Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

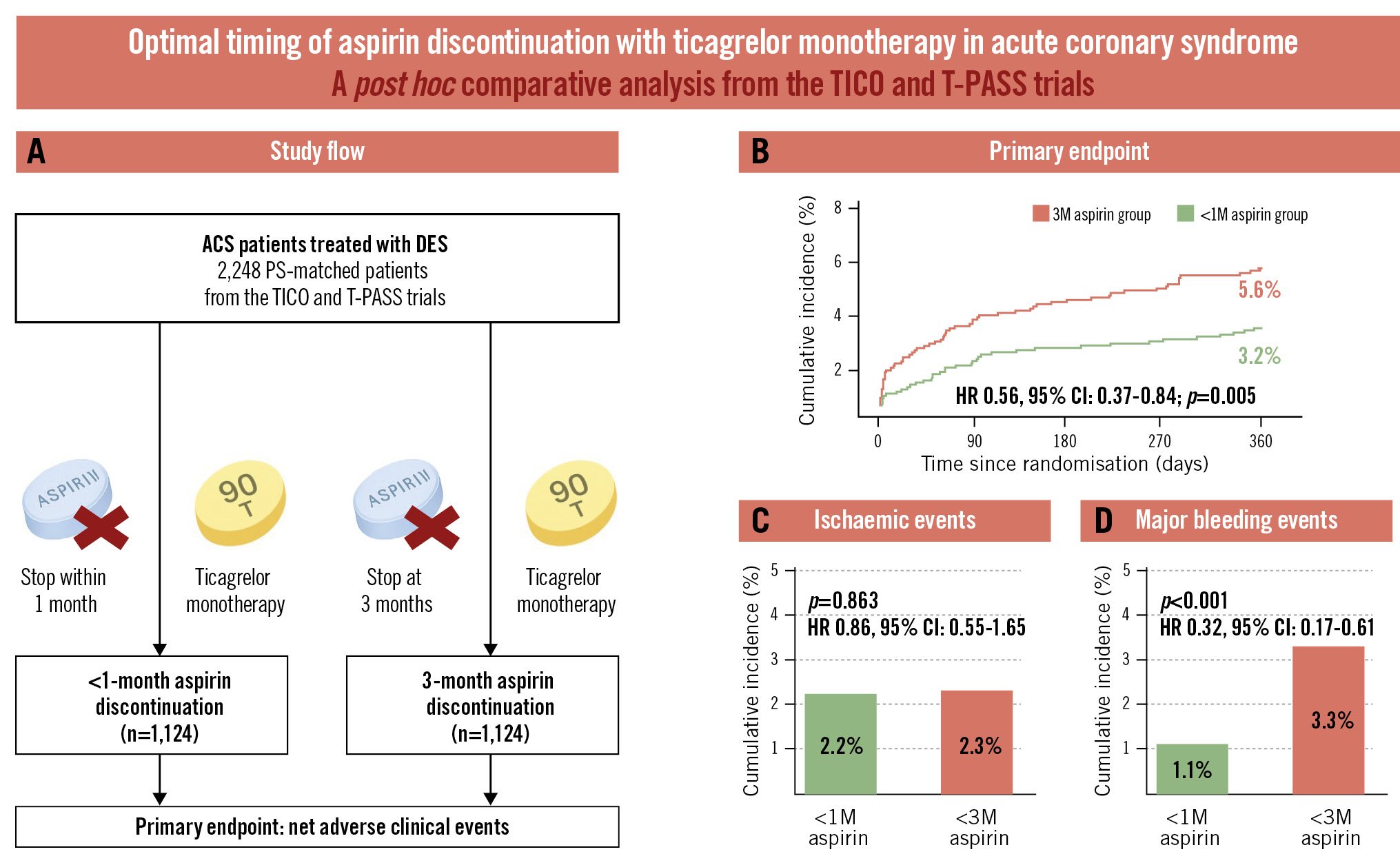

Background: Ticagrelor monotherapy following abbreviated dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is an emerging strategy for patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, the timing of aspirin discontinuation has not been directly compared in this setting.

Aims: We aimed to compare the clinical outcomes of aspirin discontinuation within 1 month versus at 3 months after PCI in patients with ACS.

