Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

A 78-year-old male presented with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. The Heart Team decided to perform a transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) with a 24.5 mm balloon-expandable Myval Octacor prosthesis (Meril Life Sciences)1.

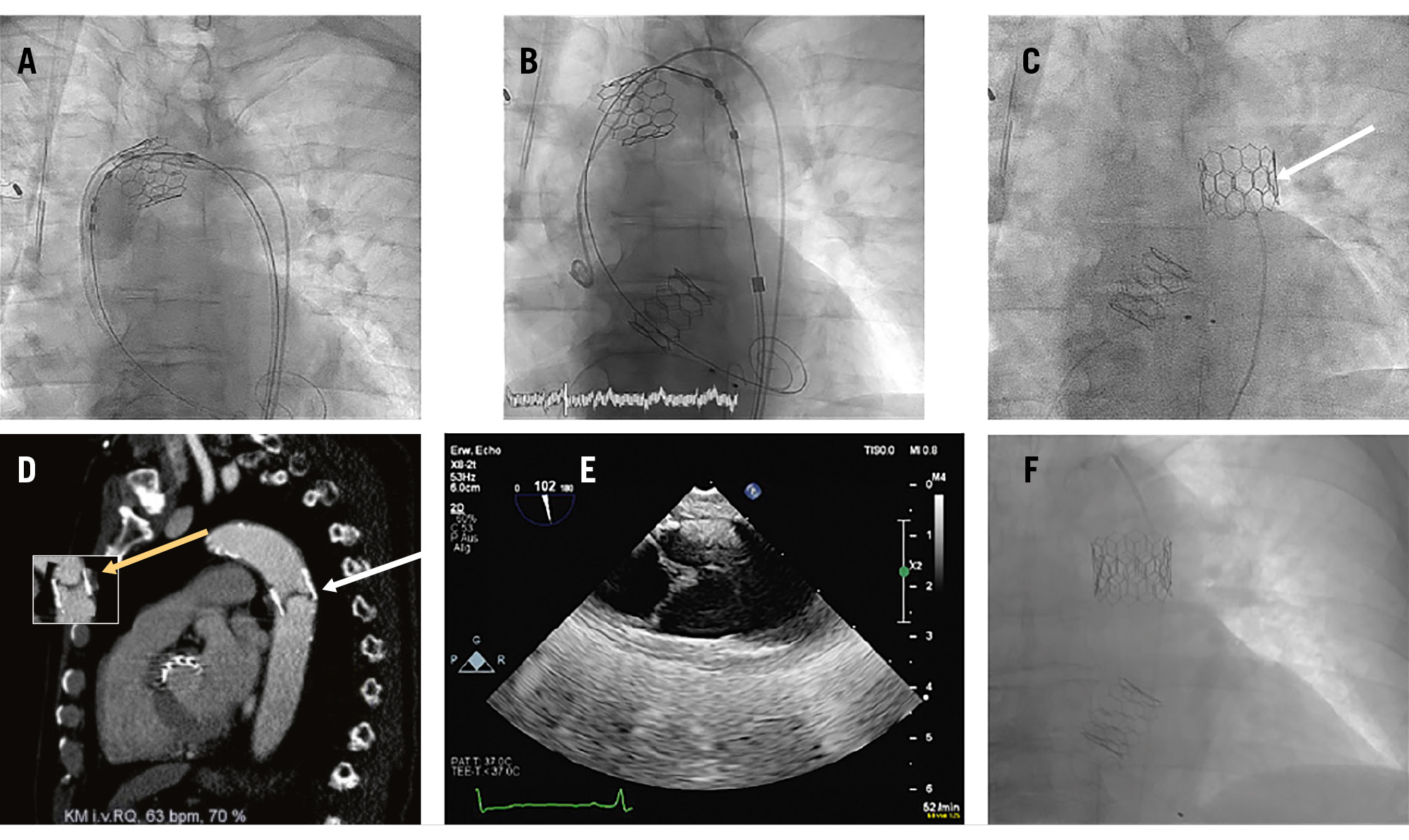

The TAVI procedure was performed in the early afternoon, between 12:40 pm and 1:25 pm. The patient was on permanent treatment with aspirin 100 mg/od and received unfractionated heparin during the procedure, which was controlled by activated clotting time measurement. During the implantation, the valve dislodged into the ascending aorta. Retrieval with a balloon into the descending aorta was not successful (Figure 1A) and a second 24.5 mm balloon-expandable Myval Octacor prosthesis was successfully implanted (Figure 1B). After withdrawal of the guidewire, spontaneous migration of the first valve into the descending aorta was seen. Due to the stable position of the dislodged valve (Figure 1C), the procedure was terminated, and the patient was transferred to an intermediate care unit, without any suspicious clinical signs. Palpable femoral pulses were documented during the late afternoon, and the patient received standard thromboembolic protection by subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin.

