprit lesions in patients with plaque rupture (5.0 [IQR 4.0-6.0] plaques per patient vs 4.0 [IQR 2.0-5.0] plaques per patient) was higher than their counterparts without plaque rupture. The proportion of vulnerable plaque characteristics was higher in patients with versus without plaque rupture (all p<0.001). As shown in Figure 2, non-ruptured TCFA was detected in 55 of 165 patients with non-culprit plaque rupture versus 159 of 765 patients without non-culprit plaque rupture (33.3% vs 20.8%; p=0.001).

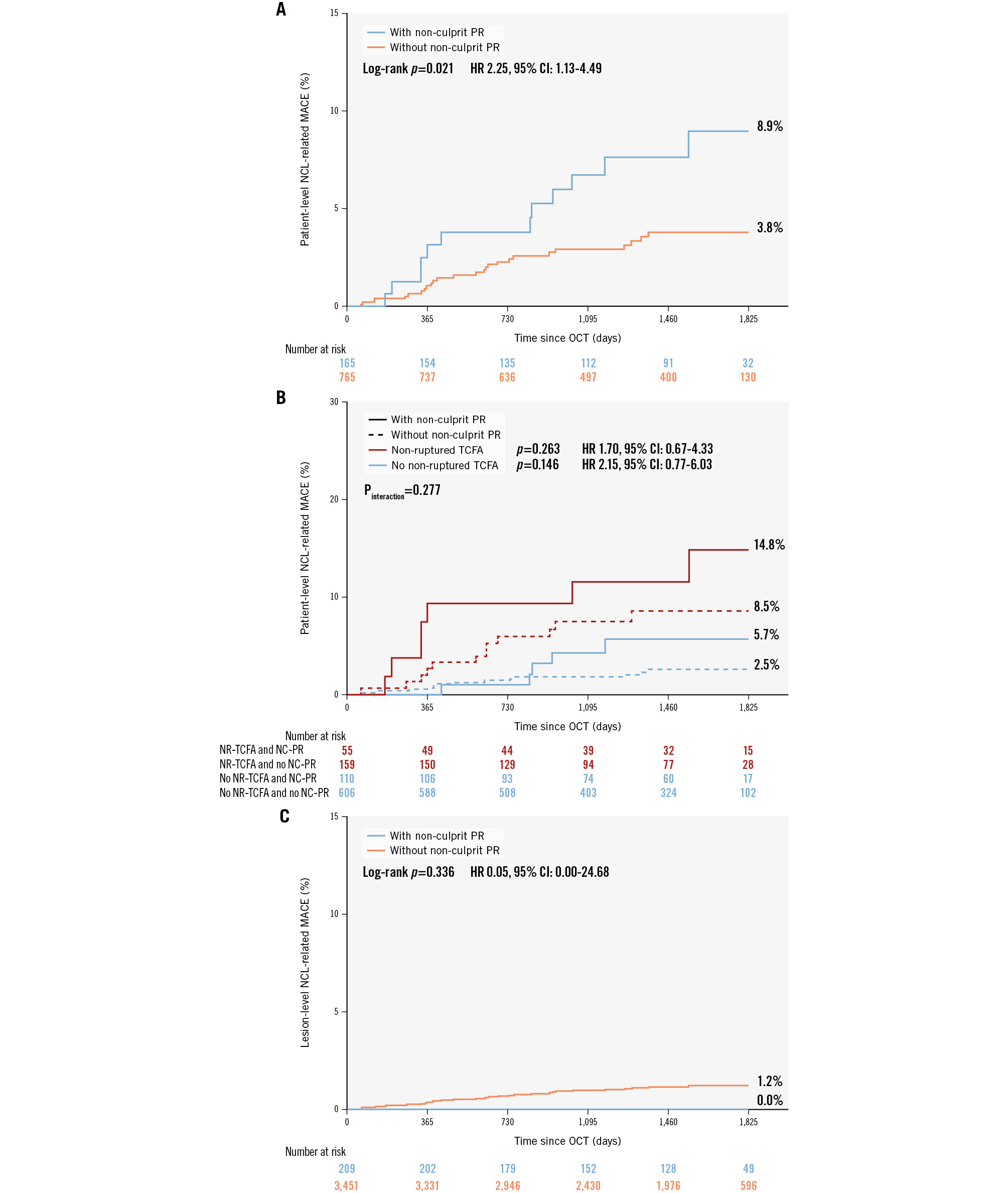

The overall median duration of follow-up was 4.08 years (IQR 2.96-4.97): 4.12 years (IQR 2.98-4.98) in patients with plaque rupture and 4.07 years (IQR 2.95-4.97) in patients without plaque rupture (p=0.181). As presented in Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 3, MACE during follow-up occurred more frequently in patients with plaque rupture than in those without, regardless of the origin of events. Specifically, the increased risk of culprit lesion-related MACE was attributable to a greater rate of non-fatal MI (5.7% vs 0.6%; HR 6.88, 95% CI: 1.94-24.39; p=0.003), and the increased risk of non-culprit lesion-related MACE was attributable to a greater rate of unplanned revascularisation (6.1% vs 2.6%; HR 2.50, 95% CI: 1.11-5.61; p=0.026). Among the patients, 55 (25.7%) with non-ruptured TCFA and 110 (15.4%) without non-ruptured TCFA exhibited at least one non-culprit plaque rupture. At the 5-year follow-up, the cumulative incidence of non-culprit lesion-related MACE was comparable between patients with and without non-culprit plaque rupture, both in those with (14.8% vs 8.5%; HR 1.70, 95% CI: 0.67-4.33; p=0.263) and without non-ruptured TCFA (5.7% vs 2.5%; HR 2.15, 95% CI: 0.77-6.03; p=0.146; pinteraction=0.277) (Figure 3).

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics of patients with and without non-culprit plaque rupture.

| Variables | Patients with non-culprit plaque rupture (n=165) | Patients without non-culprit plaque rupture (n=765) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.2±10.9 | 56.5±11.5 | 0.077 |