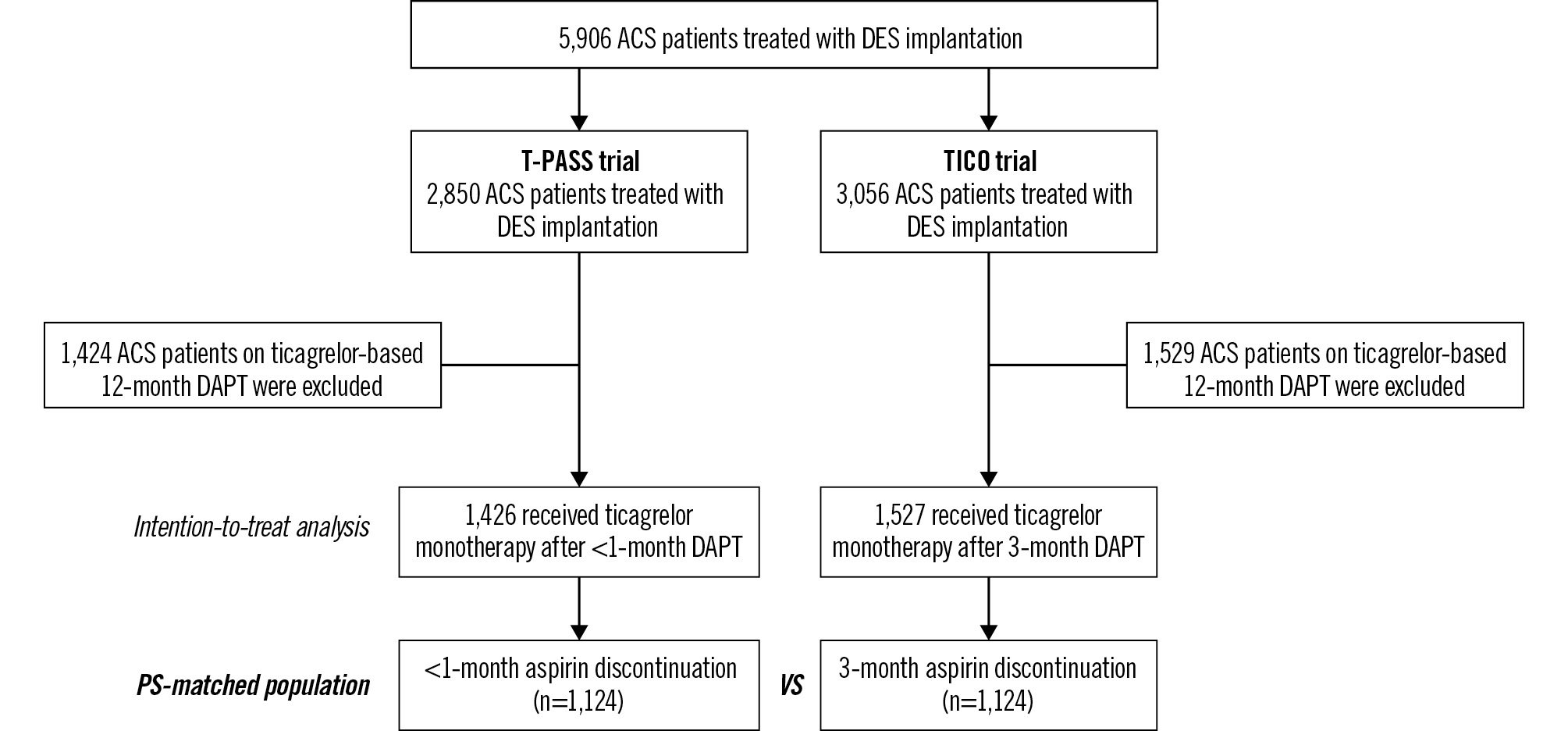

Methods: This post hoc analysis used individual patient-level data from the TICO and T-PASS trials, which exclusively enrolled patients with ACS undergoing PCI. Of 2,953 patients who received ticagrelor monotherapy after abbreviated DAPT, 1,426 discontinued aspirin within 1 month and 1,527 at 3 months. After propensity score matching, 2,248 patients were included in the final analysis. The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation, stroke, and major bleeding at 1 year.