The next morning, at about 9 am, the patient complained of progressive paraplegia. Neurologists were contacted, who examined the patient, and a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed at 10 am. No abnormal finding was reported by the radiologists, nor by the neurologists, and a spinal cord embolisation was suspected (Figure 1D).

Due to persisting paraplegia, the CT scan was re-examined by our team at 2 pm, and an inversion of the dislodged prothesis was suspected (Figure 1D), leading to reduced peripheral and spinal perfusion. This was confirmed by the now-missing femoral pulses and by a transoesophageal echocardiography (Figure 1E).

We decided to implant a further 26 mm balloon-expandable Myval Octacor prosthesis, as a valve-in-valve procedure, into the dislodged prothesis, in the proper orientation (Figure 1F). Directly after the procedure, at 4:30 pm, femoral pulses could be palpated, and the paraplegia resolved within a week.

Re-examination of the initial implantation procedure revealed that the perforated longitudinal stent frames, indicating the upper row of the prosthesis, were proximally located (Figure 1C), indicating a twisted position of the valve within the descending aorta. The documented palpable pulses a few hours after the initial intervention as well as the initially missing pain and clinical symptoms may have been due to a persistent flow around the twisted dislodged valve. A small persisting flow besides the valve could still be documented in the transoesophageal echocardiography the following day, when symptoms were present (colour-coded Doppler image of the persistent flow not shown). We hypothesised that the twisted valve only slowly turned into an almost occlusive position, due to persistent pressure on the closed valve leaflets.

Paraplegia after TAVI is an extremely rare complication2. We have not seen another such scenario in more than 3,500 TAVI cases at our institution. Paraplegia is not specifically mentioned in the Valve Academic Research Consortium 3 consensus paper3, only potentially summarised as a symptomatic hypoxic-ischaemic injury with non-focal (global) neurological signs or symptoms with diffuse brain, spinal cord, or retinal cell death confirmed by pathology or neuroimaging and attributable to hypotension or hypoxia (Neurologic Academic Research Consortium Type 1e). Another reason for paraplegia could be embolisation into spinal arteries. In the case of the rather short balloon-expandable valves, spontaneous twisting of the valve after withdrawal of the guidewire, as in our case, must be kept in mind as a potential risk.

Another potential treatment option could be the implantation of a bare metal stent into the twisted valve, to press the valve leaflets aside and so to restore antegrade blood flow. However, no such stent was available at our institution at this time. In order not to prolong ischaemia, we decided to commence the valve-in-valve procedure as soon as possible.

We propose the following recommendations on how to act in case of an embolised balloon-expandable valve (BEV):

1. Do not retract the guidewire before you are convinced that the valve is in a stable, fixed position. With the guidewire in place, the BEV cannot twist.

2. Call a senior physician/another experienced colleague to obtain as much support as possible.

3. Try to position the BEV at a place where the chance to create an ischaemia is as low as possible, preferentially in the descending thoracic aorta.

4. In case of spontaneous migration of a BEV after the guidewire has been withdrawn, carefully look at the valve, using angiography, for the possibility of a rotation. There are structures on the valve which indicate the orientation of the valve (twisted or non-twisted). This is true for both the Edwards Lifesciences as well as the Meril Life Sciences valves.

5. In case of uncertainty about the orientation, look for clinical signs of rotation, such as palpable pulses, and perform at least one second imaging study, either a CT scan or a transoesophageal echocardiography.

Figure 1. Sequelae of a dislodged balloon-expandable Myval Octacor aortic valve prosthesis. A) Unsuccessful retrieval attempt of the dislodged valve with a balloon into the descending aorta. B) Implantation of a second 24.5 mm balloon-expandable Myval Octacor prosthesis. C) Position of the spontaneously migrated valve in the descending aorta (white arrow: perforated longitudinal stent frames, indicating the upper row of the prosthesis, which suggest that the valve is in a twisted position). D) CT scan of the chest after beginning of symptoms, with inversion of the dislodged prothesis (white arrow: valve leaflets located at the lower distal end of the valve). The small picture shows how a “normal view” of a non-twisted prosthesis would look (yellow arrow: valve leaflets located at the upper proximal end of the valve). E) Confirmation of the twisted position of the dislodged valve by a transoesophageal echocardiography, showing the valve leaflets located at the lower distal end of the valve (on the left side; the right side is the cranial side of the picture). F) A further 26 mm Myval Octacor prosthesis implanted as a valve-in-valve, into the dislodged prothesis, in a proper orientation. CT: computed tomography

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.