Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: A discrepancy exists between the European and American guideline recommendations for the routine use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in patients treated with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

Aims: This study aimed to determine the association between the co-prescription of PPIs and DAPT and the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding and ischaemic events in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods: A search was conducted using a nationwide Korean claims database to identify patients with AMI undergoing PCI with DAPT. Patients were matched using a large-scale propensity score (PS) algorithm according to the co-prescription of PPIs. The primary efficacy endpoint was major gastrointestinal bleeding requiring transfusion with hospitalisation within 1 year. The primary safety endpoint was major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous myocardial infarction, repeat revascularisation and ischaemic stroke within 1 year.

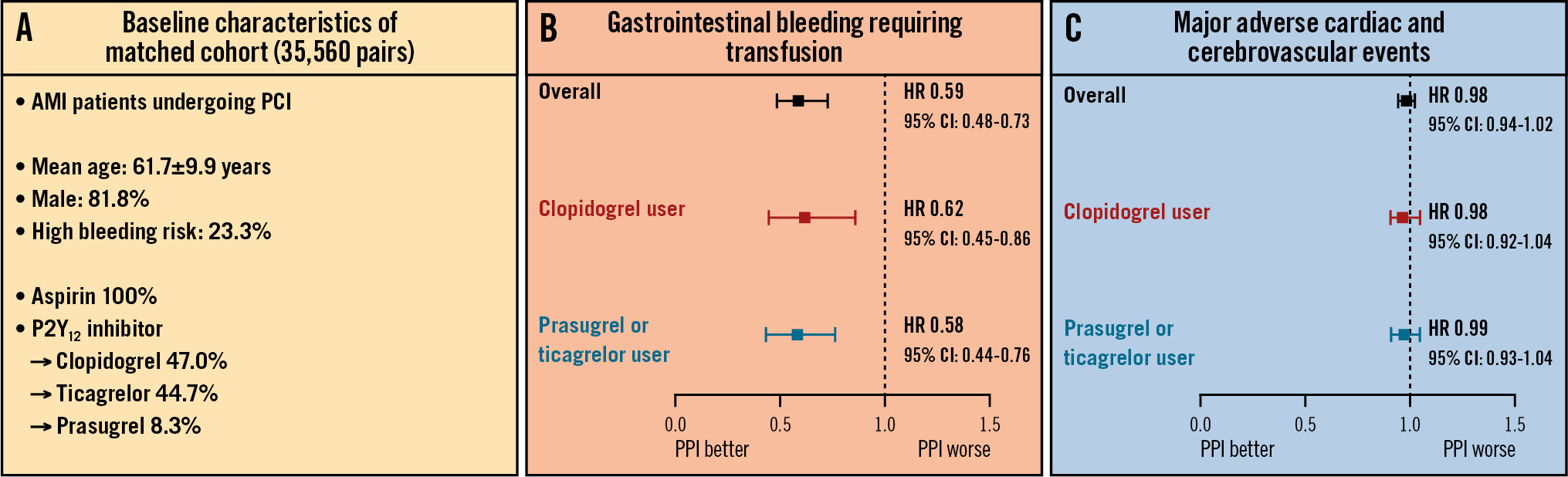

Results: Among the total population, 30.0% of patients (n=35,566) received PPIs with DAPT after PCI for AMI. After PS matching, 35,560 pairs were generated. Compared to patients without PPIs, those on PPIs were associated with a significantly lower 1-year risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding (0.7% vs 0.4%, hazard ratio [HR] 0.59, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.48-0.73). The 1-year risk of MACCE did not differ significantly between the groups with or without PPIs (13.4% vs 13.1%, HR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.94-1.02). The beneficial effects of PPIs on gastrointestinal bleeding, without increased risk of cardiovascular events, were observed consistently, regardless of P2Y12 inhibitor type, PPI type, or individual bleeding risk.

Conclusions: In real-world data from a large study of East Asian patients with AMI undergoing PCI and maintaining DAPT, PPI use significantly reduced the risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding without increasing ischaemic events, irrespective of bleeding risk or type of P2Y12 inhibitor. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06241833)

Across the spectrum of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), maintenance of 1-year dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is the standard care123. In particular, the development of potent P2Y12 inhibitors, including prasugrel or ticagrelor, has led to their preferred use over clopidogrel in patients with AMI to reduce further ischaemic events, but concerns about the risk of bleeding have increased456. In this regard, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend co-prescribing a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) with DAPT as a Class I recommendation to help reduce the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, which is the most common bleeding focus during the administration of DAPT78.

However, several studies have raised concerns that PPIs might reduce the antiplatelet activities of clopidogrel, possibly through the inhibition of cytochrome P450-2C19 (CYP2C19) isoenzyme, and thereby interfere with the conversion of clopidogrel into its active metabolite9101112. Although the Clopidogrel and the Optimization of Gastrointestinal Events trial (COGENT-1) indicated that the prophylactic use of PPIs in patients on DAPT, comprising aspirin plus clopidogrel, had gastrointestinal (GI)-protective effects and did not increase cardiovascular events, the trial was limited because it used a single PPI, omeprazole, and was stopped early13. Furthermore, there was limited evidence on the effects of PPIs on GI bleeding events in patients with AMI who continued potent P2Y12 inhibitor-based DAPT after PCI. Although substudies from the Study of PLATelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) and the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38 (TRITON-TIMI 38) identified the effect of PPIs in prasugrel or ticagrelor users, conflicting results regarding ischaemic events were obtained, and neither study showed a reduction in bleeding events1415. This is probably due to the failure to address the confounding factors of higher PPI use in patients at higher bleeding risk.

