Abstract

BACKGROUND: A short dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) duration has been proposed for patients at high bleeding risk (HBR) undergoing drug-eluting coronary stent (DES) implantation. Whether this strategy is safe and effective after a non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) remains uncertain.

AIMS: We aimed to compare the impact of 1-month versus 3-month DAPT on clinical outcomes after DES implantation among HBR patients with or without NSTE-ACS.

METHODS: This is a prespecified analysis from the XIENCE Short DAPT programme involving three prospective, international, single-arm studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of 1-month (XIENCE 28 USA and Global) or 3-month (XIENCE 90) DAPT among HBR patients after implantation of a cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent. Ischaemic and bleeding outcomes associated with 1- versus 3-month DAPT were assessed according to clinical presentation using propensity score stratification.

RESULTS: Of 3,364 HBR patients (1,392 on 1-month DAPT and 1,972 on 3-month DAPT), 1,164 (34.6%) underwent DES implantation for NSTE-ACS. At 12 months, the risk of the primary endpoint of death or myocardial infarction was similar between 1- and 3-month DAPT in patients with (hazard ratio [HR] 1.09, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.71-1.65) and without NSTE-ACS (HR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.63-1.23; p-interaction=0.34). The key secondary endpoint of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) Type 2-5 bleeding was consistently reduced in both NSTE-ACS (HR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.37-0.88) and stable patients (HR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.61-1.15; p-interaction=0.15) with 1-month DAPT.

CONCLUSIONS: Among HBR patients undergoing implantation of an everolimus-eluting stent, 1-month, compared to 3-month DAPT, was associated with similar ischaemic risk and reduced bleeding at 1 year, irrespective of clinical presentation.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor is recommended for up to 12 months after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) to prevent recurrent ischaemic events12. However, DAPT is encumbered by a significant risk of bleeding complications, which are proportional to the duration of treatment and negatively affect patient morbidity and mortality345. Up to 40% of patients undergoing PCI present with clinical conditions associated with a high bleeding risk (HBR) that make prolonging the duration of DAPT unattractive678. Among those patients, a DAPT duration shorter than the standard 6-month course has been proposed to mitigate the bleeding risk without compromising the antithrombotic protection9, but evidence in support of this practice in an ACS setting is scarce1011121314.

The XIENCE Short DAPT clinical programme has previously demonstrated that among HBR patients undergoing PCI with cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stents for either an acute or chronic coronary syndrome, but without ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), DAPT for 1 or 3 months followed by aspirin monotherapy was non-inferior to a historical control of 6- or 12-month DAPT for ischaemic outcomes and superior in preventing bleeding151617. Moreover, in the overall study population, the 1-month regimen, compared with the 3-month, was associated with a similar ischaemic risk and further reduced bleeding events at 1 year17. With the present analysis, we aimed to compare the impact of 1-month versus 3-month DAPT on the clinical outcomes of HBR patients undergoing PCI according to clinical presentation (i.e., with or without non-ST-segment elevation ACS [NSTE-ACS]).

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

This is a prespecified substudy within the XIENCE Short DAPT programme, which consisted of three prospective, multicentre trials conducted at 101 sites in the USA (XIENCE 90; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03218787), 58 sites in the USA and Canada (XIENCE 28 USA; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03815175), and 52 sites in Europe and Asia (XIENCE 28 Global; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03355742) from July 2017 to February 2020. The study rationale, design, and principal results have been previously reported151617. In brief, this clinical programme explored two different DAPT durations in patients undergoing PCI with a fluoropolymer-based cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent (XIENCE [Abbott]). The XIENCE 28 and 90 studies were executed under near-identical protocols, except for the DAPT duration. It was prespecified that the USA and Global studies of XIENCE 28 were to be pooled together for data analysis. Abbott sponsored the studies. An independent data monitoring committee provided external oversight to ensure public safety. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent.

STUDY POPULATION

After successful PCI with the XIENCE stent, patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if at least one of the following HBR criteria was met: age ≥75 years, indication for chronic anticoagulant therapy, history of major bleeding within 12 months of the index procedure, history of ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, renal insufficiency (creatinine ≥2.0 mg/dL) or failure (maintenance dialysis), anaemia (haemoglobin <11 g/dL), and systemic conditions associated with an increased risk for bleeding, including haematological disorders such as thrombocytopaenia (platelet count <100,000/mm3) and coagulation disorders151617. All studies allowed treatment of up to 3 target lesions, with a maximum of 2 target lesions per epicardial vessel, and treatment of bifurcation lesions without 2-stent techniques during index PCI. Key exclusion criteria were presentation with STEMI, implantation of a drug-eluting stent other than a cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent in the previous 12 months, target lesions that were in-stent restenosis or chronic total occlusions, those requiring overlapping stents, located in the left main stem, arterial or venous graft, or lesions containing thrombus (for XIENCE 90 only). After index PCI, all patients received open-label aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor, preferably clopidogrel. Eligibility to discontinue DAPT was assessed at 1 month after index PCI in XIENCE 28 and at 3 months in XIENCE 90. Patients who had been adherent to treatment and free from myocardial infarction (MI), repeat coronary revascularisation, stroke, and stent thrombosis discontinued the P2Y12 inhibitor and continued aspirin until the end of the study. Follow-up was performed in person or via telephone at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after index PCI in XIENCE 28, and at 3, 6, and 12 months in XIENCE 90. Per the study protocol, eligibility to discontinue DAPT was assessed at different time points in the XIENCE 28 and 90 programmes. Patients from XIENCE 90 who were event free and adherent to treatment at 1 month were retrospectively selected to match the XIENCE 28 event-free population.