| Male | 127 (77.0) | 579 (75.7) | 0.727 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 25.6±3.2 | 25.0±3.6 | 0.026 |

| Coronary risk factors | |||

| Current smoker | 75 (45.5) | 424 (55.4) | 0.020 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (26.7) | 168 (22.0) | 0.191 |

| Hypertension | 81 (49.1) | 305 (39.9) | 0.029 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 111 (67.3) | 413 (54.0) | 0.002 |

| CKDa | 8 (4.8) | 47 (6.1) | 0.522 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| TC, mg/dL | 196.1±45.0 | 182.9±39.3 | 0.001 |

| TG, mg/dL | 112.5 [79.7-164.8] | 113.4 [79.7-168.3] | 0.046 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 127.6±40.7 | 117.0±33.4 | 0.003 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 48.6±11.1 | 49.3±11.9 | 0.525 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 4.2 [1.9-10.0] | 4.2 [1.9-10.1] | 0.065 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.8 [5.5-6.3] | 5.8 [5.5-6.3] | 0.043 |

| Medication history | |||

| Aspirin | 55 (33.3) | 189 (24.7) | 0.022 |

| P2Y12 receptor inhibitor | 19 (11.5) | 34 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 24 (14.5) | 53 (6.9) | 0.001 |

| Beta blocker | 13 (7.9) | 35 (4.6) | 0.082 |

| ACEi/ARB | 18 (10.9) | 65 (8.5) | 0.324 |

| Discharge medications | |||

| Aspirin | 164 (99.4) | 761 (99.5) | 1.000 |

| P2Y12 receptor inhibitor | 162 (98.2) | 762 (99.6) | 0.124 |

| Statin | 164 (99.4) | 765 (100) | 0.177 |

| Beta blocker | 121 (73.3) | 506 (66.1) | 0.074 |

| ACEi/ARB | 96 (58.2) | 410 (53.6) | 0.283 |

| Values are mean±SD, n (%), or median [interquartile range]. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. aEstimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated by using the 2009 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI: body mass index; CKD: chronic kidney disease; HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SD: standard deviation; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride | |||

Table 2. OCT characteristics in non-culprit lesions (patient level).

