Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: In 2020, the Danish national guidelines changed to recommend prasugrel over ticagrelor in patients with myocardial infarction (MI) treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), prior to the 2023 update to the European guidelines.

Aims: We aimed to assess whether the shift from routine use of ticagrelor to prasugrel was implemented on a national level and whether prasugrel was associated with lower rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and with similar bleeding rates compared to ticagrelor.

Methods: This register-based cohort study identified MI patients treated with PCI from 2019 to 2022 using Danish nationwide registries. Patients without contraindications were included if they were alive and redeemed a prasugrel or ticagrelor prescription within 7 days from discharge.

Results: In total, 10,984 patients redeemed prasugrel (38.0%) or ticagrelor (62.0%). In 2019, >99% of patients were treated with ticagrelor. By 2022, 89% of patients were treated with prasugrel. Prasugrel-treated patients were younger, more often male, had ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) more frequently, and had fewer cardiovascular comorbidities than ticagrelor-treated patients. P2Y12 inhibitor adherence was high, and 4.3% of patients switched from prasugrel and 18.8% from ticagrelor. Prasugrel was associated with reduced 1-year rates of MACE (adjusted hazard ratio [adjHR] 0.67, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.47-0.95) and MI (adjHR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.44-0.96) compared with ticagrelor, without differences in bleeding after adjustment. These findings were replicated in a propensity score-matched population, in patients aged ≥75 years, and in non-STEMI patients.

Conclusions: A shift from ticagrelor to prasugrel occurred between 2019 and 2022 among real-world MI patients post-PCI. Prasugrel was associated with reduced rates of MACE and MI and with similar bleeding rates compared with ticagrelor, supporting current guideline recommendations.

In late 2019, the Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR-REACT 5) trial reported the results of a head-to-head comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients, 80% of whom were treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1. Contrary to the study’s hypothesis, prasugrel reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with ticagrelor, primarily driven by a lower incidence of myocardial infarction (MI), without a significant difference in the bleeding rate between the two drugs. The trial faced criticism for its open-label design, lower-than-expected event rates, and disparities in drug discontinuation rates, and many high-income countries continue to favour ticagrelor over prasugrel234. Nevertheless, current guidelines recommend prasugrel over ticagrelor in patients without contraindications5. Since 2020, the Danish Society of Cardiology has adopted this strategy in its national guidelines for ACS patients treated with PCI, as a direct consequence of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial6. It is unclear whether the transition from ticagrelor to prasugrel has been fully implemented on a national level and whether prasugrel use has led to fewer cardiovascular events and similar bleeding rates compared with ticagrelor, as real-world patients may differ from those in randomised trials. This study aimed to evaluate the shift from the routine use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with ticagrelor to prasugrel and to assess the associated cardiovascular and bleeding rates for prasugrel versus ticagrelor in all-comer MI patients treated with PCI.

Methods

Study design and data sources

In this nationwide register-based cohort study, data were retrieved from the following Danish registries: the Danish National Patient Registry, the Danish National Prescription Registry, and the Civil Registration System789. The Danish National Patient Registry contains information on all hospitalisations in Denmark, including admission and discharge dates, as well as diagnosis and operation codes classified according to the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) and the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP), respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The Danish National Prescription Registry provides details on redeemed prescriptions from every Danish pharmacy. The specific redeemed drugs were identified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) system codes, along with information on drug strength, quantity, and dispensing dates (Supplementary Table 2). The Civil Registration System includes data on sex, date of birth, emigration, and death. Every Danish resident receives a unique and permanent civil registration number at birth or immigration, allowing for individual-level linkage across these registries.

Study population

The study period spanned from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2022. All Danish citizens were included if they had an MI diagnosis and a PCI procedure code during a hospital stay lasting ≤30 days, a duration chosen to avoid outliers (Supplementary Table 1). For patients with multiple of these hospitalisations during the study period, only the first incident was considered. Comorbidities were identified based on diagnosis codes recorded any time before the index MI date. Patients with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack were excluded, as prasugrel is contraindicated in these individuals. Information on redeemed prescriptions 1 year prior to the index MI was also collected, including any antithrombotic drug, at least 2 antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, and antidiabetic drugs (Supplementary Table 2)10. Patients were stratified based on redeemed prasugrel or ticagrelor prescriptions within 7 days from discharge. It was assumed that acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 75 mg daily was used concomitantly as part of the DAPT regimen5. ASA prescriptions post-MI were not assessed, as many patients were already treated with ASA at the time of their index MI or could have obtained it over the counter, potentially leading to an underestimation of the actual use. Adherence to ticagrelor and prasugrel was assessed by calculating the total number of redeemed tablets in the first year after MI to determine the proportion of days covered11. The number of patients who switched from their initial potent P2Y12 inhibitor to another was also reported.

Outcomes

Follow-up began on day 8 after discharge and continued for 1 year after the MI (until 31 December 2023). Outcomes were defined based on diagnosis codes ascertained by the treating physician at the time of hospitalisation, and information on death came from the continuously updated civil registration system. The primary outcomes included MACE and bleeding leading to hospitalisation. MACE was a composite of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI (>28 days after the index MI, as defined by the Fourth Universal Definition of MI)12, and stroke. Bleeding leading to hospitalisation included cerebral, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urogenital bleedings, and bleeding-related anaemia. The secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, and stroke. Patients were followed until the occurrence of the first outcome of interest, the date of emigration, or death (for the outcomes excluding death), or 1 year after index MI, whichever occurred first.