Therefore, we emulated a target trial16 to determine the effect of PPIs on GI bleeding and cardiovascular outcome in AMI patients maintained on DAPT after PCI and to confirm the interaction between the type of P2Y12 inhibitor and the use of PPIs, using a large nationwide cohort.

Methods

Data sources

This study was a nationwide retrospective analysis of the National Health Claims database established by the Korean National Health Insurance Service (K-NHIS). The K-NHIS database represents the entire population of Korea17, and all citizens are continuously enrolled unless they are ineligible because of emigration or death. This database contains all Korean healthcare information, including diagnoses, prescriptions, and surgical procedures.

Study participants

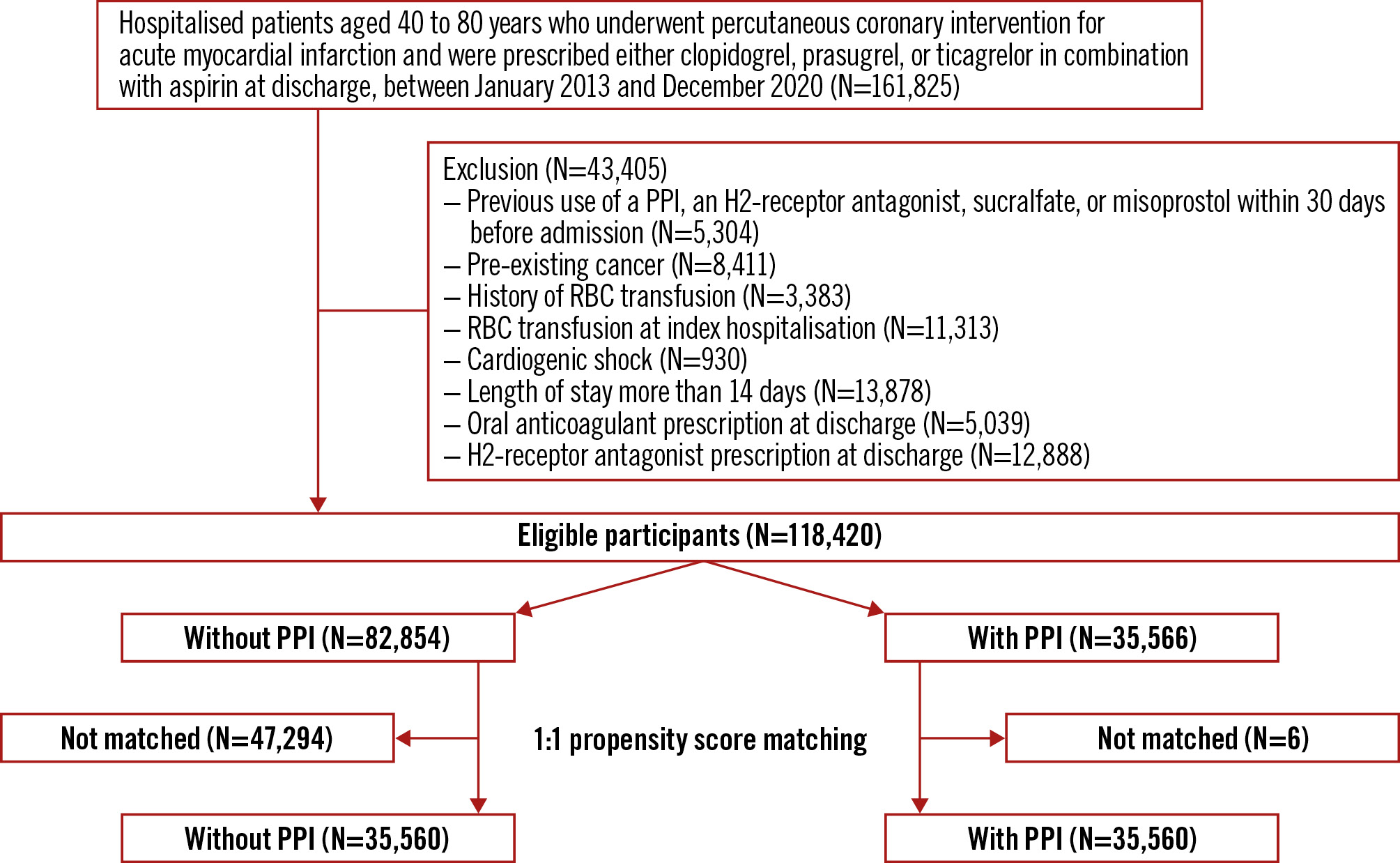

Among the 52 million Korean citizens included in the K-NHIS database, we identified 161,825 adult patients (aged 40-80 years) who underwent PCI for AMI and were treated with either clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor in combination with aspirin, between January 2013 and December 2020. In accordance with the eligibility criteria of the COGENT-1 trial, we excluded patients who had received a PPI, an H2-receptor antagonist, sucralfate or misoprostol within 30 days of admission (N=5,304); pre-existing active malignancy (N=8,411); a history of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions (N=3,383); or an RBC transfusion at index admission for AMI (N=11,313). Patients with severe conditions, including those who experienced cardiogenic shock (N=930) or had a length of stay exceeding 14 days (N=13,878), were also excluded. Additionally, patients who received other discharge medications that could affect bleeding, such as an oral anticoagulant (N=5,039) or H2-receptor antagonist (N=12,888), were excluded. Since study participants could have more than one exclusion criterion, the final sample size was 118,420 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study flowchart. PPI: proton pump inhibitor; RBC: red blood cell

Measurements

All procedures and prescriptions (mapped to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system) were coded using domestic codes. Diagnoses are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). As the K-NHIS routinely audits the claims, such data are considered reliable and are used in numerous peer-reviewed publications1819.