| Variables | Patients with non-culprit plaque rupture (n=165) | Patients without non-culprit plaque rupture (n=765) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total length of non-culprit segments analysed, mm | 174.0±34.5 | 168.9±34.5 | 0.083 |

| Number of NCLs | 5.0 [4.0-6.0] | 4.0 [2.0-5.0] | <0.001 |

| Number of plaque ruptures | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | - | NA |

| Other qualitative characteristics | |||

| Non-ruptured TCFA | 55 (33.3) | 159 (20.8) | 0.001 |

| Macrophage | 165 (100) | 677 (88.5) | <0.001 |

| Microchannels | 157 (95.2) | 599 (78.3) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol crystals | 107 (64.8) | 245 (32.0) | <0.001 |

| Layered tissue | 132 (80.0) | 447 (58.4) | <0.001 |

| Calcification | 126 (76.4) | 467 (61.0) | <0.001 |

| Values are mean±SD, median [interquartile range], or n (%). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. NA: not applicable; NCL: non-culprit lesion; OCT: optical coherence tomography; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma | |||

Figure 2. The frequency of non-culprit plaque rupture and non-ruptured TCFA. A) Patient-level analysis (n=930). There were 165 STEMI patients (17.7%) with non-culprit PR and 214 (23.0%) with non-ruptured TCFA. These included 110 patients (11.8%) with only non-culprit PR, 55 (5.9%) with both non-culprit PR and non-ruptured TCFA, and 159 (17.1%) with only non-ruptured TCFA. B) Plaque-level analysis (n=3,660). Within the 3,660 non-culprit plaques, 209 (5.7%) had the PR phenotype, and 281 (7.7%) had the non-ruptured TCFA phenotype. PR: plaque rupture; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma

Figure 3. NCL-related MACE of non-culprit PR. A) NCL-related MACE occurred more frequently in patients with non-culprit PR than in those without. B) Kaplan-Meier curves showed that the NCL-related MACE were similar in NCLs with and without PR. C) Patients with PR and non-ruptured TCFA in non-culprit segments had the highest cumulative event rate. In the subgroup of patients with non-ruptured TCFA, the incidence of NCL-related MACE was comparable between patients with and without non-culprit PR. In the subgroup of patients without non-ruptured TCFA, the incidence of NCL-related MACE was comparable between patients with and without non-culprit plaque rupture. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; NCL: non-culprit lesion; NC: non-culprit; NR: non-ruptured; PR: plaque rupture; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma

Lesion-level analysis

A total of 3,660 non-culprit lesions were identified, among which 209 (5.7%) exhibited plaque rupture and 281 (7.7%) were classified as non-ruptured TCFA (Figure 2). The angiographic and OCT characteristics in non-culprit lesions are presented in Table 3. Non-culprit lesions with plaque rupture were more likely located at the right coronary artery (57.9% vs 38.0%; p<0.001), less likely at the left circumflex artery (13.4% vs 29.5%; p<0.001), and were closer to the coronary ostium (26.4 [IQR 16.3-38.6] mm vs 29.0 [IQR 15.9-44.1] mm; p=0.006), as compared with their counterparts without plaque rupture. In addition, lesions with plaque rupture showed more severe angiographic stenosis, higher lipid content, thinner FCT, and more qualitative OCT features than those without.

A total of 35 evaluable events occurred in non-culprit lesions, comprising 10 non-fatal MIs (i.e., target vessel MI) and 25 unplanned revascularisations (i.e., target lesion revascularisation). These events were identified via baseline OCT and event-matched angiography. All originated from baseline non-culprit lesions without plaque rupture, including eight from non-ruptured TCFAs (three target vessel MIs and five target lesion revascularisations). The cumulative event rate attributable to specific non-culprit lesions with plaque rupture was comparable to that of their counterparts without plaque rupture (Figure 3) (0.0% vs 1.2%; HR 0.05, 95% CI: 0.00-24.68; p=0.336). Specifically, target vessel MI (0.0% vs 0.4%; HR 0.05, 95% CI: 0.00-5475.04; p=0.605) and target lesion revascularisation (0.0% vs 0.8%; HR 0.05, 95% CI: 0.00-80.48; p=0.418) did not differ significantly between lesions with and without plaque rupture (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3. Baseline angiographic and OCT findings in non-culprit lesions (lesion level).