CLINICAL ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause death or MI between 1 and 12 months after index PCI. The key secondary endpoint was Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) Type 2 to 5 bleeding18. Other secondary endpoints included target lesion failure (a composite of cardiovascular death, target vessel MI, or target lesion revascularisation), the individual components of the composite endpoints, stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, and BARC Type 3 to 5 bleeding. All clinical events were adjudicated by an independent event committee.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The effects of 1- versus 3-month DAPT on ischaemic and bleeding outcomes were evaluated according to clinical presentation (NSTE-ACS vs chronic coronary syndrome [CCS]) at the time of PCI. The clinical and procedural characteristics of each group are summarised using means and standard deviations for continuous variables or counts and percentages for categorical ones. The Chi-square test and Student’s t-test were used to compare groups, as appropriate. The cumulative incidence rates for both the primary and secondary endpoints were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were generated using Cox proportional hazard models. Because the treatment arms were not randomised, adjusted risks for all endpoints were estimated using propensity score stratification into quintiles. Propensity scores were derived using a logistic regression model that included the treatment group as the outcome and the selected baseline demographic, clinical, and procedural covariates as the predictors1617. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation method was applied to handle missing data in the propensity score building with the Within approach19. The Rubin’s combination rule was used to integrate the final analysis with each of the 10 imputed datasets. Supplementary Figure 1 shows 10 different balance plots with standardised mean differences in baseline covariates before and after propensity score stratification. Heterogeneity of treatment effects by clinical presentation was examined with a subgroup by treatment interaction term.

As all patients in the trials were treated with single antiplatelet therapy (i.e., aspirin) after 3 months of PCI, landmark analyses at 3 months were performed to isolate the effects of actual treatment difference (1-3 months) between the two DAPT arms. In a secondary analysis, treatment effects were estimated across the spectrum of NSTE-ACS presentation, including non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina, with formal interaction testing to assess for effect modification. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding patients on oral anticoagulation from the comparison between 1- versus 3-month DAPT. A 2-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp).