This study compared the outcomes between patients who received a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor as DAPT along with a PPI and those who received DAPT without a PPI. For the subgroup analysis of the P2Y12 inhibitor type, patients were classified into two groups based on their discharge medication: clopidogrel or prasugrel/ticagrelor. Patients who were prescribed both clopidogrel and prasugrel or ticagrelor as discharge medication were reclassified based on their prescribed medication at the next visit. Co-prescription of a PPI was defined as the presence of a prescription for dexlansoprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, or rabeprazole as a discharge medication, which is defined as a prescription of at least 2 days at discharge. In assessing compliance, we examined the percentage of patients who were both alive and consistently using a specific medication at a given point in time.

Baseline characteristics included age, sex, health-related behaviours, and comorbidities. Details of the data collection process and definitions of covariates are presented in Supplementary Appendix 1. Comorbidities, including history of myocardial infarction (MI), chronic heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, GI ulcer, anaemia, liver cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease with dialysis, stroke, and intracranial haemorrhage, were defined by diagnosis codes, prescription records, and inpatient and/or outpatient hospital visits within 1 year of admission (Supplementary Table 1). A high bleeding risk (HBR) was defined by the Academic Research Consortium (ARC)20.

Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was major GI bleeding, which was defined as hospitalisation, or an emergency room visit with diagnostic codes in the primary position and transfusion receipt. The definition demonstrated a positive predictive value of 92% for GI bleeding in a previous validation study21. Furthermore, we incorporated incidents of major or minor GI bleeding that necessitated hospitalisation, regardless of whether transfusion was required, as a secondary efficacy endpoint.

The primary safety endpoint was major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), which was defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous MI, repeat revascularisation, and ischaemic stroke. Vital status and cause of death were obtained from death certification data collected by Statistics Korea18. Cardiovascular death was defined by the presence of cardiovascular disease codes (I00-I78). Spontaneous MI (I21-I22) was defined by the presence of the diagnostic codes in the primary position during hospitalisation. In a validation study, the accuracy of diagnosis of MI in K-NHIS data was 93%22. Repeat revascularisation was defined by the presence of procedure codes for PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting after the index date. Ischaemic stroke was defined by the presence of the diagnostic codes for ischaemic stroke (I63-I64) in the primary position during hospitalisation with imaging procedures. The secondary safety endpoints were the individual components of the primary endpoint.

Statistical analysis

The propensity score (PS) was estimated in each emulated cohort to minimise the systematic differences in the baseline characteristics between the two groups. All covariates from claims data were included in the logistic regression model to estimate the probability of receiving treatment, conditional to their covariates. To minimise this bias, we implemented a 1:1 PS nearest-neighbour matching with a calliper width of 0.1 on the PS scale23. Differences in baseline covariates between the two groups were evaluated using an absolute standardised difference, with a value of>0.1 indicating a significant difference23. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using inverse probability treatment weighting with the PS.

The intention-to-treat approach was implemented, investigating the efficacy of the randomised assigned treatment, regardless of treatment adherence. To mimic this approach, patients were assigned to the “with PPI” or “without PPI” group, based on whether they were prescribed a PPI as their discharge medication, and matched for baseline covariates. Patients were followed up from the index date until outcome occurrence, death, the end of the study period (31 December 2021) or a prespecified time interval (1 year after PCI). Within the matched cohort, 1-year cumulative incidences of each endpoint were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and log-rank tests were used to evaluate differences between groups. We calculated hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the incidence of adverse events using the Cox regression model. We used robust standard errors to calculate the CI, given the matching data. We examined the proportional hazards assumption using plots of the log-log survival function and Schoenfeld residuals. Furthermore, we conducted subgroup analyses by age, sex, diabetes mellitus, type of P2Y12 inhibitor, history of GI ulcer and the presence of HBR20. Considering the low compliance of PPI in real-world data, a per-protocol analysis was also performed, which included only those patients who did not change group during the 1-year observation period.

All analyses were conducted using the SAS Enterprise Guide (version 7.1 [SAS Institute]) and R 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A 2-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Among 118,420 eligible participants, 30% (N=35,566) received a PPI along with DAPT as discharge medication. The mean age of the total population was 61.2 years, and 83.2% of patients were male. In a comparison of the entire cohort before emulating the COGENT-1 trial, eligible participants were more likely to be younger, to have a lower risk of bleeding, and to have received fewer prescribed discharge medications (Supplementary Table 2). Compared to AMI patients undergoing PCI on DAPT without PPI, those with PPIs were older, less likely to be male, and more likely to have a history of GI ulcer and ARC-HBR (Supplementary Table 3). After PS matching, 35,560 patients were assigned to the groups with and without PPI (Figure 1). There was no evidence of inequality in baseline characteristics, comorbidities, or medication history between the “with PPI” and “without PPI” groups (all standardised mean differences were <0.1) (Table 1). Compliance of PPIs, aspirin, and P2Y12 inhibitors at 1 year were 55.2%, 52.6%, and 50.0%, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of matched population.