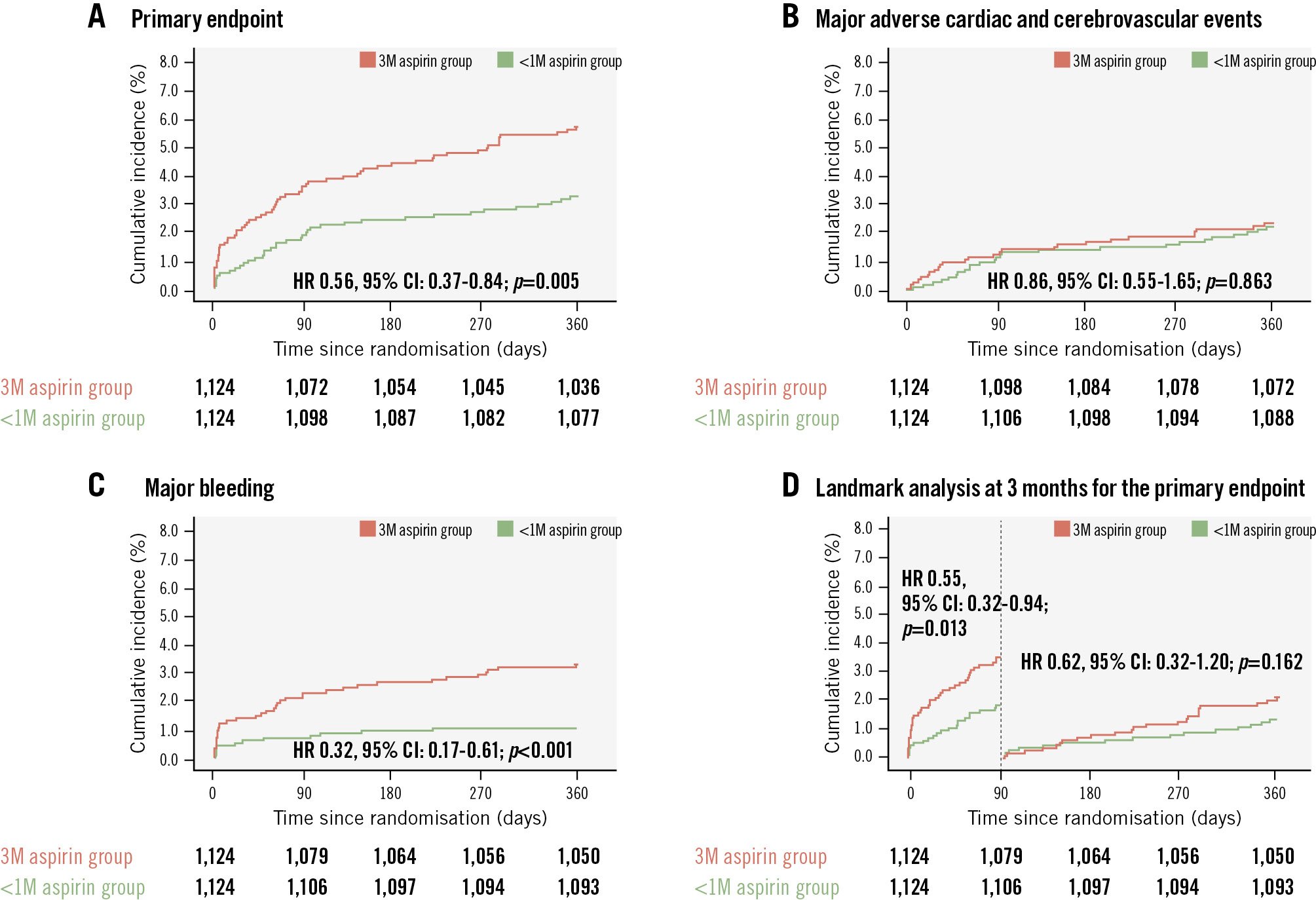

Results: The primary endpoint occurred less frequently in the <1-month group than in the 3-month group (3.2% vs 5.6%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.37-0.84; p=0.005). Ischaemic event rates were comparable (2.2% vs 2.3%; HR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.55-1.65; p=0.863), whereas major bleeding was significantly lower in the <1-month group (1.1% vs 3.3%; HR 0.32, 95% CI: 0.17-0.61; p<0.001). Landmark analysis showed that event rates diverged primarily within the first 90 days, with no significant heterogeneity between the early and late periods.

Conclusions: Aspirin discontinuation within 1 month followed by ticagrelor monotherapy improved net clinical outcomes compared with 3-month discontinuation, primarily by reducing major bleeding without increasing ischaemic risk. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02494895 (TICO), NCT03797651 (T-PASS).

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), a combination of aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors, is essential for managing patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Compared with clopidogrel-based DAPT, a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor, such as prasugrel or ticagrelor, provides stronger and more consistent platelet inhibition, resulting in improved clinical outcomes in these patients12. Current ACS guidelines recommend a potent P2Y12 inhibitor over clopidogrel for at least 12 months following PCI with drug-eluting stents (DES)34. However, these strategies may be accompanied by an increased risk of bleeding, a complication associated with poor clinical outcomes56.

To optimise the balance between ischaemic and bleeding risks, several randomised clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy and safety of an aspirin-discontinuation strategy followed by ticagrelor monotherapy78910. Among these, the Ticagrelor Monotherapy After 3 Months in the Patients Treated With New Generation Sirolimus Stent for Acute Coronary Syndrome (TICO) and Ticagrelor Monotherapy in PAtients Treated With New-generation Drug-eluting Stents for Acute Coronary Syndrome (T-PASS) trials exclusively enrolled patients with ACS treated with DES and demonstrated the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor monotherapy following abbreviated DAPT910. In accordance with these findings, the most recent American guidelines provide a Class I recommendation for ticagrelor monotherapy after 1-3 months of DAPT in patients with ACS to reduce bleeding risk11. However, the optimal timing of aspirin discontinuation, specifically within 1 month versus at 3 months, has not been evaluated in these patients. Therefore, we aimed to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of aspirin discontinuation within 1 month versus at 3 months after PCI with subsequent ticagrelor monotherapy in patients with ACS, using individual patient data from the TICO and T-PASS trials.

Methods

Study population and procedures

We performed a post hoc comparative analysis using merged datasets from the TICO and T-PASS trials. Although both trials were randomised, the present analysis was observational in nature and excluded patients assigned to the conventional 12-month DAPT regimen. After merging the datasets and excluding patients on the 12-month DAPT regimen, a total of 2,953 patients with ACS who received ticagrelor monotherapy after abbreviated DAPT were identified. The <1-month group (n=1,426) was derived from the T-PASS trial, whereas the 3-month group (n=1,527) was derived from the TICO trial. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process for the study population.

The TICO trial, an investigator-initiated, multicentre, randomised, unblinded trial conducted at 38 centres in the Republic of Korea, enrolled 3,056 patients who underwent PCI for ACS9. After successful PCI, patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to conventional ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT or aspirin discontinuation at 3 months followed by ticagrelor monotherapy9. A total of 1,527 patients were assigned to the 3-month aspirin discontinuation group between August 2015 and October 2018, with 1,339 patients (88%) compliant with the assigned treatment. Similarly, the T-PASS trial was conducted at 24 centres in the Republic of Korea and included a total of 2,850 patients with ACS10. In this trial, patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT or aspirin discontinuation within 1 month after DES implantation between April 2019 and May 2022. A total of 1,426 patients were assigned to the <1-month group, and discontinuation occurred after a median of 16 days (interquartile range [IQR] 12-25 days). Of these, 1,221 patients (86%) adhered to the assigned treatment protocol, with no significant differences in the adherence rates between the groups. The reasons for non-compliance have been detailed in previous reports910. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria of the two trials are summarised in Supplementary Table 1.