Results

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

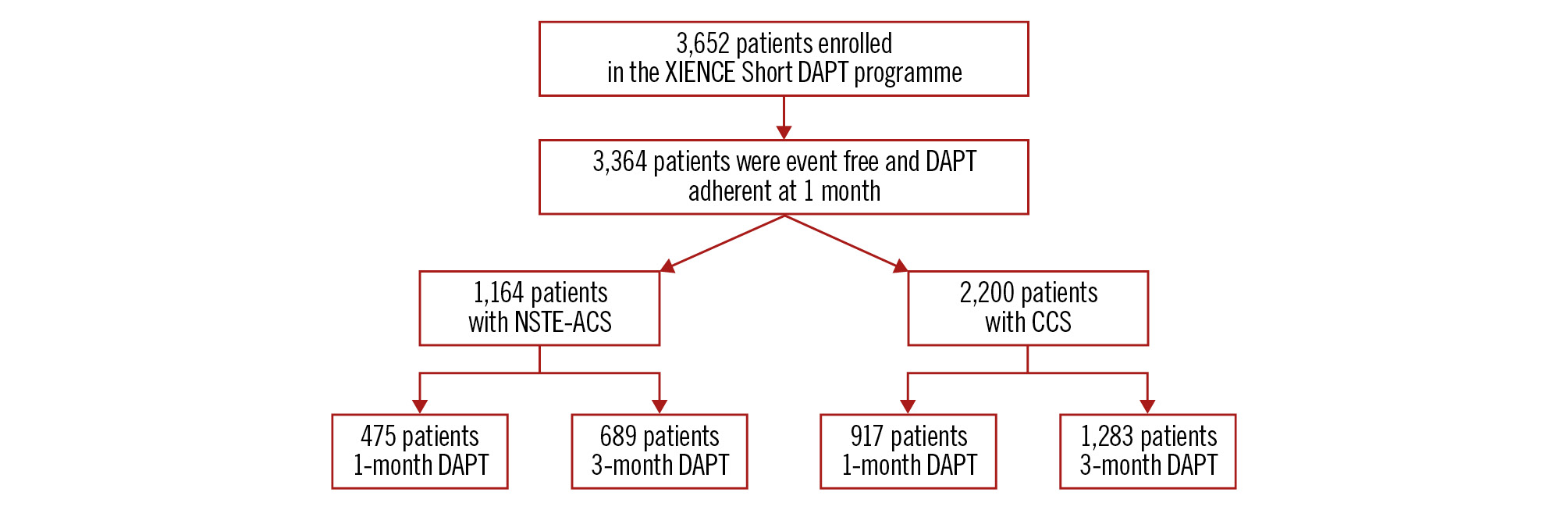

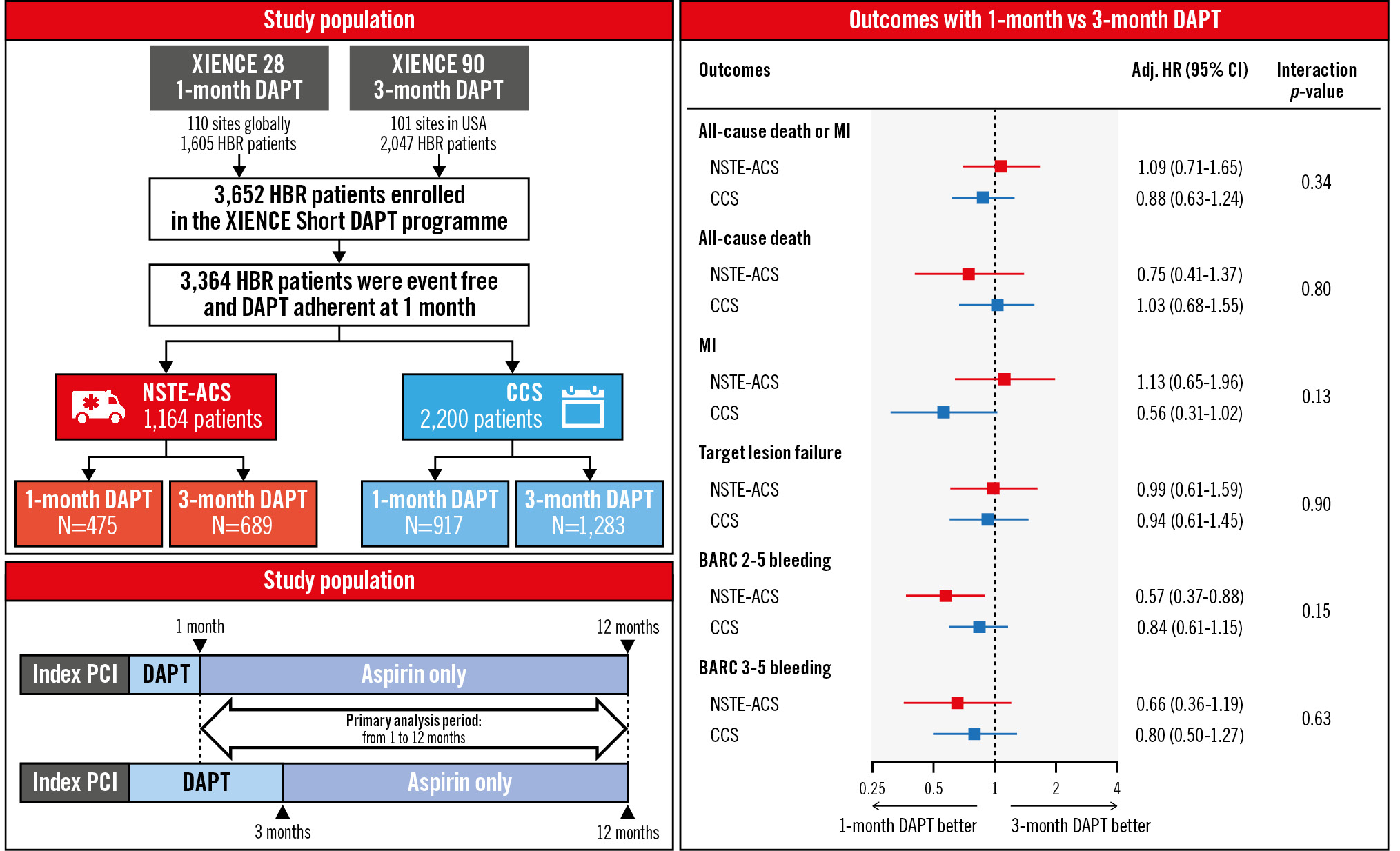

A total of 3,652 patients were enrolled in the XIENCE Short DAPT programme. Out of 3,364 eligible patients at 1 month (Figure 1), 1,164 (34.6%) patients had undergone PCI for NSTE-ACS, and 2,200 (65.4%) for CCS. Among NSTE-ACS patients, 475 received 1-month DAPT and 689 received 3-month DAPT; in the CCS group, 917 and 1,283 were treated with 1- and 3-month DAPT, respectively (Figure 1).

Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics by clinical presentation are reported in Supplementary Table 1. NSTE-ACS patients were more likely to be women, Asian or African American, to have a history of MI, anaemia, and higher Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) and Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimens in Stented Patients (PARIS) bleeding scores2021. Radial access, complex lesions, and ticagrelor use at discharge were more frequent among NSTE-ACS patients. Baseline characteristics according to treatment arm by clinical presentation are summarised in Table 1, while DAPT use at different time points up to 1 year is reported in Supplementary Figure 2.

Figure 1. Study population. CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| NSTE-ACS (N=1,164) | CCS (N=2,200) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-month DAPT N=475 (40.8) |

3-month DAPT N=689 (59.2) |

p-value | 1-month DAPT N=917 (41.7) |

3-month DAPT N=1,283 (58.3) |

p-value | |

| High bleeding risk criteria | ||||||

| Age ≥75 years | 308 (64.8) | 447 (64.9) | 0.990 | 641 (69.9) | 845 (65.9) | 0.046 |

| Chronic anticoagulant therapy | 201 (42.3) | 280 (40.6) | 0.568 | 416 (45.4) | 525 (40.9) | 0.036 |

| Anaemia | 90 (18.9) | 119 (17.3) | 0.464 | 111 (12.1) | 194 (15.1) | 0.045 |

| History of stroke | 54 (11.4) | 86 (12.5) | 0.566 | 91 (9.9) | 137 (10.7) | 0.573 |

| Renal insufficiency | 51 (10.7) | 47 (6.8) | 0.018 | 65 (7.1) | 110 (8.6) | 0.207 |

| Thrombocytopaenia | 15 (3.2) | 14 (2.1) | 0.235 | 16 (1.8) | 24 (1.9) | 0.900 |

| History of major bleeding | 19 (4.0) | 25 (3.6) | 0.744 | 27 (2.9) | 32 (2.5) | 0.517 |

| Number of HBR criteria | 1.6±0.7 | 1.5±0.7 | 0.074 | 1.5±0.7 | 1.5±0.7 | 0.246 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Age, years | 75.6±9.3 | 74.9±9.4 | 0.191 | 76.2±7.8 | 75.2±9.4 | 0.010 |

| Female | 170 (35.8) | 260 (37.7) | 0.499 | 283 (30.9) | 441 (34.4) | 0.084 |

| Race | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.5) | 0.103 |

| Asian | 56 (17.8) | 18 (2.6) | <0.001 | 70 (10.7) | 27 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Black or African American | 18 (5.7) | 47 (6.8) | 0.516 | 18 (2.7) | 70 (5.5) | 0.007 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.4) | 0.174 |

| White | 238 (75.8) | 597 (86.6) | <0.001 | 569 (86.6) | 1,142 (89.0) | 0.120 |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity | 55 (12.2) | 18 (2.6) | <0.001 | 83 (9.6) | 38 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 405 (85.3) | 626 (90.9) | 0.003 | 774 (84.4) | 1,145 (89.2) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 309 (65.1) | 580 (84.2) | <0.001 | 630 (68.7) | 1,042 (81.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 179 (37.8) | 282 (40.9) | 0.291 | 333 (36.6) | 505 (39.4) | 0.186 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 232 (50.2) | 277 (40.6) | 0.001 | 399 (46.0) | 524 (41.1) | 0.026 |

| Prior PCI | 120 (25.3) | 231 (33.5) | 0.003 | 270 (29.4) | 376 (29.3) | 0.944 |

| Prior CABG | 37 (7.8) | 77 (11.2) | 0.056 | 75 (8.2) | 169 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Prior MI | 93 (19.7) | 131 (19.4) | 0.891 | 134 (14.7) | 186 (14.7) | 0.983 |

| Multivessel disease | 184 (38.7) | 321 (46.6) | 0.008 | 389 (42.4) | 597 (46.5) | 0.056 |

| NSTEMI | 245 (51.6) | 141 (20.5) | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| Unstable angina | 230 (48.4) | 548 (79.5) | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| PARIS bleeding risk score | 6.5±2.3 | 6.1±2.3 | 0.001 | 5.9±2.3 | 6.0±2.3 | 0.381 |

| PARIS bleeding risk score | 6.0 [5.0-8.0] | 6.0 [4.0-8.0] | <0.001 | 6.0 [4.0-8.0] | 6.0 [4.0-8.0] | 0.472 |