| Overall (N=71,120) | Without PPI (N=35,560) | With PPI (N=35,560) | SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.68±9.90 | 61.62±9.87 | 61.75±9.94 | 0.013 |

| Sex, male | 58,191 (81.8) | 29,237 (82.2) | 28,954 (81.4) | 0.021 |

| Medical aid | 2,435 (3.4) | 1,148 (3.2) | 1,287 (3.6) | 0.021 |

| BMI, kg/m²# | 24.98±3.03 | 25.00±3.02 | 24.96±3.04 | 0.028 |

| Residential area, metropolitan | 43,020 (60.5) | 21,516 (60.5) | 21,504 (60.5) | 0.001 |

| Prior comorbidity | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 3,236 (4.6) | 1,496 (4.2) | 1,740 (4.9) | 0.033 |

| Chronic heart failure | 3,931 (5.5) | 1,840 (5.2) | 2,091 (5.9) | 0.031 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20,337 (28.6) | 10,011 (28.2) | 10,326 (29.0) | 0.020 |

| Hypertension | 22,589 (31.8) | 11,041 (31.0) | 11,548 (32.5) | 0.031 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 28,313 (39.8) | 13,975 (39.3) | 14,338 (40.3) | 0.020 |

| GI ulcer | 14,465 (20.3) | 7,079 (19.9) | 7,386 (20.8) | 0.021 |

| Anaemia | 1,749 (2.5) | 816 (2.3) | 933 (2.6) | 0.021 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 77 (0.1) | 34 (0.1) | 43 (0.1) | 0.008 |

| CKD with dialysis | 326 (0.5) | 152 (0.4) | 174 (0.5) | 0.009 |

| Stroke | 2,274 (3.2) | 1,072 (3.0) | 1,202 (3.4) | 0.021 |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 212 (0.3) | 101 (0.3) | 111 (0.3) | 0.005 |

| Use of steroids | 162 (0.2) | 82 (0.2) | 80 (0.2) | 0.001 |

| Use of NSAIDs | 111 (0.2) | 53 (0.1) | 58 (0.2) | 0.004 |

| ARC-HBR | 16,539 (23.3) | 7,998 (22.5) | 8,541 (24.0) | 0.036 |

| Heavy alcohol drinker* | 577 (1.5) | 293 (1.5) | 284 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker§ | 21,582 (42.9) | 10,711 (42.9) | 10,871 (42.9) | <0.001 |

| Admission from emergency room | 56,892 (80.0) | 28,612 (80.5) | 28,280 (79.5) | 0.023 |

| Medications at discharge | ||||

| Aspirin | 71,120 (100) | 35,560 (100) | 35,560 (100) | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 33,392 (47.0) | 16,617 (46.7) | 16,775 (47.2) | 0.009 |

| Prasugrel | 5,935 (8.3) | 3,104 (8.7) | 2,831 (8.0) | 0.028 |

| Ticagrelor | 31,793 (44.7) | 15,839 (44.6) | 15,954 (44.8) | 0.007 |

| Beta blocker | 55,755 (78.4) | 27,984 (78.7) | 27,771 (78.1) | 0.015 |

| ACEi | 27,730 (39.0) | 13,972 (39.3) | 13,758 (38.7) | 0.012 |

| ARB | 23,302 (32.8) | 11,553 (32.5) | 11,749 (33.0) | 0.012 |

| Statins | 68,976 (97.0) | 34,564 (97.2) | 34,412 (96.8) | 0.025 |

| Values are presented as n (%) or mean±SD. #For N=50,239; *for N=38,897; §for N=50,255. ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; ARC: Academic Research Consortium; BMI: body mass index; CKD: chronic kidney disease; GI: gastrointestinal; HBR: high bleeding risk; IQR: interquartile range; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||