In both trials, PCI was performed using bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stents (Orsiro [Biotronik]) and standard techniques. At the time of index PCI, loading doses of aspirin (300 mg) and ticagrelor (180 mg) were administered if the patient was not already taking these drugs. Thereafter, ticagrelor was prescribed at a maintenance dose of 90 mg twice daily according to the study protocol. The study population was not permitted to use concomitant antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants. Other cardiovascular medications, such as lipid-lowering or antihypertensive therapies, were administered according to current guidelines.

Figure 1. The selection process of the study population. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DES: drug-eluting stent; PS: propensity score; T-PASS: Ticagrelor Monotherapy in PAtients Treated With New-generation Drug-eluting Stents for Acute Coronary Syndrome; TICO: Ticagrelor Monotherapy After 3 Months in the Patients Treated With New Generation Sirolimus Stent for Acute Coronary Syndrome

Study endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint was net adverse clinical events, defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation, stroke, and major bleeding within 1 year. Post-discharge myocardial infarction was identified by ischaemic symptoms, electrocardiographic changes, or imaging findings combined with elevated cardiac biomarkers exceeding the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit12. Stent thrombosis was defined as definite or probable events based on the Academic Research Consortium definitions13. Ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation was defined as repeat PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting for a target vessel with >50% stenosis and evidence of myocardial ischaemia, including clinical symptoms or a positive stress test14. Stroke was characterised as the presence of acute neurological symptoms confirmed by brain imaging14. Major bleeding events were defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium Type 3 or 5 bleeding15.

Secondary endpoints included the individual components of the primary endpoint as well as major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, which were defined as a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation, and stroke.

Statistical analysis

The intention-to-treat principle was implemented based on the initial randomisation groups to analyse individual patient data. Categorical variables are presented as n (%) and were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation or median (IQR) and were analysed using Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, depending on the distribution of the data.

Propensity score matching was used to construct a balanced 1:1 matched cohort between the <1-month and 3-month groups. Propensity scores were calculated using multivariable logistic regression analysis incorporating baseline clinical, lesion, and procedural variables. Patients were matched using nearest-neighbour matching without replacement and a calliper width of 0.03. Standardised mean differences <10% were used to confirm balance across covariates after matching. Model calibration and discrimination were assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and Harrell’s C-index16.

In the propensity score-matched population, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed to estimate event rates, and differences in event-free survival were compared using the log-rank test. A prespecified 3-month landmark analysis was conducted because antiplatelet regimens differed between the groups during the first 3 months (aspirin discontinuation within 1 month vs continued ticagrelor-based DAPT) and became identical thereafter (ticagrelor monotherapy). Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to identify independent predictors of the primary endpoint in the propensity score-matched population, and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. Variables with p-values<0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable model. Subgroup analyses were performed based on prespecified factors, including age, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, clinical presentation, presence of multivessel disease, total stent length, and vascular access. Adjusted HRs were calculated using multivariable Cox regression analysis, incorporating clinical and procedural variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 26.0 (IBM) and R, version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

The baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics of the overall population are shown in Supplementary Table 2. After propensity score matching, 1,124 patients were included in each group, and the groups were well balanced across clinical, lesion, and procedural variables (Table 1). In the propensity score-matched population, aspirin was discontinued at a median of 16 days (IQR 12-25) after PCI in the <1-month group. The mean age of the cohort was 60.4 years, and approximately 81.0% of patients were male. Overall, across both groups, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus were 48.6% and 27.3%, respectively, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction accounted for 38.6% of the clinical presentations.

The 1-year clinical outcomes of the propensity score-matched population are summarised in Table 2. The median follow-up duration was 365 days for both groups. The primary endpoint occurred less frequently in the <1-month group than in the 3-month group (3.2% vs 5.6%; HR 0.56, 95% CI: 0.37-0.84; p=0.005) (Figure 2A). The incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events was similar between the two groups (2.2% vs 2.3%; HR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.55-1.65; p=0.863) (Figure 2B), whereas the rate of major bleeding was significantly lower in the <1-month group than in the 3-month group over 12 months (1.1% vs 3.3%; HR 0.32, 95% CI: 0.17-0.61; p<0.001) (Figure 2C). When comparing the groups in the 3-month landmark analysis, the primary event rates diverged within the first 90 days (HR 0.55, 95% CI: 0.32-0.94; p=0.013) (Figure 2D). However, the interaction p-value (p=0.79) indicated no significant heterogeneity in the treatment effect between the early and late periods. When assessing the overall unmatched population, the results were consistent with the matched analysis and are summarised in Supplementary Table 3.

In the univariate analysis, conventional risk factors, including age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and low body mass index, were associated with an increased incidence of the primary endpoint events (Table 3). A history of coronary bypass surgery, transfemoral approach, or left main disease was also associated with a higher incidence of the primary endpoint. In contrast, discontinuation of aspirin within 1 month had a protective effect against the occurrence of the primary endpoint. After covariate adjustment, discontinuing aspirin within 1 month remained an independent protective factor against the primary endpoint (HR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.38-0.86; p=0.007).