| Variables | Lesions with plaque rupture (n=209) | Lesions without plaque rupture (n=3,451) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion location | |||

| LAD | 60 (28.7) | 1,120 (32.5) | 0.229 |

| LCx | 28 (13.4) | 1,019 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| RCA | 121 (57.9) | 1,312 (38.0) | <0.001 |

| QCA data | |||

| RLD, mm | 3.2 [2.8-3.6] | 3.0 [2.5-3.4] | <0.001 |

| MLD, mm | 2.0 [1.5-2.4] | 2.0 [1.6-2.5] | 0.318 |

| DS, % | 38.0 [27.5-50.0] | 31.0 [22.0-41.0] | <0.001 |

| Lesion length, mm | 15.2 [11.2-22.9] | 13.0 [9.5-17.6] | <0.001 |

| OCT characteristics | |||

| Distance to ostium, mm | 26.4 [16.3-38.6] | 29.0 [15.9-44.1] | 0.006 |

| MLA, mm2 | 3.6 [2.2-5.3] | 3.9 [2.5-5.7] | 0.208 |

| Lipid length, mm | 12.1 [7.7-18.4] | 7.9 [4.7-13.2] | <0.001 |

| Mean lipid arc, ° | 187.8 [149.1-230.9] | 145.2 [117.6-180.0] | <0.001 |

| Minimal FCT, μm | 53.3 [40.0-60.0] | 100.0 [76.7-140.0] | <0.001 |

| Lipid-rich plaque | 206 (98.6) | 2,204 (63.9) | <0.001 |

| Non-ruptured TCFA | 0 (0) | 281 (8.1) | NA |

| Macrophage | 205 (98.1) | 2,920 (84.6) | <0.001 |

| Microchannels | 139 (66.5) | 1,838 (53.3) | 0.001 |

| Cholesterol crystals | 70 (33.5) | 529 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Layered tissue | 95 (45.5) | 1,143 (33.1) | <0.001 |

| Calcification | 94 (45.0) | 1,376 (39.9) | 0.088 |

| Values are n (%) or median [interquartile range]. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. DS: diameter stenosis; FCT: fibrous cap thickness; LAD: left anterior descending artery; LCx: left circumflex artery; MLA: minimal lumen area; MLD: minimal lumen diameter; NA: not applicable; OCT: optical coherence tomography; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography; RCA: right coronary artery; RLD: reference lumen diameter; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma | |||

Prognostic value of non-culprit plaque rupture

The prognostic values of plaque rupture and non-ruptured TCFA for non-culprit lesion-related MACE are presented in Table 4. Complete multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models analysing non-culprit plaque rupture at the patient level are provided in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4. Non-culprit plaque rupture was not significantly associated with non-culprit lesion-related MACE (HR 1.60, 95% CI: 0.76-3.36; p=0.219). After adjusting for non-ruptured TCFA, it was found that non-ruptured TCFA (HR 2.72, 95% CI: 1.37-5.40; p=0.004), but not plaque rupture (HR 1.48, 95% CI: 0.70-3.14; p=0.304), at the non-culprit site was significantly associated with non-culprit lesion-related MACE. These findings were consistent at the lesion level (Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Table 6).

Table 4. Adjusted risk for the presence of non-culprit PR and/or non-ruptured TCFA in multivariable models.

| Variables | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-level models in NCL-related MACEa | ||