Efficacy endpoints

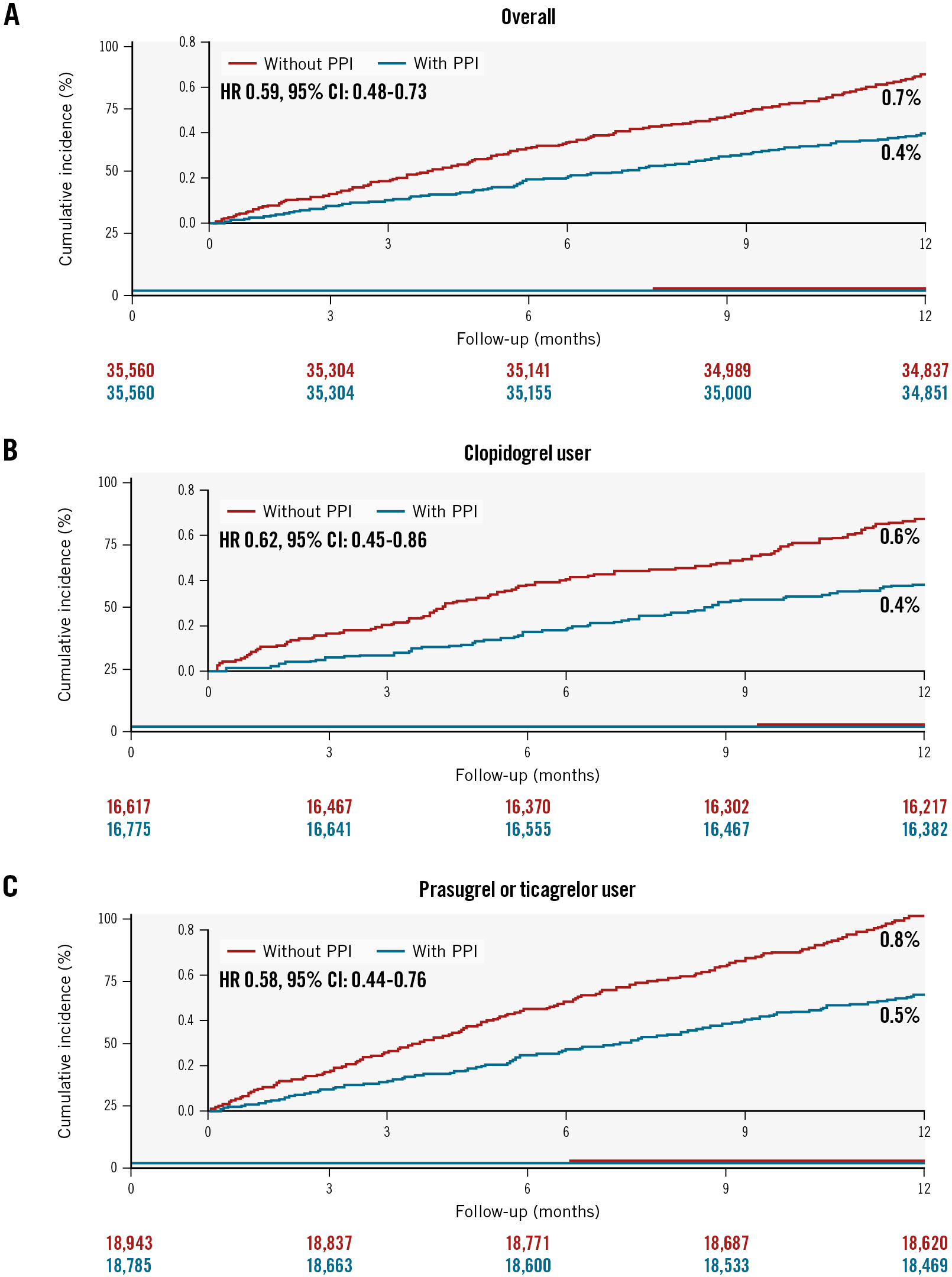

At 1 year, the group with PPIs had a significantly lower incidence of major GI bleeding requiring transfusion compared to the group without PPIs (0.7% vs 0.4%, HR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.48-0.73) (Table 2, Figure 2A). In the patients who were prescribed aspirin with clopidogrel (HR 0.62, 95% CI: 0.45-0.86) (Figure 2B) and in those prescribed aspirin with prasugrel or ticagrelor (HR 0.58, 95% CI: 0.44-0.76) (Figure 2C), PPI use was significantly associated with a lower risk of major GI bleeding requiring transfusion (Table 2). In subgroup analysis, the efficacy of PPIs was consistently observed in all subgroups, including the type of P2Y12 inhibitor (p for interaction=0.75), presence of HBR (p for interaction=0.49), and history of GI ulcer (p for interaction=0.21) (Supplementary Figure 1A). Furthermore, the beneficial effects of PPIs for GI bleeding were consistent across all types of PPIs (Table 3). Among patients with high adherence to PPI therapy, the use of PPIs was associated with a much lower risk of major GI bleeding requiring transfusion compared to the group without PPI use (HR 0.20, 95% CI: 0.16-0.27). The incidence rate of major or minor GI bleeding with hospitalisation was also lower in the PPI group than in the group who did not receive PPIs (Table 2). The results were also consistent using inverse probability treatment weighting (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2. Comparison of 1-year efficacy and safety endpoints according to the use of PPIs.

| Without PPI No. of events |

With PPI (1-year cumulative %) |

Without (ref) vs with PPIHR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Efficacy endpoints | |||

| Major GI bleeding requiring transfusion | 236 (0.7) | 140 (0.4) | 0.59 (0.48-0.73)§ |

| Major or minor GI bleeding with hospitalisation | 336 (1.0) | 236 (0.7) | 0.70 (0.60-0.83)§ |

| Safety endpoints | |||

| MACCE* | 4,714 (13.4) | 4,619 (13.1) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) |

| Cardiovascular death | 268 (0.8) | 295 (0.8) | 1.10 (0.93-1.30) |

| Spontaneous myocardial infarction | 2,319 (6.6) | 2,345 (6.7) | 1.01 (0.96-1.07) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 345 (1.0) | 385 (1.1) | 1.12 (0.97-1.29) |

| Repeat revascularisation | 2,743 (7.8) | 2,600 (7.4) | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) |

| Clopidogrel user | |||

| Efficacy endpoints | |||

| Major GI bleeding requiring transfusion | 92 (0.6) | 57 (0.4) | 0.62 (0.45-0.86)§ |

| Major or minor GI bleeding with hospitalisation | 128 (0.8) | 102 (0.6) | 0.79 (0.61-1.02) |

| Safety endpoints | |||

| MACCE* | 2,332 (14.2) | 2,298 (13.8) | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) |

| Cardiovascular death | 178 (1.1) | 174 (1.1) | 0.97 (0.79-1.19) |

| Spontaneous myocardial infarction | 1,093 (6.7) | 1,117 (6.7) | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 195 (1.2) | 232 (1.4) | 1.18 (0.98-1.43) |

| Repeat revascularisation | 1,330 (8.1) | 1,303 (7.9) | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) |

| Prasugrel or ticagrelor user | |||

| Efficacy endpoints | |||

| Major GI bleeding requiring transfusion | 145 (0.8) | 83 (0.5) | 0.58 (0.44-0.76)§ |

| Major or minor GI bleeding with hospitalisation | 208 (1.1) | 134 (0.7) | 0.65 (0.52-0.81)§ |

| Safety endpoints | |||

| MACCE* | 2,382 (12.7) | 2,321 (12.5) | 0.99 (0.93-1.04) |

| Cardiovascular death | 90 (0.5) | 121 (0.7) | 1.36 (1.03-1.78) |

| Spontaneous myocardial infarction | 1,226 (6.6) | 1,228 (6.7) | 1.01 (0.94-1.10) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 150 (0.8) | 153 (0.8) | 1.03 (0.82-1.29) |

| Repeat revascularisation | 1,413 (7.6) | 1,297 (7.0) | 0.93 (0.86-1.00) |

| *MACCE was defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke and repeat revascularisation. §indicates statistical significance. CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; PPI: proton pump inhibitor | |||