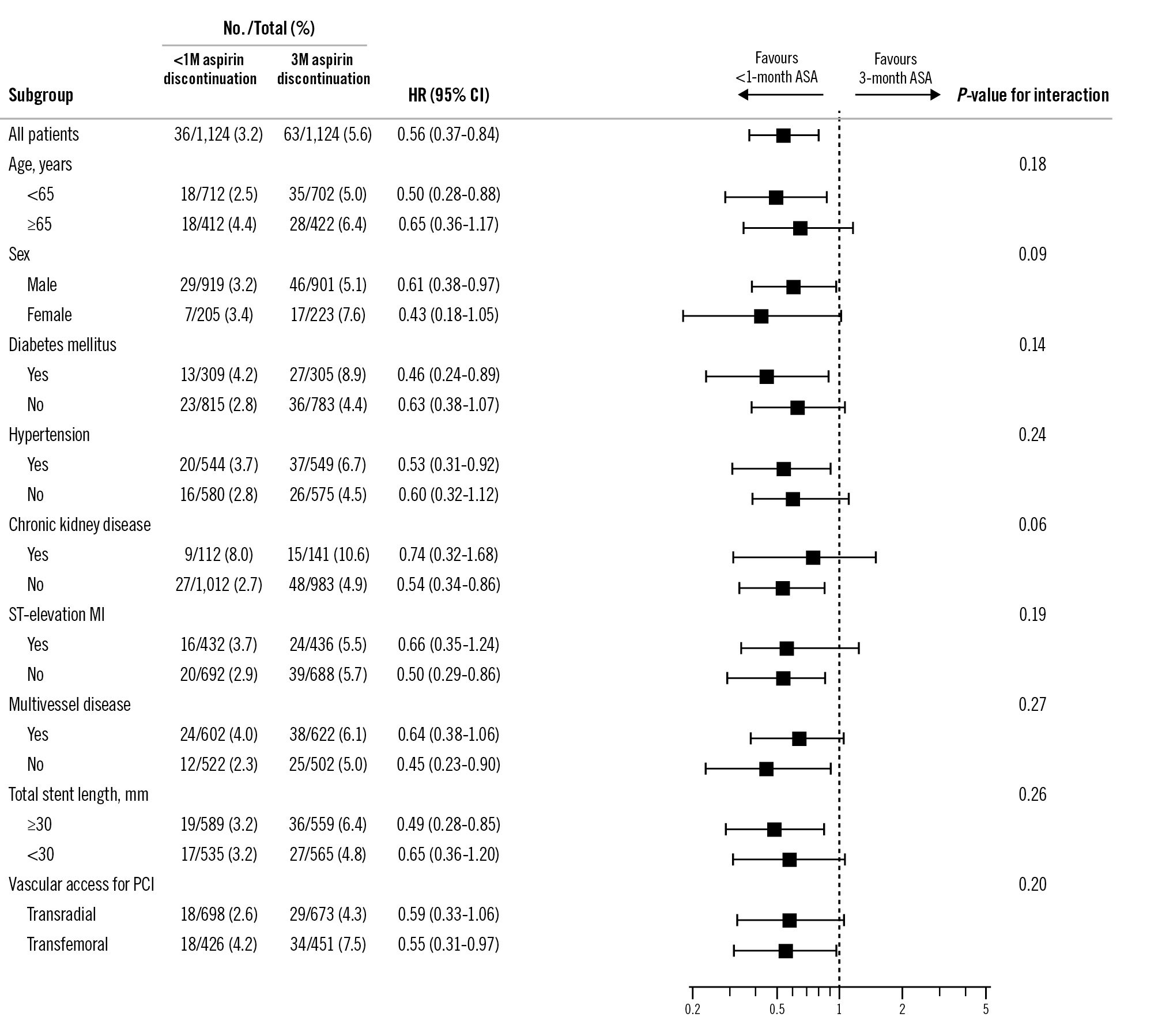

Figure 3 shows the subgroup analyses of the primary endpoint. The effect of aspirin discontinuation within 1 month versus at 3 months appeared consistent across clinically relevant subgroups. However, the number of events within each subgroup was limited, and these analyses should be considered exploratory.

Table 1. Clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics in the propensity score-matched population.

| <1-month aspirin discontinuationa (n=1,124) | 3-month aspirin discontinuation (n=1,124) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.4±10.6 | 60.4±10.8 | 0.939 |

| Male | 919 (81.8) | 901 (80.2) | 0.334 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.0±3.4 | 24.9±3.2 | 0.654 |

| Hypertension | 544 (48.4) | 549 (48.8) | 0.833 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 309 (27.5) | 305 (27.1) | 0.850 |

| Diabetes mellitus with insulin | 31 (2.8) | 32 (2.8) | 0.898 |

| Chronic kidney diseaseb | 112 (10.0) | 141 (12.5) | 0.053 |

| End-stage kidney disease on dialysis | 6 (0.5) | 10 (0.9) | 0.316 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 768 (68.3) | 751 (66.8) | 0.444 |

| Current smoker | 428 (38.1) | 434 (38.6) | 0.795 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 27 (2.4) | 28 (2.5) | 0.891 |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 83 (7.4) | 93 (8.3) | 0.432 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 0.479 |