| PRECISE-DAPT bleeding risk score | 29.4±12.3 | 26.7±11.6 | <0.001 | 26.8±10.6 | 25.9±11.7 | 0.101 |

| PRECISE-DAPT bleeding risk score | 28.0 [22.0-37.0] | 26.0 [19.0-33.0] | <0.001 | 26.0 [19.0-32.0] | 25.0 [18.0-32.0] | 0.058 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||||

| Number of lesions treated | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 0.945 | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 0.972 |

| Number of vessels treated | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 0.144 | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 0.408 |

| B2/C lesion | 197 (41.5) | 257 (37.3) | 0.151 | 301 (32.8) | 430 (33.5) | 0.735 |

| Bifurcation lesion | 51 (10.7) | 57 (8.3) | 0.154 | 110 (12.0) | 96 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| Radial access | 371 (78.1) | 414 (60.1) | <0.001 | 615 (67.1) | 614 (47.9) | <0.001 |

| Number of stents per subject | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 0.844 | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 1.0 [1.0-1.0] | 0.653 |

| Total stent length, mm | 28.6±15.3 | 26.5±14.5 | 0.021 | 26.5±13.9 | 25.0±13.4 | 0.013 |

| Preprocedural RVD, mm | 3.0±0.5 | 3.0±0.5 | 0.856 | 3.0±0.5 | 3.0±0.5 | 0.190 |

| Preprocedural %DS | 85.0±10.8 | 84.4±9.9 | 0.363 | 81.3±9.9 | 83.7±9.4 | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet therapy at discharge | ||||||

| Aspirin | 424 (89.3) | 644 (93.5) | 0.010 | 708 (77.2) | 1,157 (90.2) | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 368 (77.5) | 551 (80.0) | 0.304 | 836 (91.2) | 1,061 (82.7) | <0.001 |

| Prasugrel | 4 (0.8) | 19 (2.8) | 0.021 | 10 (1.1) | 27 (2.1) | 0.068 |

| Ticagrelor | 103 (21.7) | 120 (17.4) | 0.069 | 71 (7.7) | 197 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Values are n (%), mean±SD or n [IQR]. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DS: diameter stenosis; HBR: high bleeding risk; IQR: interquartile range; MI: myocardial infarction; N/A: not applicable; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PARIS: Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimens in Stented Patients; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PRECISE-DAPT: Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy; RVD: reference vessel diameter; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

ISCHAEMIC OUTCOMES

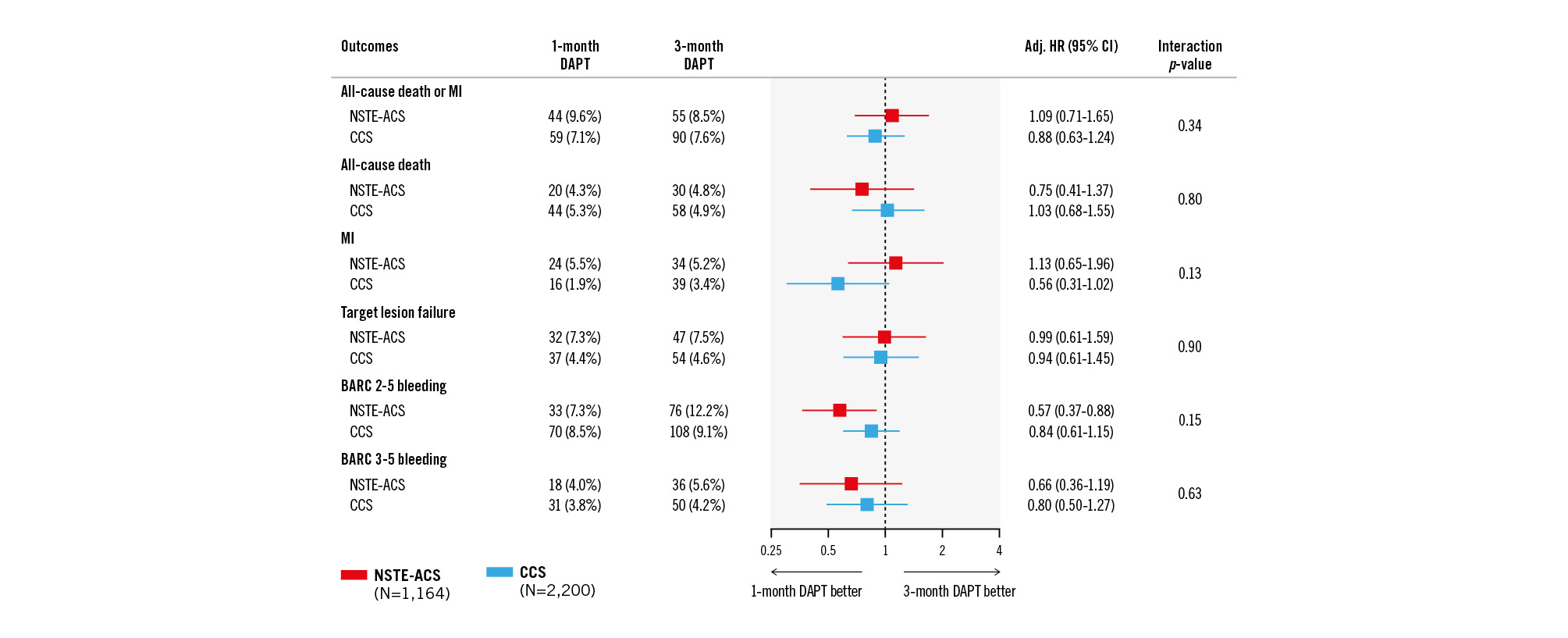

As shown in Supplementary Table 2, NSTE-ACS patients experienced numerically higher rates of the primary endpoint of all-cause death or MI (9.0% vs 7.4%; p=0.074), primarily driven by an increased risk of MI at 1 year (5.3% vs 2.8%; p<0.001). In the NSTE-ACS cohort, the primary endpoint occurred in 9.6% of patients receiving 1-month DAPT and 8.5% of those on 3-month DAPT. After propensity score stratification, the risk of death or MI was similar between the two groups (adjusted [adj.] HR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.71-1.65) (Figure 2). The adjusted risks for the secondary ischaemic endpoints were also similar among NSTE-ACS patients on 1- versus 3-month DAPT, including all-cause death (adj. HR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.41-1.37), MI (adj. HR 1.13, 95% CI: 0.65-1.96), stroke (adj. HR 0.39, 95% CI: 0.12-1.27) and target lesion failure (adj. HR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.61-1.59). Consistent treatment effects were observed in CCS patients for the primary endpoint (adj. HR 0.88, 95% CI: 0.63-1.24) as well as other secondary endpoints, with no significant interaction between clinical presentation and DAPT duration (Figure 2, Table 2).