Statistics

Ticagrelor was used as the reference throughout. Descriptive data are presented as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. The chi-squared test was applied to assess differences between categorical variables, or Fisher’s exact test was used when appropriate, and the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied for continuous variables. One-year incidence rates (IRs) per 100 person-years were calculated for all outcomes. For MACE, survival curves were plotted using the 1−Kaplan-Meier estimator, and differences between treatment groups were assessed using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence curves for bleeding leading to hospitalisation were constructed with the Aalen-Johansen estimator, accounting for death as competing risk, and Gray’s test was applied to calculate differences between treatment groups. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the rates of the outcomes according to the treatment groups, presented as adjusted hazard ratios (adjHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A significant interaction was found between treatment group and categorical age (<65, 65-74, and ≥75 years), but not for sex, type of MI (ST-segment elevation MI [STEMI], non-STEMI, or unspecified MI), or prior PCI. Therefore, the multivariable models were stratified by categorical age and adjusted for sex, type of MI, hypertension and/or use of at least 2 antihypertensive drugs, hypercholesterolaemia and/or statin use, diabetes and/or use of antidiabetic drugs, peripheral artery disease, prior PCI, prior bleeding, and calendar year. A propensity score-matched model was performed as a sensitivity analysis to account for baseline differences between prasugrel- and ticagrelor-treated patients. Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate the propensity scores including the same variables as in the multivariable analyses. Each prasugrel-treated patient was matched with one ticagrelor-treated patient on their propensity score (allowing a difference of ±0.05), categorical age, and calendar year to ensure a balance of these key variables between the groups. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were also applied to subgroups of elderly patients aged ≥75 years, STEMI, and non-STEMI patients. STEMI and non-STEMI patients were considered due to possible relevant differences in the underlying pathophysiology. The proportional hazards assumption was fulfilled in all models. A 2-sided p-value≤0.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests. SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), R, version 2022.07.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing)13, and BioRender were used14.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required for registry-based studies in Denmark. It was not possible to identify individual persons because the civil registration number was encrypted. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Results

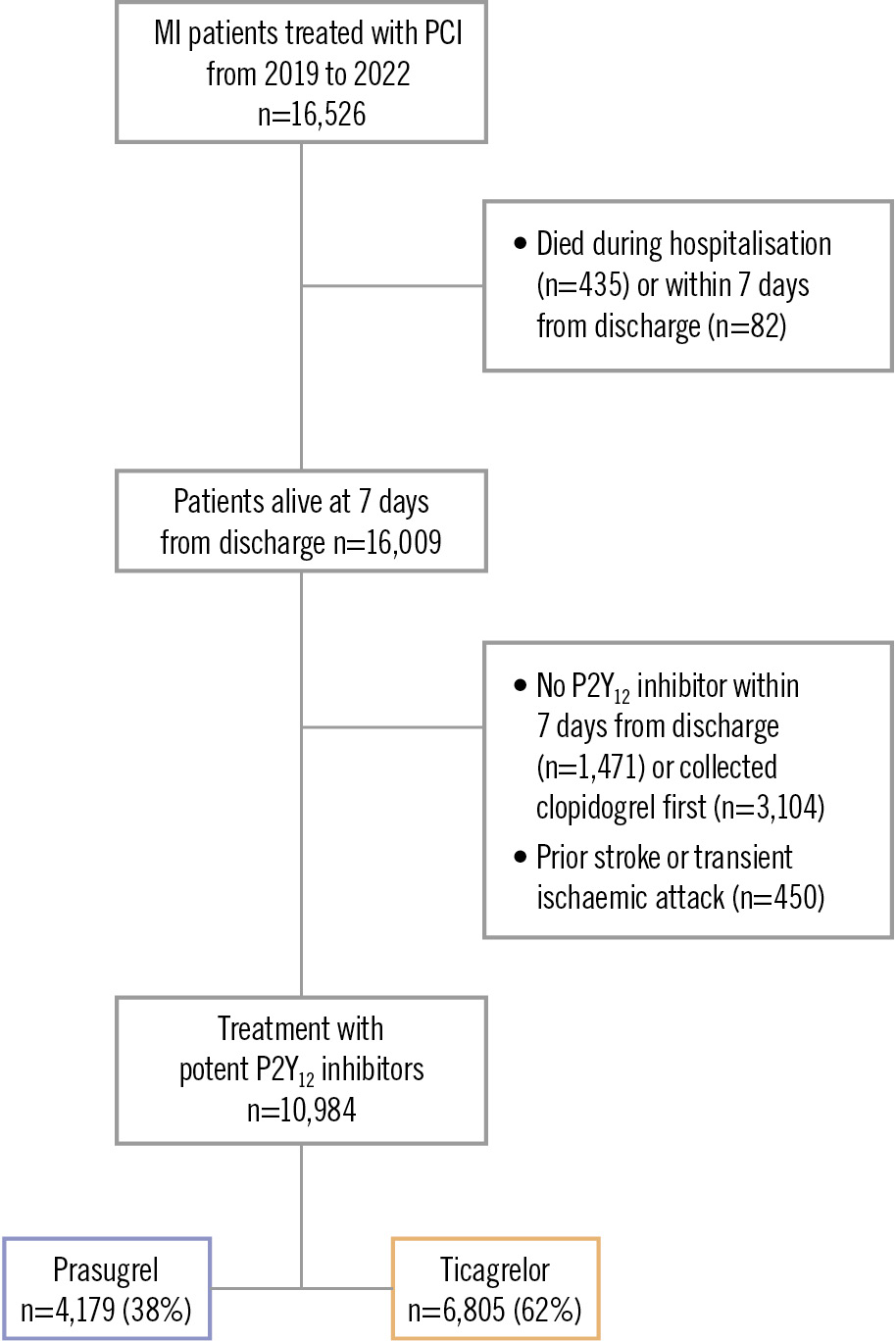

A total of 16,526 patients hospitalised with MI and treated with PCI were identified from 2019 to 2022 (Figure 1). Patients were excluded if, within 7 days from discharge, they died (3.1%), did not collect a P2Y12 inhibitor (9.2%), or collected clopidogrel first (21.4%), as were patients with prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack (3.9%). The final population comprised 10,984 patients, of whom 4,179 (38.0%) patients were treated with prasugrel and 6,805 (62.0%) with ticagrelor.