| With non-culprit PR introduced | ||

| Non-culprit PR | 1.60 (0.76-3.36) | 0.219 |

| With non-culprit PR and non-ruptured TCFA introduced | ||

| Non-culprit PR | 1.48 (0.70-3.14) | 0.304 |

| Non-ruptured TCFA | 2.72 (1.37-5.40) | 0.004 |

| Lesion-level models in NCL-related MACEb | ||

| With non-culprit PR introduced | ||

| Non-culprit PR | - | 0.967 |

| With non-culprit PR and non-ruptured TCFA introduced | ||

| Non-culprit PR | - | 0.972 |

| Non-ruptured TCFA | 2.72 (1.21-6.11) | 0.016 |

| A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. aCovariates for each patient-level model were the number of NCLs, baseline demographic characteristics (age, sex, BMI), coronary risk factors (current smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, chronic kidney disease), and medication use (aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitor, and statin) before admission and after discharge. bCovariates for each lesion-level model were vessel territory (right coronary artery as reference), distance to coronary ostium, minimal lumen area, and other qualitative OCT features (calcification, macrophage, microchannels, cholesterol crystals, and layered tissue) assessed within the same non-culprit lesion. -: due to the absence of NCLs with PR causing MACE, the HR value was inestimable. BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; NCL: non-culprit lesion; OCT: optical coherence tomography; PR: plaque rupture; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma | ||

Discussion

In this large-scale observational cohort of STEMI patients, we observed that the prevalence of non-culprit plaque rupture was 17.7%, and there was a higher incidence of vulnerable lesion characteristics and MACE in patients with non-culprit plaque rupture compared to in patients without non-culprit plaque rupture. However, multivariable analysis showed no independent association between non-culprit plaque rupture and subsequent adverse events. Importantly, our findings indicate that throughout atherosclerotic disease progression, non-ruptured TCFA − rather than plaque rupture − is an independent predictor of adverse clinical outcomes during long-term follow-up (Central illustration).

Central illustration. The long-term prognosis value of OCT imaging in STEMI patients with non-culprit plaque rupture. A) OCT examinations were conducted on a total of 3,660 untreated NCLs from 930 STEMI patients, with a median follow-up period of 4.08 years (interquartile range 2.96-4.97). Patients and lesions were categorised into groups with and without non-culprit plaque rupture. Furthermore, non-ruptured TCFA was a classification standard in the subgroup. B) STEMI patients in the non-culprit plaque rupture group had worse long-term outcomes (8.9% vs 3.8%, unadjusted HR 2.25, 95% CI: 1.13-4.49). Furthermore, after stratification by the presence or absence of non-ruptured TCFA, non-culprit plaque rupture was not associated with NCL-related MACE. In addition, NCL-related MACE were similar for lesions with versus without plaque rupture (0.0% vs 1.2%, unadjusted HR 0.05, 95% CI: 0.00-24.68). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MACE: major adverse cardiac events; NCL: non-culprit lesion; OCT: optical coherence tomography; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma

Frequency of non-culprit plaque rupture

While coronary plaque rupture with subsequent thrombus formation is recognised as the principal pathophysiological mechanism underlying acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and sudden cardiac death910, not all plaque ruptures cause events. Plaque rupture at non-culprit segments (i.e., subclinical plaque rupture), as an indicator of plaque vulnerability, has received limited attention in natural history studies. Emerging evidence suggests that non-culprit plaque rupture is not an uncommon finding in the coronary tree. Subsequent investigations employing intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) (Hong et al: 17% in 122 acute myocardial infarction [AMI] patients11; Schoenhagen et al: 19% in 105 AMI patients12; Xie et al: 14% in 660 ACS patients with 198 STEMI cases13) and OCT (Kubo et al: 12% in 26 AMI patients14; Fujii et al: 31% in 35 AMI patients15; Vergallo et al: 16% in 107 ACS patients4) reported substantially lower prevalence rates of plaque rupture at non-culprit sites, ranging from 12% to 31% in patients with acute presentations. Notably, these studies were limited by relatively small cohort sizes, particularly regarding STEMI populations. In our large-scale analysis of 930 STEMI patients − the most extensive cohort reported to date − we observed a non-culprit plaque rupture prevalence of 17.7% (165/930), confirming and expanding upon the previously reported range.