Figure 2. Clinical outcomes with 1-month versus 3-month DAPT by clinical presentation. Adj. HR: adjusted hazard ratio; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes with 1-month versus 3-month DAPT by clinical presentation.

| NSTE-ACS (N=1,164) | CCS (N=2,200) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | 1-month DAPT (N=475) | 3-month DAPT (N=689) | Adjusted hazard ratio† (95% CI) | p-value | 1-month DAPT (N=917) |

3-month DAPT (N=1,283) |

Adjusted hazard ratio† (95% CI) | p-value | Interactionp-value‡ |

| All-cause death or MI | 44 (9.6) | 55 (8.5) | 1.09 (0.71-1.65) | 0.703 | 59 (7.1) | 90 (7.6) | 0.88 (0.63-1.24) | 0.479 | 0.337 |

| All-cause death | 20 (4.3) | 30 (4.8) | 0.75 (0.41-1.37) | 0.352 | 44 (5.3) | 58 (4.9) | 1.03 (0.68-1.55) | 0.885 | 0.803 |

| Cardiovascular death | 13 (2.8) | 19 (3.1) | 0.90 (0.43-1.90) | 0.783 | 19 (2.3) | 30 (2.6) | 0.84 (0.46-1.54) | 0.580 | 0.798 |

| MI | 24 (5.5) | 34 (5.2) | 1.13 (0.65-1.96) | 0.658 | 16 (1.9) | 39 (3.4) | 0.56 (0.31-1.02) | 0.059 | 0.134 |

| Definite or probable ST | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | N/A | N/A | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 2.32 (0.50-10.81) | 0.282 | 0.992 |

| Stroke | 4 (0.9) | 12 (1.9) | 0.39 (0.12-1.27) | 0.118 | 7 (1.0) | 21 (1.8) | 0.43 (0.18-1.05) | 0.064 | 0.959 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 3 (0.7) | 10 (1.6) | 0.32 (0.08-1.22) | 0.095 | 6 (0.9) | 20 (1.7) | 0.37 (0.14-0.95) | 0.040 | 0.964 |

| Target lesion failure | 32 (7.3) | 47 (7.5) | 0.99 (0.61-1.59) | 0.957 | 37 (4.4) | 54 (4.6) | 0.94 (0.61-1.45) | 0.775 | 0.897 |

| Target lesion revascularisation | 6 (1.4) | 16 (2.6) | 0.56 (0.21-1.50) | 0.250 | 12 (1.5) | 10 (0.8) | 1.77 (0.74-4.23) | 0.198 | 0.079 |

| Target vessel revascularisation | 9 (2.3) | 23 (3.7) | 0.56 (0.25-1.26) | 0.162 | 20 (2.6) | 23 (1.9) | 1.35 (0.72-2.51) | 0.347 | 0.123 |

| BARC 2-5 bleeding | 33 (7.3) | 76 (12.2) | 0.57 (0.37-0.88) | 0.011 | 70 (8.5) | 108 (9.1) | 0.84 (0.61-1.15) | 0.270 | 0.150 |

| BARC 3-5 bleeding | 18 (4.0) | 36 (5.6) | 0.66 (0.36-1.19) | 0.166 | 31 (3.8) | 50 (4.2) | 0.80 (0.50-1.27) | 0.341 | 0.632 |

| Data are presented as number of events (%). The percentages represent Kaplan-Meier rates between 1 and 12 months after the index procedure. †Propensity-stratified outcomes according to sex, baseline serum creatinine, anticoagulation therapy, history of stroke, history of major bleeding, baseline platelet, baseline haemoglobin, BMI, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, prior PCI, prior CABG, prior MI, multivessel disease, diabetes, B2/C lesion, total lesion length, mean preprocedural RVD, mean preprocedural %DS, bifurcation lesion, number of lesions treated, number of vessels treated, number of stents, total stent length, P2Y12 inhibitor at discharge, PARIS risk score for major bleeding, and PRECISE-DAPT risk score for bleeding. ‡P-value is obtained from the interaction test between clinical presentation and DAPT treatment. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CI: confidence interval; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DS: diameter stenosis; MI: myocardial infarction; N/A: not applicable; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PARIS: Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimens in Stented Patients; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PRECISE-DAPT: Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy; RVD: reference vessel diameter; ST: stent thrombosis | |||||||||

BLEEDING OUTCOMES

The 1-year incidence of the key secondary endpoint of BARC Type 2 to 5 bleeding was similar between NSTE-ACS and CCS patients (10.1% vs 8.9%; p=0.213) (Supplementary Table 2). In the NSTE-ACS cohort, BARC 2-5 bleeding occurred in 7.3% of those on 1-month DAPT versus 12.2% on 3-month DAPT, with a significant risk reduction after propensity score stratification (adj. HR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.37-0.88) (Figure 2). Similar treatment effects on BARC 2-5 bleeding were observed in CCS patients for 1 versus 3 months of DAPT (adj. HR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.61-1.15; p-interaction=0.15). The risk of major BARC 3-5 bleeding did not differ between treatment arms for either NSTE-ACS (adj. HR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.36-1.19) and CCS patients (adj. HR 0.80, 95% CI: 0.50-1.27; p-interaction=0.63) (Figure 2, Table 2).