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient inclusion. MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Implementation of prasugrel

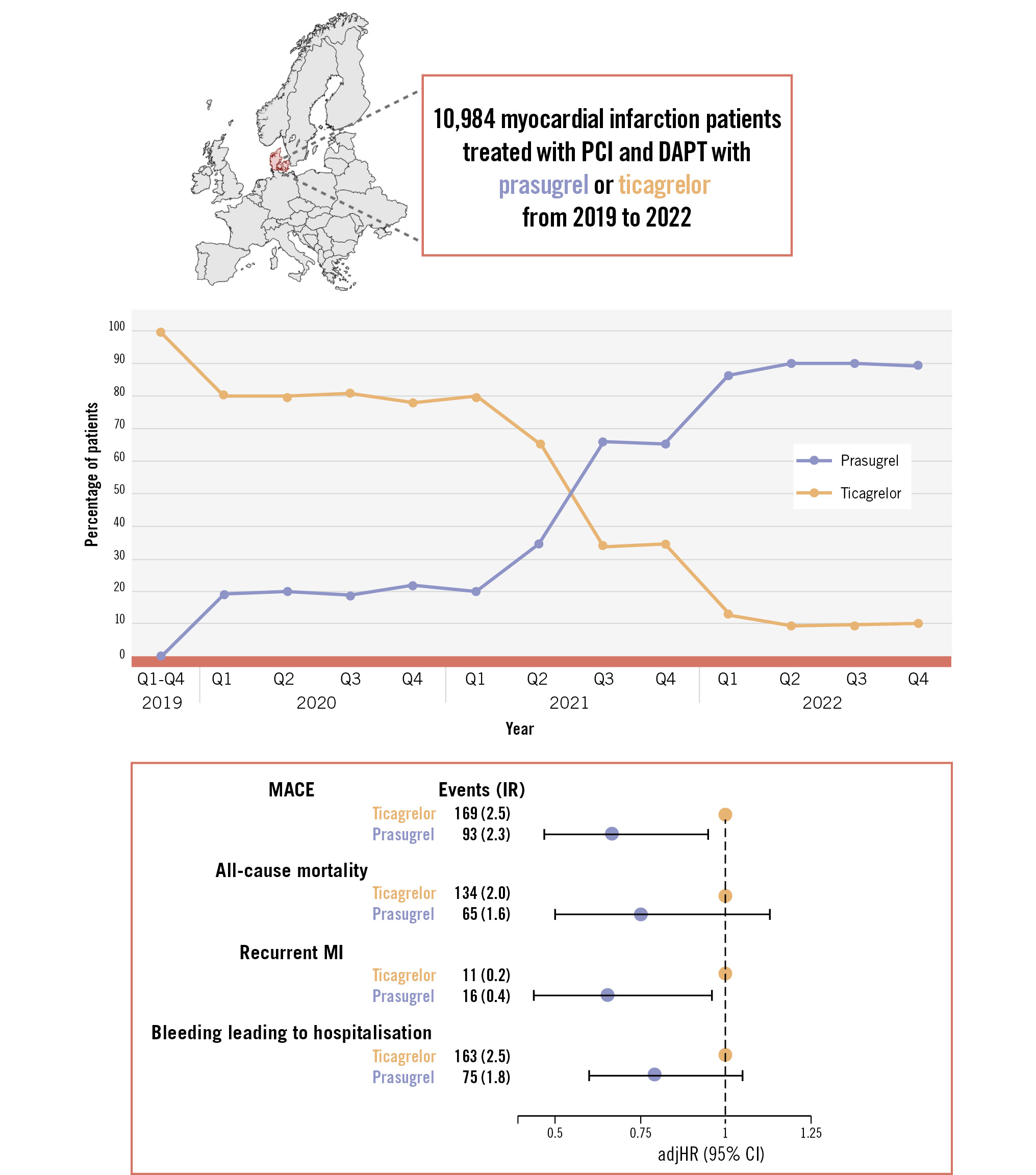

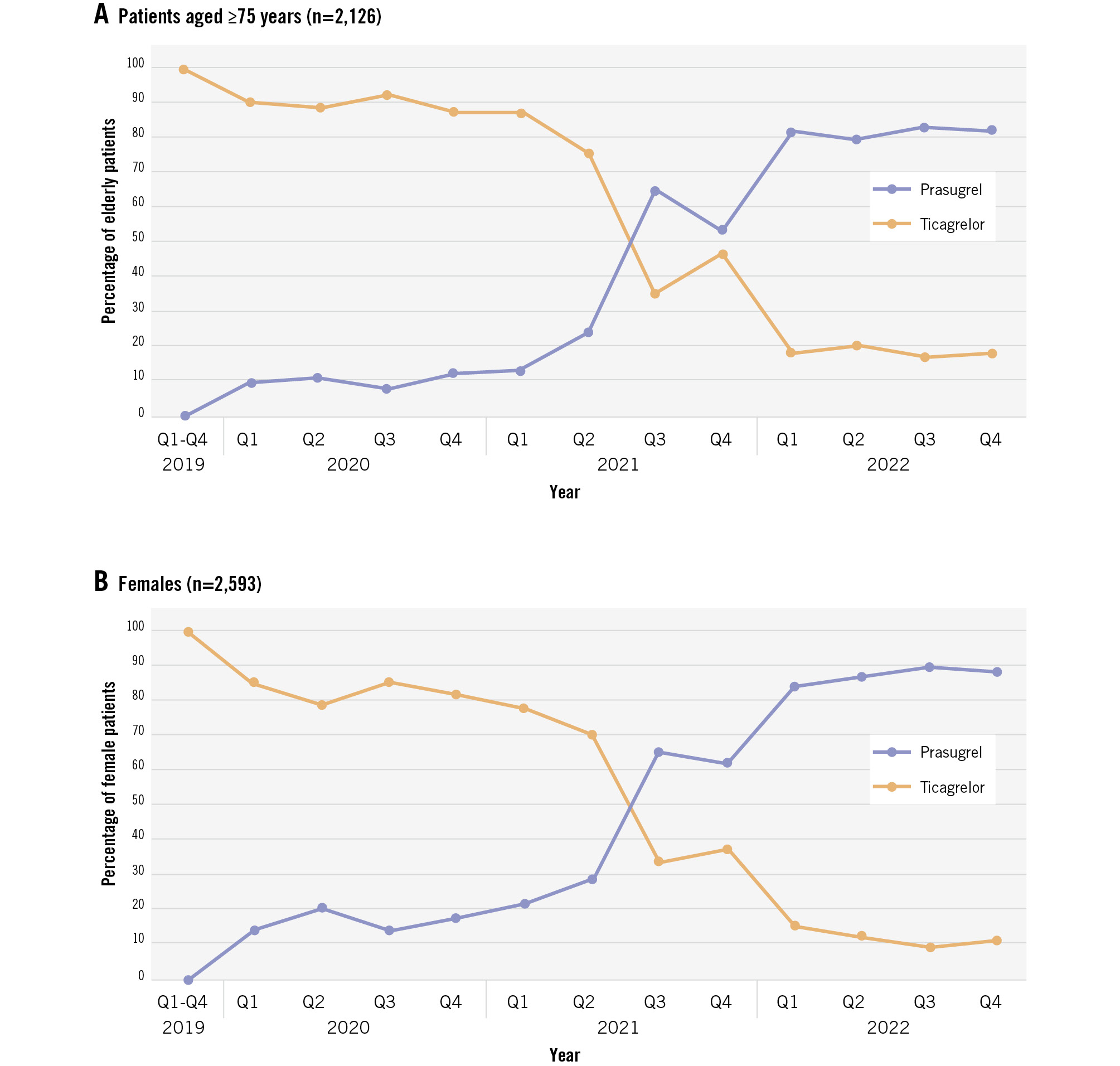

In 2019, more than 99% of MI patients treated with PCI received ticagrelor (Central illustration). The use of prasugrel began to increase in early 2020, surpassing ticagrelor use by the third quarter of 2021. By 2022, 89% of patients were treated with prasugrel. In the subgroup comprising 2,126 patients aged ≥75 years, similar trends were observed; however, approximately 20% of these patients continued to be treated with ticagrelor in 2022 (Figure 2A). Among the 2,593 female patients, the shift to routine prasugrel use resembled that of the total population (Figure 2B).

Central illustration. Shifting from the routine use of ticagrelor to prasugrel in all patients with myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention and the associated 1-year outcomes. Created with BioRender.com. adjHR: adjusted hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; IR: incidence rate per 100 person-years; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; Q: quarter

Figure 2. Temporal trends in the use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors in patients with myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Temporal trends in potent P2Y12 inhibitor use in patients aged ≥75 years (A) and in females (B). Q: quarter