| Prior stroke | 39 (3.5) | 40 (3.6) | 0.909 |

| Clinical presentation | 0.661 | ||

| Unstable angina | 295 (26.2) | 277 (24.6) | |

| Non-ST-segment elevation MI | 397 (35.3) | 411 (36.6) | |

| ST-segment elevation MI | 432 (38.4) | 436 (38.8) | |

| Transradial approach | 698 (62.1) | 673 (59.9) | 0.280 |

| Use of IABP | 13 (1.2) | 14 (1.2) | 0.846 |

| Use of ECMO | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.4) | 0.705 |

| Multivessel disease | 602 (53.6) | 622 (55.3) | 0.397 |

| Left main disease | 23 (2.0) | 22 (2.0) | 0.880 |

| Bifurcation disease | 174 (15.5) | 169 (15.0) | 0.769 |

| Use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 72 (6.4) | 83 (7.4) | 0.360 |

| Use of thrombectomy | 59 (5.2) | 53 (4.7) | 0.561 |

| Multilesion intervention | 232 (20.6) | 221 (19.7) | 0.563 |

| Multivessel intervention | 185 (16.5) | 179 (15.9) | 0.731 |

| Treated lesions per patient | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 0.595 |

| Total number of stents per patient | 1.0 [1.0-2.0] | 1.0 [1.0-2.0] | 0.724 |

| Total stent length per patient, mm | 30.0 [22.0-41.0] | 26 [22.0-40.0] | 0.099 |

| Data are reported as N (%), mean±standard deviation, or median [IQR]. aAspirin was discontinued after a median of 16 days [IQR 12-25] in the <1-month group. bChronic kidney disease was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 of body surface area. ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; IQR: interquartile range; MI: myocardial infarction | |||

Table 2. Clinical outcomes at 1 year in the propensity score-matched population.

| <1-month aspirin discontinuation (n=1,124) | 3-month aspirin discontinuation (n=1,124) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | ||||

| Net adverse clinical eventsa | 36 (3.2) | 63 (5.6) | 0.56 (0.37-0.84) | 0.005 |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||

| Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular eventsb | 25 (2.2) | 26 (2.3) | 0.86 (0.55-1.65) | 0.863 |

| Major bleedingc | 12 (1.1) | 37 (3.3) | 0.32 (0.17-0.61) | <0.001 |

| BARC Type 3 | 12 (1.1) | 37 (3.3) | 0.32 (0.17-0.61) | <0.001 |

| BARC Type 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | – |

| Cardiac death, myocardial infarction, or stroke | 13 (1.2) | 17 (1.5) | 0.84 (0.50-1.41) | 0.453 |

| All-cause death | 8 (0.7) | 12 (1.1) | 1.00 (0.48-2.10) | 0.361 |

| Cardiac death | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.5) | 0.67 (0.24-1.88) | 0.058 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) | 0.88 (0.32-2.41) | 0.534 |

| Stent thrombosis | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 1.00 (0.14-7.09) | 0.412 |

| Subacute | 2 | 4 | - | |

| Late | 0 | 0 | - | |

| Stroke | 6 (0.5) | 7 (0.6) | 0.73 (0.29-1.81) | 0.768 |

| Ischaemic | 6 | 5 | - | |

| Haemorrhagic | 0 | 2 | - | |

| Ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation | 8 (0.7) | 4 (0.4) | 0.61 (0.29-1.29) | 0.256 |

| Data are presented for the intention-to-treat population and the number of patients with event(s) (% are Kaplan-Meier estimates at day 360). aNet adverse clinical events included the composite of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events and major bleeding. bMajor adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events included the composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation, and stroke. cMajor bleeding included the composite of BARC Types 3 and 5. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio | ||||

Figure 2. Time-to-event curves for each clinical outcome in the propensity score-matched population. A) The <1-month aspirin discontinuation group showed a lower incidence of the primary endpoint (net adverse clinical events, defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation, stroke, and major bleeding) than the 3-month discontinuation group. B) MACCE was defined as a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation, and stroke; MACCE rates were similar between the groups. C) Major bleeding, defined as BARC Type 3 or 5, was significantly lower in the <1-month aspirin discontinuation group compared with the 3-month group. D) A 3-month landmark analysis demonstrated that the excess risk in the 3-month group was confined to the first 90 days, whereas event rates between days 91 and 360 were not significantly different between the groups. 1M: 1 month; 3M: 3 months; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events

Table 3. Predictors for the 1-year primary endpoint in the propensity score-matched population.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age, years | 1.021 (1.002-1.041) | 0.030 | 1.000 (0.979-1.022) | 0.979 |

| Male | 1.370 (0.865-2.170) | 0.179 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.881 (0.825-0.942) | <0.001 | 0.879 (0.979-1.022) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.444 (0.969-2.151) | 0.071 | 1.326 (0.867-2.028) | 0.193 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.835 (1.228-2.741) | 0.003 | 1.534 (1.000-2.355) | 0.049 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.615 (1.652-4.142) | <0.001 | 1.883 (1.125-3.151) | 0.016 |

| End-stage kidney disease on dialysis | 4.780 (1.515-15.084) | 0.008 | 1.084 (0.298-3.943) | 0.903 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 0.832 (0.552-1.253) | 0.378 | ||

| Current smoker | 0.766 (0.503-1.168) | 0.216 | ||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1.259 (0.399-3.972) | 0.695 | ||

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 1.322 (0.688-2.542) | 0.403 | ||