EXPLORATORY ANALYSES

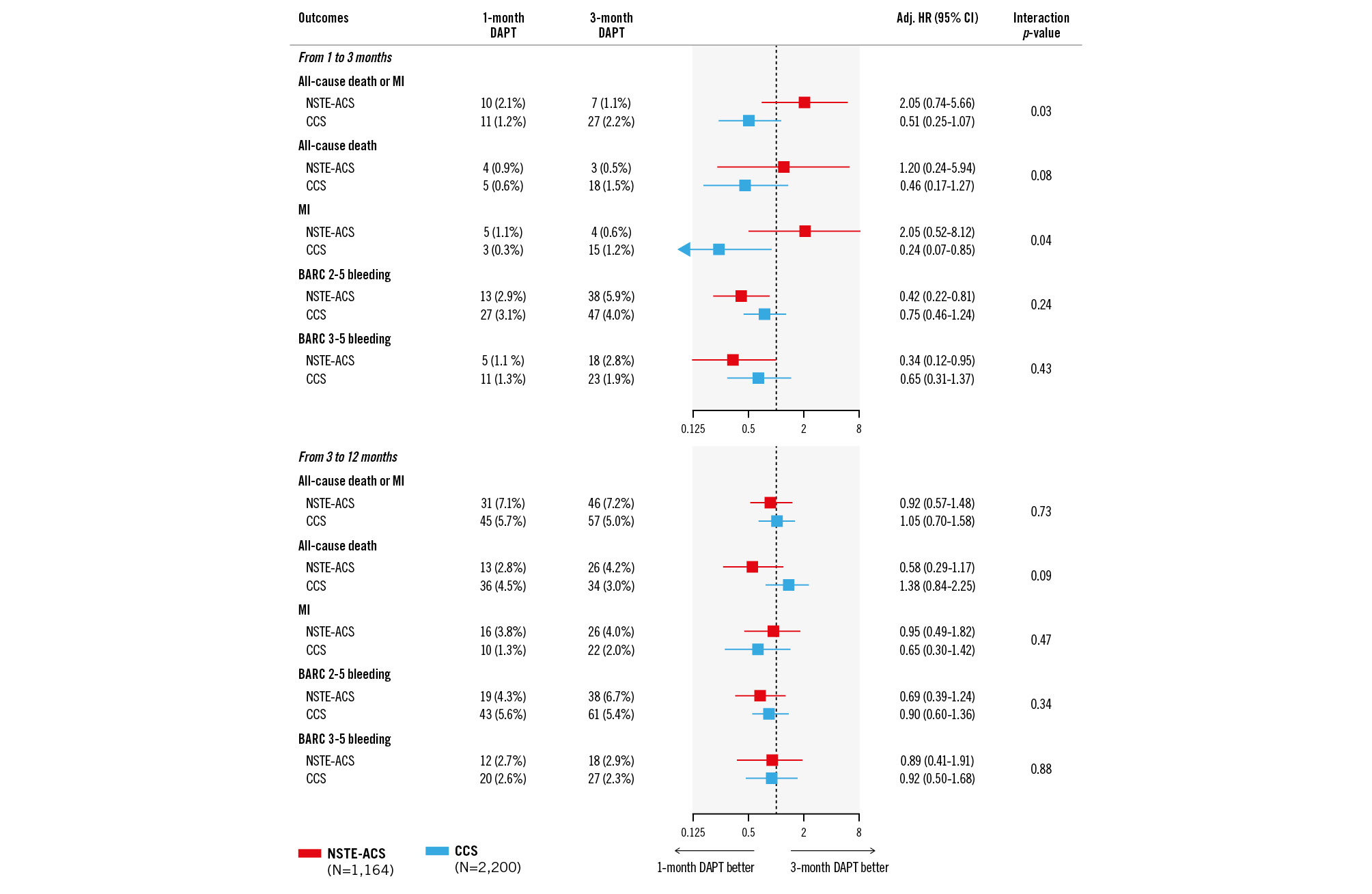

Landmark analyses between 1 and 3 months (Figure 3) showed a numerical increase in the risk of death or MI with 1- versus 3-month DAPT among NSTE-ACS (adj. HR 2.05, 95% CI: 0.74-5.66) but not CCS patients (adj. HR 0.51, 95% CI: 0.25-1.07; p-interaction=0.032). This finding was primarily driven by differences in the risk of MI (p-interaction=0.040) and to a lesser extent the risk of death (p-interaction=0.076). Conversely, between 3 and 12 months when both arms were on aspirin monotherapy, treatment effects on death or MI were consistent between CCS and NSTE-ACS patients (p-interaction=0.726).

The bleeding risk at 3 months was lower with 1- versus 3-month DAPT without evidence of heterogeneity by clinical presentation (p-interaction=0.237 for BARC 2-5; p-interaction=0.429 for BARC 3-5). No significant differences between treatment arms were observed beyond 3 months up to 1 year.

In the analysis by NSTE-ACS subtypes (Table 3), there was no signal of treatment effect modification according to presentation for NSTEMI, unstable angina, or CCS, with respect to both ischaemic and bleeding events.

In the sensitivity analysis excluding patients on oral antiÂcoagulation (Table 4), the risk of the primary and key secondary endpoints with 1- versus 3-month DAPT according to clinical presentation remained consistent with the primary analysis. A significant interaction between clinical presentation and DAPT duration was observed for MI (p-interaction=0.012), with a lower risk associated with 1-month DAPT in CCS but not NSTE-ACS patients.

Figure 3. Landmark analysis at 3 months. Adj. HR: adjusted hazard ratio; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Table 3. Outcomes with 1-month versus 3-month DAPT by NSTE-ACS subtypes.

| CCS (N=2,200) | UA (N=778) | NSTEMI (N=386) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | 1-month DAPT (N=917) |

3-month DAPT (N=1,283) |

Adjustedhazard ratio†(95% CI) | p-value | 1-month DAPT (N=230) |

3-month DAPT (N=548) |

Adjustedhazard ratio†(95% CI) | p-value | 1-month DAPT (N=245) |

3-month DAPT (N=141) |

Adjustedhazard ratio†(95% CI) | p-value | Interactionp-value‡ |

| All-cause death or MI | 59 (7.1) | 90 (7.6) | 0.88 (0.63-1.24) | 0.479 | 15 (7.4) | 41 (8.1) | 0.78 (0.42-1.44) | 0.421 | 29 (11.9) | 14 (10.2) | 1.19 (0.61-2.33) | 0.607 | 0.895 |

| All-cause death | 44 (5.3) | 58 (4.9) | 1.03 (0.68-1.55) | 0.885 | 10 (4.5) | 21 (4.3) | 0.95 (0.43-2.11) | 0.909 | 10 (4.1) | 9 (6.6) | 0.46 (0.18-1.18) | 0.106 | 0.851 |