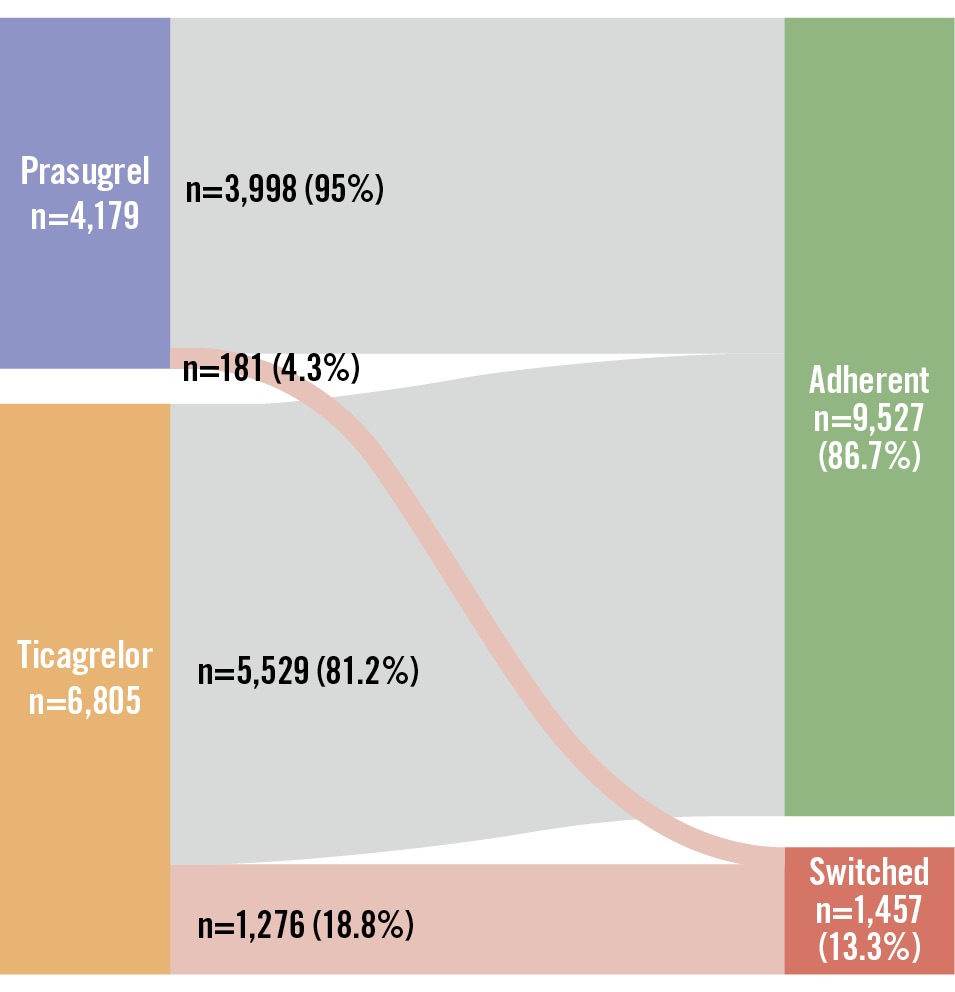

Descriptive characteristics

The median age of the population was 63 (IQR 55, 72) years, and 23.6% were female (Table 1). The median hospital stay was 3 (IQR 3, 4) days, and the median time to redeem the first potent P2Y12 inhibitor prescription was 1 (IQR 0, 2) day. The daily prasugrel dose was 10 mg in 3,425 (82.0%) patients and 5 mg in 754 (18.0%) patients; all ticagrelor-treated patients received 180 mg daily (data not shown). Prasugrel-treated patients were younger, more likely to be male or present with STEMI, and had fewer cardiovascular comorbidities than ticagrelor-treated patients. The proportion of days covered for the potent P2Y12 inhibitors in the first year after MI was high (median 0.96 [IQR 0.63, 1.00] from 2019 to 2022) but varied throughout the study period (Supplementary Table 3). Throughout the entire study period, 54.5% of the prasugrel-treated patients and 73.4% of the ticagrelor-treated patients had >80% of days covered. In the earlier period (2019 to 2021), these proportions were higher, with 87.0% of prasugrel-treated patients and 75.3% of ticagrelor-treated patients having >80% coverage. Additionally, 1,457 patients (13.3%) switched to another P2Y12 inhibitor, mostly clopidogrel (1,378 [94.6%]) within the first year post-MI (Supplementary Table 4). The number of switchers included 181 patients (4.3%) from the prasugrel group and 1,276 (18.8%) from the ticagrelor group (Figure 3).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Variables | Total (n=10,984) | Prasugrel (n=4,179) | Ticagrelor (n=6,805) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years | 63 [55, 72] | 62 [55, 71] | 64 [55, 73] | <0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| <65 years | 5,983 (54.5) | 2,413 (57.7) | 3,570 (52.5) | <0.001 |

| 65-74 years | 2,875 (26.2) | 1,094 (26.2) | 1,781 (26.2) | |

| ≥75 years | 2,126 (19.4) | 672 (16.1) | 1,454 (21.4) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 8,391 (76.4) | 3,251 (77.8) | 5,140 (75.5) | 0.007 |

| Female | 2,593 (23.6) | 928 (22.2) | 1,665 (24.5) | |

| Type of MI | ||||

| STEMI | 5,568 (50.7) | 2,688 (64.3) | 2,880 (42.3) | <0.001 |

| Non-STEMI | 4,113 (37.4) | 1,093 (26.2) | 3,020 (44.4) | |

| Unspecified MI | 1,303 (11.9) | 398 (9.5) | 905 (13.3) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 3,127 (28.5) | 1,085 (26.0) | 2,042 (30.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 2,097 (19.1) | 719 (17.2) | 1,378 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1,252 (11.4) | 436 (10.4) | 816 (12.0) | 0.013 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 221 (2.0) | 67 (1.6) | 154 (2.3) | 0.017 |

| Heart failure | 1,453 (13.2) | 552 (13.2) | 901 (13.2) | 0.96 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 220 (2.0) | 72 (1.7) | 148 (2.2) | 0.1 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 585 (5.3) | 203 (4.9) | 382 (5.6) | 0.09 |

| Renal disease | 447 (4.1) | 159 (3.8) | 288 (4.2) | 0.27 |

| Cancer | 1,294 (11.8) | 464 (11.1) | 830 (12.2) | 0.08 |

| Prior bleeding event | 1,124 (10.2) | 410 (9.8) | 714 (10.5) | 0.25 |

| Ulcer | 267 (2.4) | 97 (2.3) | 170 (2.5) | 0.59 |

| Prior PCI at any time | 1,339 (12.2) | 452 (10.8) | 887 (13) | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI 30 days before index MI | 28 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) | 18 (0.3) | 0.8 |

| Prior CABG at any time | 244 (2.2) | 67 (1.6) | 177 (2.6) | 0.001 |

| Drug use 1 year prior to MI | ||||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 2,047 (18.6) | 664 (15.9) | 1,383 (20.3) | <0.001 |

| Any P2Y12 inhibitor | 343 (3.1) | 109 (2.6) | 234 (3.4) | 0.015 |

| Anticoagulants | 58 (0.5) | 22 (0.5) | 36 (0.5) | 0.99 |

| At least 2 antihypertensive drugs | 3,021 (27.5) | 1,084 (25.9) | 1,937 (28.5) | 0.004 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 2,876 (26.2) | 1,017 (24.3) | 1,859 (27.3) | 0.001 |

| Antidiabetic drugs | 1,380 (12.6) | 507 (12.1) | 873 (2.8) | 0.28 |

| Index hospitalisation | ||||

| Median length of hospital stay, days | 3 [3, 4] | 3 [2, 4] | 3 [3, 4] | <0.001 |

| Potent P2Y12 inhibitors | ||||

| Median time to first P2Y12 inhibitor, days | 1 [0, 2] | 1 [0, 2] | 1 [0, 2] | <0.001 |

| Values are n (%) or median [IQR]. CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; IQR: interquartile range; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation MI | ||||

Figure 3. Patients switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor in the first year after myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. A Sankey plot of the number of patients who redeemed a prescription of prasugrel (blue box) or ticagrelor (orange box) within 7 days from discharge and either adhered (green box) to prasugrel (n=3,998, 95.7%) or ticagrelor (n=5,529, 81.2%) or switched (red box) from the initial P2Y12 inhibitor to another in the first year after myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention.