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence of major GI bleeding requiring transfusion up to 1-year follow-up. Kaplan-Meier curves are shown to compare major GI bleeding requiring transfusion according to the use of PPIs in patients overall (A), in clopidogrel users (B), and in potent P2Y12 inhibitor users (C) with AMI undergoing PCI on DAPT. AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; GI: gastrointestinal; HR: hazard ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI: proton pump inhibitor

Table 3. Comparison of 1-year efficacy and safety endpoints according to the type of PPI.

| Without PPI (N=35,560) | Dexlansoprazole (N=4,740) | Esomeprazole (N=8,516) | Lansoprazole (N=11,268) | Omeprazole (N=450) | Pantoprazole (N=4,382) | Rabeprazole (N=6,204) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Primary efficacy endpoint(major GI bleeding requiring transfusion) | Reference | 0.29 (0.15-0.56) | 0.62 (0.44-0.88) | 0.55 (0.39-0.76) | 0.34 (0.05-2.38) | 0.72 (0.46-1.13) | 0.80 (0.56-1.15) |

| Primary safety endpoint (MACCE*) | Reference | 0.86 (0.78-0.94) | 1.05 (0.98-1.11) | 0.93 (0.87-0.98) | 0.90 (0.68-1.18) | 0.96 (0.88-1.05) | 1.11 (1.04-1.20) |

| Clopidogrel user | |||||||

| Primary efficacy endpoint(major GI bleeding requiring transfusion) | Reference | 0.31 (0.15-0.63) | 0.53 (0.33-0.85) | 0.61 (0.40-0.92) | NA | 0.62 (0.28-1.41) | 0.86 (0.55-1.33) |

| Primary safety endpoint (MACCE*) | Reference | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | 1.06 (0.97-1.15) | 0.96 (0.88-1.05) | 1.16 (0.76-1.78) | 0.94 (0.79-1.11) | 1.05 (0.95-1.16) |

| Prasugrel or ticagrelor user | |||||||

| Primary efficacy endpoint(major GI bleeding requiring transfusion) | Reference | 0.13 (0.02-0.95) | 0.76 (0.44-1.32) | 0.48 (0.28-0.83) | 0.62 (0.09-4.42) | 0.88 (0.51-1.51) | 0.68 (0.35-1.30) |

| Primary safety endpoint (MACCE*) | Reference | 0.90 (0.77-1.05) | 1.04 (0.95-1.15) | 0.88 (0.81-0.96) | 0.74 (0.52-1.07) | 0.93 (0.84-1.04) | 1.21 (1.09-1.33) |

| *MACCE was defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, or repeat revascularisation. GI: gastrointestinal; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; NA: not applicable; PPI: proton pump inhibitor | |||||||