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 6.640 (1.637-26.931) | 0.008 | 3.168 (0.749-13.399) | 0.117 |

| Prior stroke | 0.856 (0.271-2.702) | 0.791 | ||

| Admission via emergency department | 1.161 (0.733-1.838) | 0.525 | ||

| Acute MI presentation | 1.137 (0.713-1.813) | 0.589 | ||

| Transfemoral approach | 1.759 (1.186-2.610) | 0.005 | 1.669 (1.117-2.492) | 0.012 |

| Multivessel disease | 1.407 (0.936-2.113) | 0.101 | ||

| Left main disease | 3.225 (1.412-7.362) | 0.005 | 2.746 (1.156-6.523) | 0.022 |

| Bifurcation disease | 0.995 (0.515-1.724) | 0.986 | ||

| <1-month aspirin discontinuationa | 0.560 (0.372-0.844) | 0.006 | 0.569 (0.377-0.857) | 0.007 |

| a3-month aspirin discontinuation as the reference. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MI: myocardial infarction | ||||

Figure 3. Subgroup analyses for the primary endpoint in the propensity score-matched population. 1M: 1 month; 3M: 3 months; ASA: acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin); CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Discussion

This study directly compared two aspirin discontinuation strategies (<1 month vs at 3 months) using individual patient data from two clinical trials. The main findings were as follows: (1) discontinuing aspirin within 1 month after PCI demonstrated superior net clinical benefits compared with discontinuation at 3 months; (2) the reduction in net clinical adverse events was primarily driven by a lower incidence of major bleeding, and ischaemic event rates were comparable between the groups; (3) the 3-month landmark analysis showed that events occurred more frequently during the first 90 days in the 3-month group, without significant heterogeneity between the early and late periods; and (4) discontinuing aspirin within 1 month was identified as an independent protective factor against the occurrence of the primary endpoint. The overall study design and main findings are summarised in the Central illustration.

Our findings provide insights into the optimal timing of aspirin discontinuation after short-term DAPT in patients with ACS. The benefits of the shorter duration of aspirin (<1 month) combined with ticagrelor monotherapy may be attributable to the increased bleeding risk associated with the concomitant use of aspirin and ticagrelor. Notably, ticagrelor inhibits thromboxane pathways, potentially diminishing the incremental antiplatelet effect of aspirin17. However, the optimal duration of concomitant aspirin use with potent P2Y12 inhibitors remains uncertain.

In our 3-month landmark analysis, the direction of effect for both major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events and major bleeding was consistently unfavourable for the 3-month group across both periods, with statistically significant excess risk confined to the first 90 days. This finding aligns with the biological plausibility that the concomitant use of aspirin and ticagrelor confers an increased risk of bleeding during the early treatment phase. In contrast, the transition to ticagrelor monotherapy attenuates this excess risk. Although the interaction testing was underpowered and the relatively small number of events limited the precision of our estimates, the absence of a significant interaction supports the overall consistency of the treatment effect across time periods.

Our study provides evidence to inform the optimal duration of aspirin therapy in combination with a potent P2Y12 inhibitor, balancing ischaemic and bleeding risks. Several randomised trials have proposed similar objectives, investigating the efficacy and safety of reduced durations of potent P2Y12 inhibitor-based DAPT and P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy in patients with ACS18192021. In particular, the Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Followed by Monotherapy Instead of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in the Setting of Acute Coronary Syndromes (NEO-MINDSET) and Less Bleeding by Omitting Aspirin in non-ST-segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients (LEGACY) trials are designed to evaluate the impact of immediate aspirin discontinuation1920, whereas the Evaluation of a Modified Anti-Platelet Therapy Associated With Low-dose DES Firehawk in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Treated With Complete Revascularization Strategy (TARGET-FIRST) trial aimed to assess P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy after 1-month DAPT21. Moreover, beyond the early post-PCI phase, a recent individual patient data meta-analysis demonstrated that P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy was superior to aspirin monotherapy for long-term secondary prevention after PCI22. These findings reinforce the broader clinical relevance of P2Y12 inhibitor-based strategies across both early and late phases of secondary prevention.

In our analysis, compared with the 3-month group, the lower incidence of major bleeding in the <1-month group was the driving factor for the reduction in net clinical adverse events. Major bleeding events during the acute phase of ACS treatment significantly increase the risk of mortality. These events are associated with haemodynamic instability or shock, which can lead to myocardial ischaemia23. Furthermore, red blood cell transfusions may increase platelet activation and aggregation24. In this context, the following DAPT de-escalation strategies have recently emerged to achieve an optimal balance between ischaemic and bleeding risk: (1) switching from a potent P2Y12 inhibitor to a less potent one2526, (2) reducing the dose of prasugrel or ticagrelor27, and (3) discontinuing one of the two antiplatelet agents. Among these strategies, the TICO and T-PASS trials evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of aspirin discontinuation in an abbreviated ticagrelor-based DAPT in patients with ACS910.

Our study is consistent with previous research showing that abbreviated aspirin therapy followed by ticagrelor monotherapy reduces bleeding events and improves net clinical outcomes. Prespecified subgroup analyses from randomised clinical trials on ticagrelor monotherapy for the treatment of ACS have consistently shown a significant reduction in major bleeding without an increase in ischaemic risk2829. Similarly, a patient-level meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials in patients with ACS suggested that short-term DAPT was associated with reduced major bleeding without an increase in ischaemic events30. The TARGET-FIRST trial demonstrated that at least 1 month of DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy reduced bleeding risk without increasing ischaemic event rates31, whereas the NEO-MINDSET trial found that immediate aspirin discontinuation may be harmful in terms of ischaemic risk32. Taken together with our findings, these recent study results suggest that a short duration of aspirin therapy plays an important role in balancing bleeding and ischaemic risks.