Outcomes

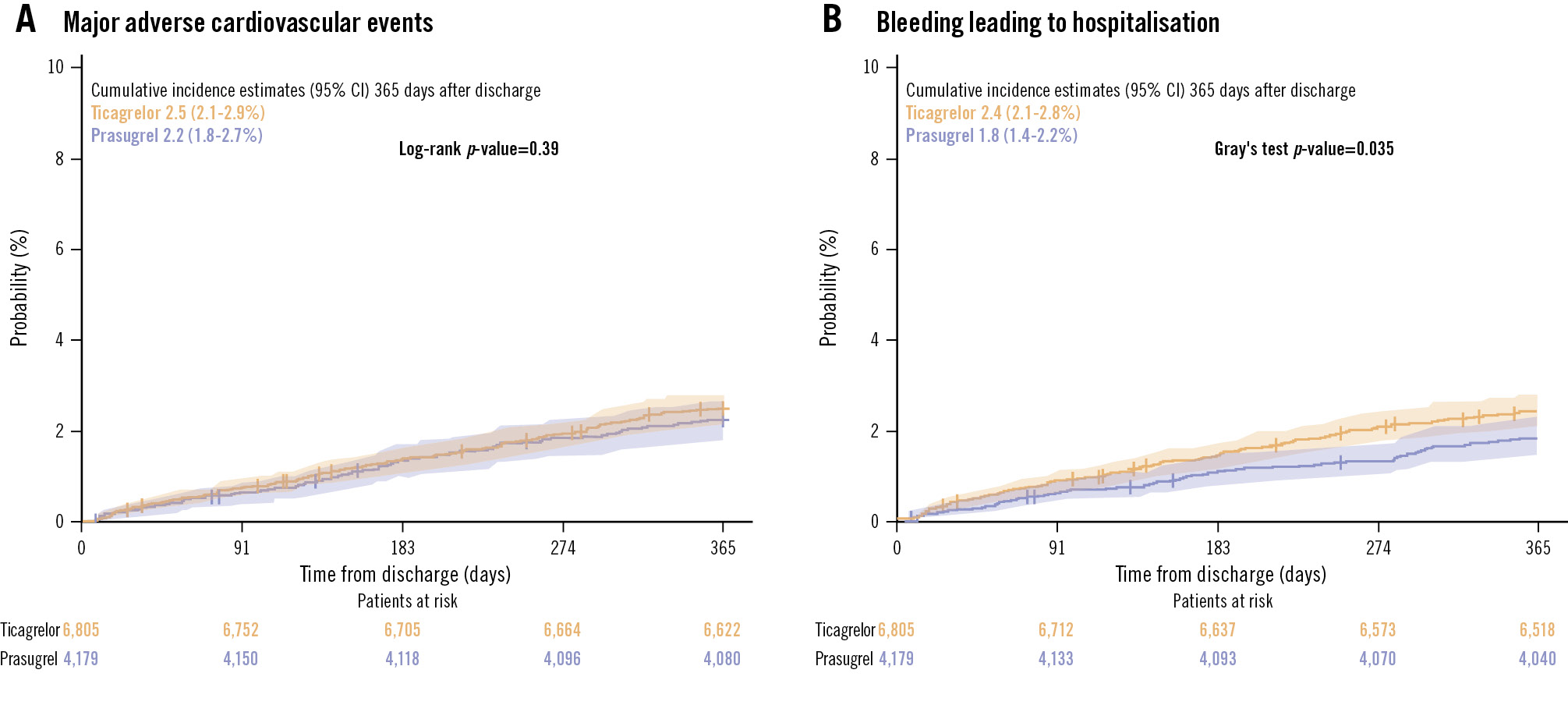

MACE occurred in 93 patients (IR 2.3) on prasugrel and in 169 patients (IR 2.5) on ticagrelor, and bleeding leading to hospitalisation occurred in 75 patients (IR 1.8) on prasugrel and in 163 patients (IR 2.5) on ticagrelor (Table 2). There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in the 1−Kaplan-Meier curve for MACE, but the cumulative incidence of bleeding leading to hospitalisation was significantly lower in prasugrel-treated patients than in ticagrelor-treated patients (Figure 4A, Figure 4B). Prasugrel treatment was associated with significantly reduced rates of MACE (adjHR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.47-0.95) and recurrent MI (adjHR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.44-0.96) compared with ticagrelor, without a significant difference in bleeding leading to hospitalisation (Table 2, Central illustration).

Table 2. Incidence rates of 1-year outcomes and adjusted hazard ratios for prasugrel versus ticagrelor.

| Outcomes* | All patients# (n=10,984) | Propensity score-matched models§ (n=3,934) | Patients aged ≥75 years¤ (n=2,126) | STEMI patients& (n=5,568) | Non-STEMI patients& (n=4,113) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events (IR) | adjHR(95% CI) | No. of events | adjHR(95% CI) | No. of events | adjHR(95% CI) | No. of events | adjHR(95% CI) | No. of events | adjHR(95% CI) | ||

| Prasugrel | Ticagrelor | ||||||||||

| MACE | 93 (2.3) | 169 (2.5) | 0.67(0.47-0.95) | 91 | 0.61(0.40-0.93) | 121 | 0.41(0.24-0.70) | 125 | 0.84(0.50-1.43) | 106 | 0.46(0.25-0.84) |

| All-cause mortality | 65 (1.6) | 134 (2.0) | 0.75(0.50-1.13) | 69 | 0.68(0.42-1.10) | 95 | 0.54(0.29-1.02) | 97 | 0.85(0.47-1.53) | 77 | 0.61(0.29-1.28) |

| Recurrent MI | 16 (0.4) | 11 (0.2) | 0.65(0.44-0.96) | 11 | 0.58(0.37-0.93) | 11 | 0.41(0.23-0.75) | 14 | 0.76(0.43-1.34) | 12 | 0.47(0.24-0.92) |

| Stroke | 15 (0.4) | 28 (0.4) | 0.75(0.52-1.08) | 15 | 0.69(0.45-1.08) | 19 | 0.5(0.29-0.89) | 17 | 0.93(0.54-1.61) | 21 | 0.57(0.30-1.08) |

| Bleeding leading to hospitalisation | 75 (1.8) | 163 (2.5) | 0.79(0.60-1.05) | 60 | 0.78(0.56-1.08) | 97 | 0.59(0.38-0.93) | 111 | 0.81(0.55-1.19) | 98 | 0.61(0.37-1.01) |

| *Patients could have had more than one type of event. #Stratified by categorical age and adjusted for sex, type of MI, hypertension and/or antihypertensive drugs, hypercholesterolaemia and/or lipid-lowering drugs, diabetes and/or antidiabetic drugs, peripheral artery disease, prior PCI, prior bleeding, and calendar year. §Propensity scores were calculated according to age, sex, type of MI, hypertension and/or antihypertensive drugs, hypercholesterolaemia and/or lipid-lowering drugs, diabetes and/or antidiabetic drugs, peripheral artery disease, prior PCI, prior bleeding, and calendar year; then matched on the propensity score, categorical age, and calendar year in the stratified Cox model. C-statistic: 0.908. ¤Adjusted for sex, type of myocardial infarction, hypertension and/or antihypertensive drugs, hypercholesterolaemia and/or lipid-lowering drugs, diabetes and/or antidiabetic drugs, PAD, prior PCI, prior bleeding, and calendar year. &Adjusted for categorical age, sex, hypertension and/or antihypertensive drugs, hypercholesterolaemia and/or lipid-lowering drugs, diabetes and/or antidiabetic drugs, PAD, prior PCI, prior bleeding, and calendar year. adjHR: adjusted hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; IR: incidence rate; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; PAD: peripheral artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | |||||||||||