| MI | 16 (1.9) | 39 (3.4) | 0.56 (0.31-1.02) | 0.059 | 5 (3.0) | 27 (5.1) | 0.43 (0.16-1.16) | 0.097 | 19 (8.0) | 7 (5.2) | 2.00 (0.81-4.93) | 0.133 | 0.654 |

| BARC 2-5 bleeding | 70 (8.5) | 108 (9.1) | 0.84 (0.61-1.15) | 0.269 | 15 (6.9) | 58 (11.8) | 0.54 (0.30-0.98) | 0.042 | 18 (7.6) | 18 (13.7) | 0.56 (0.28-1.13) | 0.104 | 0.253 |

| BARC 3-5 bleeding | 31 (3.8) | 50 (4.2) | 0.80 (0.50-1.27) | 0.341 | 10 (4.6) | 24 (4.7) | 0.81 (0.37-1.76) | 0.593 | 8 (3.4) | 12 (9.2) | 0.40 (0.16-1.03) | 0.059 | 0.716 |

| Data are presented as number of events (%) unless otherwise specified. The percentages represent Kaplan-Meier rates between 1 and 12 months after the index procedure. †Propensity-stratified outcomes according to sex, baseline serum creatinine, anticoagulation therapy, stroke, history of major bleeding, baseline platelet, baseline haemoglobin, BMI, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, prior PCI, prior CABG, prior MI, multivessel disease, diabetes, B2/C lesion, total lesion length, mean preprocedural RVD, mean preprocedural %DS, bifurcation lesion, number of lesions treated, number of vessels treated, number of stents, total stent length, P2Y12 inhibitor at discharge, PARIS risk score for major bleeding, and PRECISE-DAPT risk score for bleeding. ‡P-value is for the interaction test between DAPT treatment and clinical presentation. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DS: diameter stenosis; MI: myocardial infarction; N/A: not applicable; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PARIS: Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimens in Stented Patients; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PRECISE-DAPT: Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy; RVD: reference vessel diameter; UA: unstable angina | |||||||||||||

Table 4. Sensitivity analysis excluding patients on oral anticoagulation.

| NSTE-ACS (N=668) | CCS (N=1,234) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | 1-month DAPT (N=261) | 3-month DAPT (N=407) | Adjusted hazard ratio† (95% CI) |

p-value | 1-month DAPT (N=487) | 3-month DAPT (N=747) | Adjusted hazard ratio†(95% CI) | p-value | Interactionp-value‡ |

| All-cause death or MI | 28 (11.3) | 28 (7.1) | 1.59 (0.90-2.79) | 0.107 | 32 (6.8) | 51 (7.4) | 0.92 (0.58-1.45) | 0.723 | 0.149 |

| All-cause death | 12 (4.7) | 13 (3.3) | 1.10 (0.47-2.57) | 0.821 | 28 (6.0) | 31 (4.5) | 1.30 (0.77-2.21) | 0.325 | 0.923 |

| Cardiovascular death | 8 (3.2) | 9 (2.3) | 1.05 (0.38-2.95) | 0.921 | 13 (2.7) | 15 (2.2) | 1.24 (0.58-2.67) | 0.583 | 0.928 |

| MI | 16 (6.8) | 21 (5.4) | 1.48 (0.74-2.97) | 0.270 | 4 (0.8) | 25 (3.7) | 0.25 (0.09-0.73) | 0.011 | 0.012 |

| Definite or probable ST | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | N/A | N/A | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) | 0.69 (0.07-6.70) | 0.745 | N/A |

| Stroke | 3 (1.2) | 7 (1.8) | 0.90 (0.21-3.78) | 0.883 | 4 (0.9) | 13 (1.9) | 0.42 (0.13-1.33) | 0.140 | 0.686 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 2 (0.8) | 6 (1.6) | 0.62 (0.11-3.36) | 0.577 | 4 (0.9) | 13 (1.9) | 0.42 (0.13-1.33) | 0.140 | 0.911 |

| Target lesion failure | 20 (8.3) | 28 (7.3) | 1.13 (0.61-2.10) | 0.697 | 20 (4.2) | 30 (4.3) | 1.00 (0.56-1.79) | 0.997 | 0.812 |

| Target lesion revascularisation | 2 (0.8) | 10 (2.8) | 0.33 (0.07-1.61) | 0.171 | 7 (1.5) | 7 (1.0) | 1.52 (0.52-4.47) | 0.445 | 0.091 |

| Target vessel revascularisation | 5 (2.3) | 15 (4.1) | 0.53 (0.18-1.54) | 0.240 | 13 (2.9) | 16 (2.3) | 1.36 (0.64-2.87) | 0.425 | 0.167 |

| BARC 2-5 bleeding | 14 (5.7) | 33 (8.6) | 0.61 (0.31-1.19) | 0.145 | 27 (5.8) | 48 (6.9) | 0.78 (0.48-1.28) | 0.327 | 0.542 |

| BARC 3-5 bleeding | 6 (2.4) | 14 (3.6) | 0.61 (0.22-1.68) | 0.336 | 11 (2.4) | 22 (3.2) | 0.70 (0.33-1.48) | 0.346 | 0.845 |

| Data are presented as number of events (%) unless otherwise specified. The percentages represent Kaplan-Meier rates between 1 and 12 months after the index procedure. †Propensity-stratified outcomes according to sex, baseline serum creatinine, anticoagulation therapy, stroke, history of major bleeding, baseline platelet, baseline haemoglobin, BMI, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, prior PCI, prior CABG, prior MI, multivessel disease, diabetes, B2/C lesion, total lesion length, mean preprocedural RVD, mean preprocedural %DS, bifurcation lesion, number of lesions treated, number of vessels treated, number of stents, total stent length, P2Y12 inhibitor at discharge, PARIS risk score for major bleeding, PRECISE-DAPT risk score for bleeding. ‡P-value is obtained from the interaction test between clinical presentation and DAPT after applying multiple imputation and propensity score stratification. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DS: diameter stenosis; MI: myocardial infarction; N/A: not applicable; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PARIS: Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimens in Stented Patients; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PRECISE-DAPT: Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy; RVD: reference vessel diameter; ST: stent thrombosis | |||||||||

Discussion

In a large cohort of HBR patients undergoing successful, non-complex PCI with a cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent, who had been adherent to treatment and free from ischaemic events while on DAPT, discontinuation of the P2Y12 inhibitor after 1 month compared with 3 months was associated with a similar ischaemic risk and reduced actionable bleeding events, irrespective of clinical presentation at the time of PCI. Although NSTE-ACS compared with CCS presentation was associated with a 2-fold higher risk of MI at 12-month follow-up, extending DAPT to 3 months did not appear to confer an extra ischaemic protection across the spectrum of HBR patients. Conversely, the incidence of BARC Type 2-5 bleeding was comparable between NSTE-ACS and CCS patients, with both subgroups deriving consistent benefit from 1-month DAPT (Central illustration).