Safety endpoints

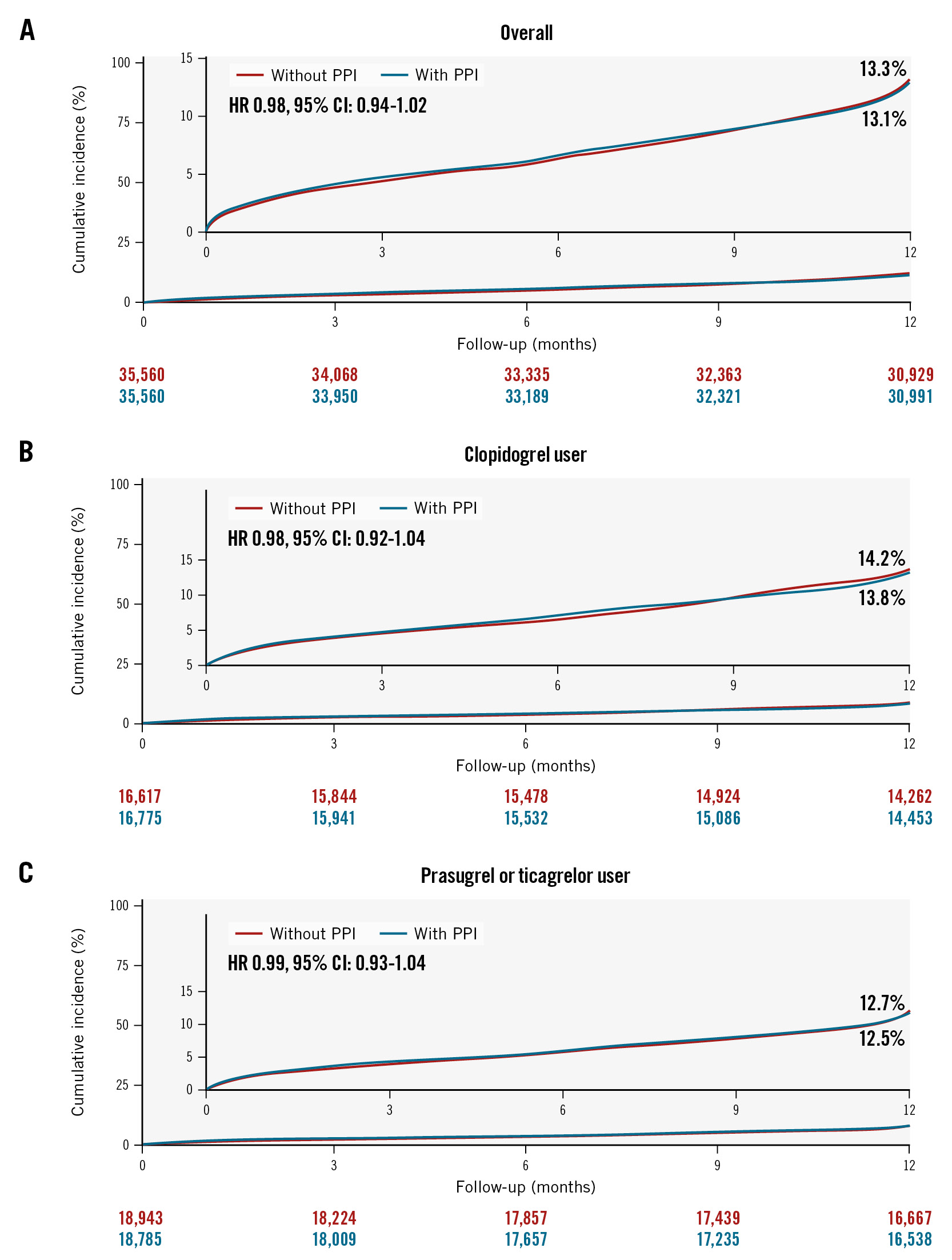

At the 1-year follow-up, MACCE occurred in 4,714 patients in the group who did not receive PPIs and in 4,619 patients in the PPI group, with corresponding incidence rates of 13.4% and 13.1%, respectively (HR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.94-1.02) (Table 2, Figure 3A). There was no difference in the risk of MACCE between the two groups for patients prescribed aspirin with clopidogrel (HR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.92-1.04) (Figure 3B) and those prescribed aspirin with prasugrel or ticagrelor (HR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.93-1.04) (Figure 3C). In subgroup analysis, the PPI group showed no significant difference in the risk of MACCE compared to the group without PPIs. This was consistent across all subgroups, including the P2Y12 inhibitor type (p for interaction=0.83) (Supplementary Figure 1B). Furthermore, no harmful effects were observed across all types of PPIs (Table 3). For the secondary endpoints, there were no significant differences in the incidence rates of cardiovascular death, spontaneous MI, repeat revascularisation, or ischaemic stroke between the patients who received PPIs and those who did not, regardless of the type of P2Y12 inhibitor (Table 2).

Figure 3. Cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events up to 1-year follow-up. Kaplan-Meier curves are shown to compare major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous MI, repeat revascularisation, and ischaemic stroke) according to the use of PPIs in patients overall (A), in clopidogrel users (B), and in potent P2Y12 inhibitor users (C) with AMI undergoing PCI on DAPT. AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; GI: gastrointestinal; HR: hazard ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI: proton pump inhibitor

Discussion

This emulation of a randomised trial using a nationwide cohort investigated the effects of PPI co-prescription on major GI bleeding and cardiovascular outcomes in AMI patients using DAPT after PCI, stratified by the type of P2Y12 inhibitor (Central illustration). The main findings were as follows. First, even after exclusion of the high GI bleeding risk population, in whom there is a mandatory need for short-term or long-term use of a PPI, the concomitant use of PPIs with DAPT was associated with a significantly lower risk of major GI bleeding events for 1 year in patients with AMI undergoing PCI. The beneficial effects of PPIs on major GI bleeding were observed consistently, irrespective of the type of P2Y12 inhibitor or PPI. Second, co-prescription of any PPI type did not increase the risk for cardiovascular ischaemic events in either the population with aspirin plus clopidogrel or the population with aspirin plus prasugrel or ticagrelor. Third, the results of reducing GI bleeding without increasing cardiovascular events in patients who were prescribed a PPI during DAPT maintenance were consistent in both the populations with and without HBR.

As awareness and understanding of the prognostic importance of bleeding has grown, the design of drug-eluting stents and advances in other medical treatments have improved. For instance, antiplatelet strategies after PCI for AMI patients, such as high-intensity statins, are becoming less intensive in order to minimise the risk of bleeding24. Another strategy used to reduce GI bleeding, which is the most common serious complication of antithrombotic therapy, is the concomitant administration of PPIs. However, in real-world practice, the prescription rates of PPI prophylaxis are still low even in patients with DAPT maintenance who are at a higher risk of GI bleeding25. This could be attributed to the recommendation discrepancy between the ESC and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines726. In the ESC guideline, routine use of PPIs for all patients on DAPT is recommended as a Class I indication. However, the ACC/AHA guideline stipulates that only patients at high risk of bleeding should receive PPIs, and routine PPI use is discouraged (Class III) in patients treated with DAPT26. This discrepancy might be caused by a difference in the interpretation of previous conflicting results from the randomised trial and registry data involving the potential interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel. The COGENT-1 trial, which is a randomised trial for evaluating the effects of PPIs among patients receiving aspirin and clopidogrel, demonstrated that the prophylactic use of omeprazole reduced the rate of upper GI bleeding without an increased risk of cardiovascular events13. Similarly, a Danish nationwide registry showed that the use of PPIs was associated with a lower risk of upper GI bleeding events in AMI patients taking DAPT25. However, that study did not present an analysis of ischaemic events to identify PPI-clopidogrel interactions, even though clopidogrel was used in the majority of the cohort.