Figure 4. One-year cumulative incidence curves of the primary outcomes in all patients. A) Major adverse cardiovascular events. B) Bleeding leading to hospitalisation. CI: confidence interval

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

The propensity score-matched model included 1,941 patients treated with prasugrel (46.4% of all prasugrel-treated patients) matched to 1,941 patients treated with ticagrelor. Their baseline characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table 5. The 1−Kaplan-Meier estimates of MACE were 1.8% (1.2-2.4%) for prasugrel and 2.9% (2.1-3.6%) for ticagrelor (log-rank p-value=0.027), and the cumulative incidence of bleeding leading to hospitalisation was 2.0% (1.4-2.7%) for prasugrel and 2.3% (1.7-3.1%) for ticagrelor (Gray’s test p-value=0.44) (Supplementary Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 1B). Prasugrel was associated with lower rates of MACE (adjHR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.40-0.93) and recurrent MI (adjHR 0.58, 95% CI: 0.37-0.93), without a significant difference in bleeding leading to hospitalisation (Table 2). A total of 2,126 patients were aged ≥75 years, of whom 672 (31.6%) were treated with prasugrel and 1,454 (68.4%) with ticagrelor. The daily dose of prasugrel was 5 mg in 448 patients (66.7%) and 10 mg in 224 patients (33.3%; data not shown). The median age was 79 (IQR 77, 83) years, and 35.8% were female. The baseline characteristics of patients aged ≥75 years are detailed in Supplementary Table 6. The 1−Kaplan-Meier estimates of MACE and the cumulative incidence for bleeding leading to hospitalisation are illustrated in Supplementary Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 2B. Prasugrel was associated with lower rates of MACE (adjHR 0.41, 95% CI: 0.24-0.70), recurrent MI (adjHR 0.41, 95% CI: 0.23-0.75), stroke (adjHR 0.50, 95% CI: 0.29-0.89), and bleeding leading to hospitalisation (adjHR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.38-0.93) compared with ticagrelor treatment (Table 2). A total of 5,568 (50.7%) patients had STEMI, 4,113 (37.4%) patients had non-STEMI, and for 1,303 (11.9%) patients, the MI diagnosis was not specified. Baseline characteristics of STEMI and non-STEMI patients are provided in Supplementary Table 7. One-year cumulative incidence estimates of the primary outcomes are illustrated for patients with STEMI (Supplementary Figure 3A, Supplementary Figure 3B) and non-STEMI (Supplementary Figure 4A, Supplementary Figure 4B). For STEMI patients, there were no significant differences in the primary or secondary outcomes between the treatments. In non-STEMI patients, prasugrel was associated with a lower rate of MACE (adjHR 0.46, 95% CI: 0.25-0.84) and recurrent MI (adjHR 0.47, 95% CI: 0.24-0.92) compared with ticagrelor, without a significant difference in bleeding leading to hospitalisation (Table 2).

Discussion

This study evaluated the transition from a default DAPT strategy with ticagrelor to one with prasugrel (in combination with ASA) in all-comer MI patients treated with PCI and the associated differences in prognostic outcomes. Several key findings emerged. First, prasugrel gradually replaced ticagrelor between 2020 and 2021, though approximately 10% of all patients continued to receive ticagrelor in 2022. Second, event rates were low across all patients regardless of the P2Y12 inhibitor used. Third, prasugrel treatment was associated with a significant reduction in MACE and recurrent MI compared with ticagrelor, with no significant difference in bleeding leading to hospitalisation. These findings were consistent in a propensity score-matched model, in patients aged ≥75 years, and in non-STEMI patients but not in STEMI patients. In 2019, more than 99% of patients were treated with ticagrelor. By 2022, 89% of patients were treated with prasugrel, leaving 11% still receiving ticagrelor. It can be speculated that some hospitals may have hesitated to fully shift to routine use of prasugrel after what were considered surprising results of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial. Additionally, ticagrelor may have been initiated as pretreatment in some MI patients without ST-segment elevation, particularly if the waiting time for a diagnostic coronary angiography was long, whereas prasugrel should only be administered after the coronary anatomy is known. Considering the differences at baseline, prasugrel might have been preferred in younger and healthier individuals and ticagrelor in elderly patients with a higher comorbidity burden. This could explain why a larger proportion of the patients aged ≥75 years were treated with ticagrelor in 2022 (nearly 20%). Elderly patients often have more complex coronary artery disease and, consequently, undergo more complex PCI procedures. It is possible that PCI operators favoured full-dose ticagrelor over low-dose prasugrel (5 mg daily) in patients aged ≥75 years. Notably, however, one-third of elderly patients in this study were treated with a 10 mg dose of prasugrel rather than the recommended 5 mg daily. It can be speculated that higher ischaemic risk or missing knowledge were potential reasons for this observation. All event rates in this study were low considering that all-comer patients were included. In the ISAR-REACT 5 trial, MACE rates were 6.9% with prasugrel and 9.3% with ticagrelor compared with 2.3% and 2.5%, respectively, in this study. Similarly, major bleeding rates were 4.8% with prasugrel and 5.4% with ticagrelor in the ISAR-REACT 5 trial, while in the current study, bleeding leading to hospitalisation occurred in 1.8% on prasugrel and 2.5% on ticagrelor. The lower event rates in this study may be due to the fact that patients had to survive and redeem a prescription of a potent P2Y12 inhibitor within 7 days from discharge. Although the median hospital stay was only 3 (IQR 3, 4) days, some early events are not included. Additionally, events were defined based on diagnosis codes from hospitalisations. While this is unlikely to have significantly affected the reported rates of recurrent MI and stroke, it may have non-differentially affected the reported bleeding rates. This is because bleeding events are also managed by general practitioners or in outpatient clinics and therefore not included in the administrative registries. On the other hand, we studied patients from a more recent period than that of ISAR-REACT 5. One-year mortality rates in patients with STEMI treated with PCI have been reported to decrease gradually, likely due to faster diagnosis in the prehospital setting, improved PCI techniques, and more effective secondary prophylactic treatment15. In fact, the 10-year mortality rate for Danish STEMI patients treated with PCI who survive beyond 3 months is only 2% higher than that of a matched-background population16. Despite the low event rates in this study, prasugrel was associated with reduced rates of MACE and recurrent MI compared with ticagrelor, replicating the findings of the ISAR-REACT 5 trial in a real-world population. These findings were consistent in non-STEMI patients. One plausible explanation for the associated differences in MACE and recurrent MI rates in favour of prasugrel could be the higher discontinuation rates among ticagrelor-treated patients, possibly due to side effects such as dyspnoea. This may have led to earlier discontinuation of DAPT or a switch to the less potent P2Y12 inhibitor, clopidogrel. Supporting this, 18.8% of patients initially on ticagrelor switched to another P2Y12 inhibitor, mainly clopidogrel, in the first year after MI compared with only 4.3% of patients initially on prasugrel. A similar trend was observed in the ISAR-REACT 5 trial, where discontinuation rates after 1 year were 15.2% for patients initially treated with ticagrelor and 12.5% for those treated with prasugrel, with the majority switching to clopidogrel1. While our data do not provide specific reasons for switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor, one may consider possible explanations for the observed differences in our observational study and the ISAR-REACT 5 trial. In our cohort, patients treated with ticagrelor were slightly older with a higher comorbidity burden compared to those treated with prasugrel. This may have contributed to a higher incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation during follow-up and a subsequent need for oral anticoagulation, prompting a switch from ticagrelor to clopidogrel more frequently than from prasugrel. Furthermore, the timing of follow-up in our study may partly explain the much lower discontinuation rate for prasugrel compared with that observed in the ISAR-REACT 5 trial. Since follow-up began 1 week after discharge, early discontinuation due to bleeding side effects, which are more common shortly after DAPT initiation, may not have been captured in our study. In contrast, non-bleeding side effects, such as ticagrelor-associated dyspnoea, which often persist beyond the initial hospitalisation period, are more likely to have been reflected in our data. Additionally, the proportion of days covered was higher in prasugrel-treated patients than in ticagrelor-treated patients during the early study period (2019 to 2021). A randomised trial was initiated in Denmark in 2022 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05262803) testing a 3-6 month DAPT strategy, in which most patients were treated with prasugrel. This could explain why the proportion of days covered in the first year after MI was lower for prasugrel-treated patients than ticagrelor-treated patients over the entire study period (2019 to 2022).