As the duration of DAPT has been shortened to reduce bleeding complications, concerns have emerged regarding recurrent ischaemic events, including stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction, especially in patients presenting with ACS. The Smart Angioplasty Research Team: Safety of Six-Month Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes (SMART-DATE) trial indicated that a 6-month DAPT duration was associated with a higher risk of myocardial infarction than the standard 12-month duration in patients with ACS33. However, this trial predominantly used clopidogrel (80.8%) instead of a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor, such as prasugrel or ticagrelor, as recommended in the current ACS guidelines.

The Short and Optimal Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Everolimus-Eluting Cobalt-Chromium Stent-3 (STOPDAPT-3) trial investigated an aspirin-free strategy using low-dose prasugrel initiated immediately after PCI34. This approach was associated with increased ischaemic events and failed to reduce bleeding risk, suggesting that aspirin may still play a protective role during the immediate periprocedural period. In this context, our study holds clinical significance by evaluating the efficacy and safety of different aspirin discontinuation durations, while maintaining a consistent ticagrelor-based antiplatelet strategy. Our findings suggest that early aspirin discontinuation with ticagrelor monotherapy may offer a favourable balance between bleeding and ischaemic risks in patients with ACS undergoing PCI.

A recent individual patient data meta-analysis that included the TICO and T-PASS trials compared ticagrelor monotherapy after short-term DAPT with conventional 12-month DAPT35. The study demonstrated that de-escalation to ticagrelor monotherapy reduced major bleeding without increasing ischaemic risk. However, in a prespecified subgroup analysis, the timing of aspirin discontinuation (≤30 vs >30 days) was not associated with differences in clinical outcomes35. In contrast, our study directly compared <1-month and 3-month discontinuation strategies and identified a significant difference in bleeding risk. These divergent findings highlight the need for prospective randomised trials specifically designed to determine the optimal timing of aspirin withdrawal in patients with ACS undergoing PCI.

Central illustration. Aspirin discontinuation within 1 month versus at 3 months with ticagrelor monotherapy in acute coronary syndrome. A) Study flow. Cumulative incidences of the primary endpoint (B), ischaemic events (C), and major bleeding events (D). 1M: 1 month; 3M: 3 months; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; DES: drug-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; PS: propensity score; T-PASS: Ticagrelor Monotherapy in PAtients Treated With New-generation Drug-eluting Stents for Acute Coronary Syndrome; TICO: Ticagrelor Monotherapy After 3 Months in the Patients Treated With New Generation Sirolimus Stent for Acute Coronary Syndrome

Limitations

Our study had certain limitations. First, although the study used individual patient-level data from two randomised trials, the comparison between <1-month and 3-month aspirin discontinuation was post hoc, cross-trial, and observational, without randomisation. Propensity score matching was performed to minimise the influence of baseline differences; however, residual confounding is inevitable, and the results should be interpreted with caution. International guidelines at the time these trials were initiated recommended 12 months of DAPT with aspirin and a potent P2Y12 inhibitor as the standard of care for ACS. Thus, our pooled analysis provides important indirect evidence, and a dedicated randomised trial directly comparing <1-month versus 3-month discontinuation strategies is warranted. Second, as a post hoc pooled analysis of individual patient data from previous trials, differences in baseline characteristics were observed because of the different periods in which the trials were conducted. In addition, within the <1-month group, the actual timing of aspirin discontinuation varied throughout the first month. This variability may have introduced heterogeneity, limiting the precision of the treatment effect. Third, both the TICO and T-PASS trials were conducted in the Republic of Korea, which limits the generalisability of our findings to Western populations. East Asian populations may exhibit different ischaemic and bleeding tendencies than Caucasian populations; consequently, our results should be confirmed in Western populations. Fourth, we only extended follow-up to 1 year, which may not reflect long-term clinical outcomes. Lastly, these trials exclusively included patients who received biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting stents, potentially limiting the applicability of our findings to patients treated with other types of stents.

Conclusions

Aspirin discontinuation within 1 month after PCI, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy, demonstrated superior net clinical benefits compared with discontinuation at 3 months. These benefits were primarily driven by a significant reduction in major bleeding, without an increase in ischaemic events. Therefore, aspirin discontinuation within 1 month followed by ticagrelor monotherapy may be considered a feasible strategy in patients with ACS treated with DES.

Impact on daily practice

In patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, aspirin discontinuation within 1 month followed by ticagrelor monotherapy was associated with fewer net clinical adverse events compared with 3-month discontinuation. This benefit was primarily driven by a significant reduction in major bleeding without an increase in ischaemic complications. These findings add to the growing evidence supporting abbreviated ticagrelor-based dual antiplatelet therapy strategies to optimise the balance between ischaemic and bleeding risks.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants, investigators, and trial teams for their contributions to the TICO and T-PASS trials.

Funding

This study was supported by the Cardiovascular Research Center (Seoul, Republic of Korea) and ENCORE Seoul. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation; in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.