Therefore, this study was conducted to confirm the effects of PPIs on GI bleeding by controlling baseline differences through PS matching within populations that mimic trials (predominantly low bleeding risk populations). We used patient-level claims data from the Republic of Korea to emulate the randomised trial. One of the major strengths of this study was that we focused on clinically meaningful events, i.e., major GI bleeding events requiring transfusion with admission, in a large sample size. In this study, we found that major GI bleeding events were reduced significantly when a PPI was administered concurrently with DAPT in both AMI populations treated with aspirin plus clopidogrel and those with aspirin plus potent P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel or ticagrelor). Notably, we first demonstrated the GI-protective effects of PPIs in patients with AMI on potent P2Y12 inhibitor-based DAPT maintenance, which is the most popular strategy for AMI patients in contemporary practice. Furthermore, we also found that the beneficial effects of PPIs on major GI bleeding were observed consistently, irrespective of the various types of PPI. Considering that the co-prescription of a PPI with DAPT showed benefits in terms of major GI bleeding events, regardless of the presence of HBR or GI ulcer history, our findings support the ESC guideline of recommending the routine use of a PPI in patients on DAPT.

Pharmacodynamic investigations have observed a reduction in the antiplatelet efficacy of clopidogrel when co-administered with PPIs, attributed to the competitive inhibition of CYP2C19, which plays a major role in activating clopidogrel27. Several observational studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated a relationship between PPIs and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing PCI28. In this regard, both the European Medicines Agency and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration released statements warning of a potential interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel and discouraging their combined use in the absence of a strong indication. However, the COGENT-1 trial reported that there was no significant increase in the risk of cardiovascular events with the concomitant use of clopidogrel and omeprazole13. Based on this result, the current guidelines recommend the use of PPIs, even in clopidogrel users, without warning, if indicated. However, the COGENT-1 trial was stopped before enrolling the planned 5,000 patients due to financial issues (actual enrolment of 3,873 patients), and the relatively short follow-up period (6 months) may have resulted in an insufficient sample size to identify the differences in ischaemic events according to the use of PPIs. In the current study, using an emulated randomised trial from a large real-world dataset (35,560 pairs of PS matching), we found that the concomitant use of PPIs did not increase ischaemic events in patients with AMI undergoing PCI on either potent P2Y12 inhibitor- or clopidogrel-based DAPT. Although a previous study showed that the clopidogrel-PPI interaction is known to be drug specific and not a class-specific effect depending on the degree of interference with CYP2C19 activity29, the current study found that there was no significant difference in terms of cardiovascular risk according to any type of PPI co-prescription in clopidogrel users. One of the major strengths of the current study is that it found an effect on ischaemic events when different types of PPIs were used in combination with DAPT after PCI. Considering that the current study population is exclusively East Asian, with a higher proportion of clopidogrel resistance than Western populations30, our results suggest that any type of PPI could be used safely in patients with AMI, even those receiving clopidogrel-based DAPT, irrespective of ethnicity.

Central illustration. Benefits of concomitant PPI use and DAPT in AMI patients undergoing PCI. The current study evaluated the association between the co-prescription of PPIs and DAPT with the occurrence of GI bleeding and ischaemic events in patients with AMI undergoing PCI. Using a large-scale PS-matching algorithm according to the co-prescription of PPIs from a nationwide South Korean claims database, 35,560 pairs of AMI patients undergoing PCI on DAPT were generated (A). The co-prescription of PPIs and DAPT showed beneficial effects with regard to reducing major GI bleeding (B) without an increased risk of cardiovascular events (C), regardless of the P2Y12 inhibitor type. These findings promote routine PPI use in AMI patients on DAPT treated with PCI. AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; GI: gastrointestinal; HR: hazard ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; PS: propensity score

Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, explicit target trial emulation alone cannot eliminate the bias that arises from lack of randomisation, even if the observational analysis correctly emulates all other components of the target trial. The relatively high rate of MACCE in the current study might be influenced by the selection of a high-risk population after the PS matching process and the exclusive enrolment of patients with AMI. Second, detailed information for platelet function tests, genotype, dosage of aspirin, angiographic findings, and PCI procedures were not available because of the nature of the claims dataset. Third, certain risk factors for GI bleeding, such as Helicobacter pylori infection, were unavailable. Fourth, the number of patients with HBR was relatively small after excluding those requiring the inevitable use of PPIs. Fifth, compliance with the use of PPIs was not optimal, which could have influenced the results. Sixth, although this study showed a statistically significant reduction in major GI bleeding risk with PPI use in patients on DAPT, the absolute risk reduction is relatively small, and it resulted in a high number needed to treat. However, given that PPIs are relatively inexpensive and pose no ischaemic risk trade-off, this result may not diminish the significance of these findings.

Conclusions

Even among patients with a predominantly low GI bleeding risk who required DAPT following PCI for AMI, co-prescription of PPIs showed a significantly lower risk of major GI bleeding requiring transfusion during 1 year. The beneficial effects of PPIs on GI bleeding were observed consistently, regardless of P2Y12 inhibitor type, PPI type, or individual bleeding risk. Furthermore, PPI use was not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in patients treated with either clopidogrel or potent P2Y12 inhibitors.

Impact on daily practice

In a retrospective nationwide cohort study that included 35,560 propensity score-matched pairs, the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) was associated with a lower risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding after 1 year. There was no significant difference in the risk of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous myocardial infarction, repeat revascularisation, and ischaemic stroke) between the use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with or without PPIs. The beneficial effects of PPIs on gastrointestinal bleeding, without an increased risk of cardiovascular events, were observed consistently, regardless of P2Y12 inhibitor type, PPI type, or individual bleeding risk. These findings promote routine PPI use in patients on DAPT.

Acknowledgements

A reproducible research statement and details on author contributions and ethical approval can be found in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the submitted work to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.