Limitations

This study included a nationwide cohort of almost 11,000 MI patients treated with PCI from 2019 to 2022 with available follow-up for all patients. The quality of the Danish national administrative registries is well established with a reported mean positive predictive value of ≥88% for the MI diagnosis17. Nonetheless, some degree of misclassification of the study population and their outcomes is inevitable in registry-based studies. Although the positive predictive value for MI diagnoses is high, it was assessed prior to the widespread implementation of high-sensitivity troponin assays. However, these assays were routinely used during our study period and may have led to some misclassification of myocardial injury as myocardial infarction. Importantly, such misclassification would likely be non-differential between the P2Y12 inhibitor groups. Furthermore, in line with the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction12, we excluded MI diagnoses occurring within 28 days of the index event in our definition of the recurrent MI outcome to reduce the risk of misclassification related to procedural myocardial injury. Additionally, the registries do not contain information on clinical (such as body weight) or procedural characteristics. Consequently, potential differences in baseline characteristics could not be accounted for in the adjusted models. Since patients were allocated to prasugrel or ticagrelor at the discretion of the treating physician, there is risk of confounding by indication. Moreover, temporal changes in other aspects of the patient’s treatment could potentially introduce confounding, although the relatively short 4-year study period reduces this risk. However, a randomised controlled trial comparing prasugrel and ticagrelor has already been conducted1, and the current study aimed to extend the findings of that trial to a real-world population. Nevertheless, there remains a need for a randomised cluster trial to compare the impact of a shift from a ticagrelor- to a prasugrel-based DAPT strategy in a real-world population. This is currently being investigated in the SWITCH SWEDEHEART study18. Another limitation of our study includes the assessment of adherence based on redeemed prescriptions rather than actual pill intake, which may lead to an overestimation of adherence.

Conclusions

Implementation of prasugrel as the preferred P2Y12 inhibitor for MI patients treated with PCI was achieved in Denmark by 2022. Prasugrel was associated with reduced rates of MACE and recurrent MI compared with ticagrelor treatment, with no difference in bleeding leading to hospitalisation. These findings support the current guidelines, which recommend prasugrel over ticagrelor for DAPT in patients without contraindications.

Impact on daily practice

In Denmark, a national shift from the routine use of ticagrelor to prasugrel in myocardial infarction (MI) patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention occurred between 2019 and 2022. Prasugrel was associated with reduced rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and MI, with no differences in bleeding compared with ticagrelor treatment. Higher discontinuation rates with ticagrelor may explain these findings. These real-world data further strengthen current guideline recommendations favouring prasugrel, which offers advantages such as once-daily administration and lower cost compared with ticagrelor.

Funding

This work was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant number 0071947) and Gangstedfonden (grant number R625-A41879), providing funding for M.R. Jacobsen’s PhD studentship. The funding sources were not involved in the study design, or the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Conflict of interest statement

R. Jabbari has received speaker honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb. E.L. Grove has received speaker honoraria or consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Lundbeck Pharma, and Organon; he is an investigator in clinical studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Idorsia, and Bayer; and has received unrestricted research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim. T. Geisler reports honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer/Chiesi, Novartis, and Pfizer; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ferrer, Edwards Lifesciences, Haemonetics, and Pfizer; and research grants from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Ferrer/Chiesi, Medtronic, and Edwards Lifesciences. T. Engstrøm has received speaker honoraria or consultancy fees from Bayer, Novo Nordisk, and Abbott; and he is an investigator in clinical studies sponsored by Novo Nordisk. R. Sørensen has received an institutional research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation; speaker honoraria from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AstraZeneca; and fees from Novo Nordisk for work on a data safety and monitoring board (not related to this work). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.