Morphological findings of non-culprit plaque rupture

Subclinical plaque rupture represents a systemic manifestation of pancoronary instability, which may precipitate acute thrombotic events through occlusive thrombosis or drive accelerated plaque progression following clinically silent healing processes1617. Our findings extend these observations by demonstrating that patients with non-culprit plaque rupture exhibit a diffuse pancoronary phenotype characterised by high-risk morphological features. At least one non-ruptured TCFA was identified in approximately one-third of STEMI patients with non-culprit plaque rupture. Furthermore, the non-culprit plaque rupture group exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of lipid-rich plaque, microchannels, cholesterol crystals, and layered tissue in both patient- and lesion-level analyses. These findings align with the pancoronary high-risk atherosclerotic phenotype reported by Vergallo et al in ACS patients with non-culprit plaque rupture4. Importantly, these vulnerable characteristics at non-culprit sites emerged as independent predictors of angiographic plaque progression, potentially mediated through cyclical subclinical plaque disruption and healing181920. Similarly, TCFA was the highest-risk plaque phenotype associated with adverse events in many studies282122.

Adverse outcomes of non-culprit plaque rupture

Non-culprit lesions are highly prevalent in the coronary tree and contribute to nearly half of recurrent cardiac ischaemic events2. Multiple prospective natural history studies have demonstrated that high-risk plaque morphology at non-culprit sites correlates with adverse clinical outcomes at both the patient and lesion levels. The PROSPECT study identified TCFA, luminal area, and plaque burden through 3-vessel intravascular imaging2. The PROSPECT II and LRP studies revealed associations between high lipid content (quantified by near-infrared spectroscopy) and clinical risk2324, while the CLIMA study linked lipid arc, FCT, lumen area, and macrophage infiltration (assessed via OCT of the left anterior descending artery) to adverse outcomes21. Additionally, the COMBINE OCT-FFR and PECTUS-obs studies demonstrated that TCFA and predefined high-risk plaque criteria (detected by OCT) predict events in fractional flow reserve-negative lesions722. However, current evidence regarding the long-term prognostic implications of plaque rupture at non-culprit coronary sites remains limited.

Interestingly, we observed that patients with non-culprit plaque rupture had a higher incidence of culprit lesion-related MACE than those without. In fact, non-culprit plaque rupture is more likely to exist in patients with culprit plaque rupture2526, who present different clinical and underlying lesion features9 and show a worse prognosis10 compared with other underlying mechanisms contributing to acute coronary events. In addition, patients in the non-culprit plaque rupture group were older, had a higher incidence of coronary risk factors and serum lipid levels, which may have caused the difference in culprit lesion-related MACE risk between the two groups.

A subanalysis of the PROSPECT study13 observed a tendency for IVUS-defined non-culprit plaque rupture to result in higher rates of non-culprit lesion-related MACE during 3 years of follow-up, although the incidence of adverse events was not different between 660 ACS patients with and without non-culprit plaque rupture. Subsequently, Vergallo et al also found this phenomenon using OCT during 1 year of follow-up in 261 patients with coronary artery disease4. Both studies were limited by the relatively small patient population (especially patients with acute presentation). In the present large-scale study, we found the incidence of non-culprit lesion-related MACE was higher in STEMI patients with non-culprit plaque rupture than their counterparts during 5-year follow-up, and the increased risk of adverse events was mainly due to unplanned revascularisation.

However, non-culprit plaque rupture was not associated with non-culprit lesion-related MACE by multivariable analysis in STEMI patients who underwent 3-vessel OCT examination. All non-culprit lesion-related clinical events that occurred during follow-up originated from baseline lesions without plaque rupture. Reduced lipid burden and the rupture healing process partially account for this phenomenon. Fibrous cap disruption with subsequent thrombus development may reduce lipid burden by releasing lipid content. During this process, subclinical plaque rupture tended to heal, forming a layered structure and reaching a stable stage27. In the current study, non-culprit lesions with plaque rupture were more likely to show a layered phenotype than those with non-ruptured TCFA (Supplementary Table 7) (45.5% vs 35.6%; p=0.022). This result again supports the notion that disruption of plaque and the healing process lead to lesion stabilisation (especially when compared to non-ruptured TCFAs). Of note, Volleberg et al5 found that non-culprit plaque rupture was associated with 2-year adverse events in AMI patients undergoing OCT of all fractional flow reserve-negative intermediate non-culprit lesions. Due to the presence of plaque rupture and/or thrombus, only those cases were included in the predefined high-risk criteria of PECTUS-obs study7 and not in earlier natural history studies. Hence, the findings of Volleberg et al need further verification.

Clinical value of non-ruptured TCFA

As mentioned above, extensive prior investigations have proved TCFA to be a high-risk plaque phenotype strongly correlated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Our study advances this finding by demonstrating distinct prognostic implications between non-ruptured TCFA and ruptured TCFA (i.e., plaque rupture) at non-culprit lesions. The present study found that non-ruptured TCFA, not plaque rupture, at the non-culprit sites was associated with long-term adverse events.

The conceptual framework identifying TCFA as a precursor to plaque rupture stems from the hypothesis that prerupture atherosclerotic lesions share key morphological features with ruptured plaques, differing primarily by an intact fibrous cap62728. TCFAs, commonly detected at multiple coronary sites in sudden death due to plaque rupture, are defined by necrotic cores with overlying fibrous caps <65 μm2728. Seminal pathological studies identified TCFAs at non-culprit coronary sites in approximately 70% of acute plaque rupture fatalities, contrasting with their markedly reduced occurrence (30%) in sudden cardiac death cases secondary to plaque erosion2729. Vergallo et al, by 3-vessel OCT imaging, confirmed these findings in vivo, demonstrating that TCFAs preferentially cluster in the non-culprit segments of ACS patients caused by plaque rupture25 and that this was an independent morphological predictor of multiple plaque ruptures4.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the retrospective design of this study inherently carries the risk of selection bias. While 3-vessel OCT imaging in STEMI patients was rigorously attempted, some constraints − including clinical contraindications (e.g., cardiogenic shock, severe kidney disease) or unfavourable coronary anatomy (e.g., chronic total occlusions, extremely tortuous vessels) − may have influenced operator decisions regarding OCT feasibility. Therefore, the conclusion might not be generalisable to all STEMI patients. Second, although all three major epicardial arteries underwent comprehensive OCT interrogation, distal small vessel segments and side branches were not systematically analysed because of technical limitations inherent to current OCT imaging catheters. Third, the FCT measurement may be limited by the subjectivity of visual identification of the thinnest point and manual measurement. However, strong interobserver (κ=0.86) and intraobserver (κ=0.92) agreement for TCFA identification were observed in this study. Fourth, the higher number of non-culprit lesions analysed per patient in the plaque rupture group may have influenced the incidence of non-culprit lesion-related MACE. Although we adjusted for this variable in multivariable analyses, residual confounding cannot be entirely ruled out. Fifth, the presence of thrombus within the lumen may compromise the accurate assessment of underlying plaque morphology in certain cases, due to the attenuation of the OCT light signal by red blood cells. Finally, the number of non-culprit lesion-related MACE (especially hard endpoints such as cardiac death or non-fatal MI) in this study was low, and the study was not powered to assess differences in individual event components. Among these, only the difference in unplanned revascularisation was statistically significant between patients with and without non-culprit plaque rupture.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the presence of OCT-identified non-ruptured TCFA in non-culprit coronary segments is independently associated with both patient- and lesion-related adverse clinical outcomes in STEMI patients. Furthermore, patients with non-culprit plaque rupture demonstrate a pancoronary high-risk atherosclerotic phenotype and exhibit an elevated risk of long-term adverse clinical events, primarily attributable to the contributions of non-ruptured TCFA. These findings underscore the prognostic significance of non-ruptured TCFA in risk stratification, lending robust support to high-risk patients and vulnerable plaque hypotheses.

Impact on daily practice

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with non-culprit plaque rupture demonstrate a pancoronary high-risk atherosclerotic phenotype and exhibit an elevated risk of long-term adverse clinical events. Throughout atherosclerotic disease progression, non-ruptured thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) − rather than plaque rupture − is the independent predictor of adverse clinical outcomes during long-term follow-up. These findings underscore the prognostic significance of non-ruptured TCFA in risk stratification, lending robust support to high-risk patients and vulnerable plaque hypotheses.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the colleagues and patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 62135002 to Dr Yu, 82322036 and 82072091 to Dr Dai, 82202286 to Dr Fang), and the Fund of Key Laboratory of Myocardial Ischemia, Ministry of Education (KF202401 to Dr Zhao).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.