The XIENCE Short DAPT programme was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of two abbreviated DAPT regimens (1 month in XIENCE 28 and 3 months in XIENCE 90) which have previously been shown to be non-inferior to a historical cohort of patients receiving 6 to 12 months of DAPT for the primary endpoint of death or MI16. Other stent platforms have proven similar safety with a DAPT duration as short as 3 months but, at variance with our study, failed to include ACS patients22. In a more recent analysis from XIENCE Short DAPT involving the overall study population, DAPT for 1 month compared with 3 months was associated with a similar ischaemic risk and lower bleeding complications at 1-year follow-up17. The present substudy extends these observations to HBR patients presenting with NSTE-ACS, in whom bleeding avoidance strategies that do not compromise antithrombotic efficacy are most challenging.

Real-world registries have reported on the prevalence and prognostic impact of HBR conditions in relation to clinical presentation at the time of PCI2324. Advanced age, oral anticoagulation, and anaemia were the most frequent HBR conditions, the latter being more prevalent among NSTE-ACS than CCS patients in our study, together with higher PRECISE-DAPT and PARIS bleeding risk scores. ACS presentation, per se, has previously been found to be an independent predictor of bleeding, with a graded relationship across ACS subtypes: highest risk after a STEMI and lowest in case of unstable angina23. Although we observed a similar incidence of BARC 2-5 bleeding among NSTE-ACS and CCS patients (10.1% vs 8.9%), the analysis by NSTE-ACS subtypes highlighted a numerical trend towards a higher bleeding risk in those with an NSTEMI. Therefore, the finding of a proportionally larger bleeding risk reduction with 1- versus 3-month DAPT among NSTEMI patients relative to those with unstable angina or CCS is of high clinical relevance and warrants prospective confirmation from dedicated studies.

Overall, our findings are in keeping with those from the MASTER DAPT trial, which randomised HBR patients undergoing PCI with a biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting stent between 1-month versus standard (≥3-month) DAPT. In line with the main trial results, the subgroups presenting with and without an acute or recent MI (i.e., within the past 12 months), including STEMI, derived a consistent net benefit from 1-month DAPT, with similar cardiovascular events (prior MI: 7.6% vs 8.7% and no prior MI: 5.0 vs 4.5%) and reduced BARC 2, 3, or 5 bleeding (prior MI: 6.2% vs 9.3% and no prior MI: 6.7 vs 9.4%)11. Notably, the study designs of XIENCE Short DAPT and MASTER DAPT were different with respect to stent platform, ACS subgroup definition, and single antiplatelet regimen following DAPT (75% of patients in MASTER DAPT received P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy). Moreover, in our landmark analysis, the effects of 1- versus 3-month DAPT on the risk of death or MI was inconsistent among NSTE-ACS and CCS patients between 1 and 3 months. It is remarkable, however, that this finding was driven by a relatively small number of events, and there was no such signal of heterogeneity on the 1-year outcomes. These differences notwithstanding, taken together, both trials provide encouraging data on the safety of 1 month compared with ≥3 months of DAPT after PCI, regardless of clinical presentation.

An important caveat of all short DAPT studies relates to the monotherapy regimen based on either aspirin or P2Y12 inhibitors following DAPT discontinuation. The XIENCE Short DAPT protocol required the use of aspirin monotherapy after the initial DAPT course. However, recent evidence supports the superiority of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy over aspirin for long-term secondary prevention in subjects with established coronary artery disease25. This observation may partly explain the heterogeneity in treatment effects seen in our landmark and sensitivity analyses where 1-month DAPT (followed by aspirin) was associated with less favourable outcomes, especially MI, after an NSTE-ACS. In fact, a growing body of evidence suggests a potential role of early aspirin withdrawal followed by potent P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy among those subjects in whom both bleeding and ischaemic risks are of concern2627. Owing to their double-sided risk, HBR-ACS patients may be ideal candidates for such an approach. In the TWILIGHT trial, subjects at high risk for ischaemic and bleeding events who had completed a 3-month course of aspirin plus ticagrelor post-PCI were randomised to ticagrelor monotherapy or ticagrelor plus aspirin for an additional 12 months28. Surprisingly, the NSTE-ACS subgroup derived the greatest net benefit from this monotherapy regimen10. To be enrolled in the trial, however, patients had to be deemed eligible for a long-term DAPT with ticagrelor, which resulted in only 17% of them being classified as HBR29. Other trials on short DAPT followed by potent P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy have yielded consistent results12. However, controversies persist with regard to clopidogrel monotherapy, especially in an ACS setting. In the STOPDAPT-2 ACS Study, which enrolled 4,196 patients mostly at low-to-intermediate bleeding risk who underwent PCI for an ACS using the same cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent, 1-month DAPT followed by clopidogrel monotherapy failed to attest non-inferiority to 12-month DAPT for the primary endpoint of net clinical benefit, with a numerical increase in cardiovascular events despite less bleeding13. Whether a strategy of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy holds the promise of preserving ischaemic protection while effectively reducing bleeding after only 1 month of DAPT, or even omitting DAPT, among HBR patients is yet to be proven in large-scale studies303132.

Central illustration. Outcomes of 1- versus 3-month DAPT in high bleeding risk patients undergoing PCI according to clinical presentation. High bleeding risk patients who underwent successful, non-complex PCI with a cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent were enrolled in the XIENCE Short DAPT programme and received 1-month DAPT (XIENCE 28 Global and 28 USA) or 3-month DAPT (XIENCE 90) followed by aspirin monotherapy. Patients who had been adherent to treatment and free from MI, repeat coronary revascularisation, stroke, or stent thrombosis at 1 month post-PCI were included. In this subgroup analysis, the effects of 1- versus 3-month DAPT were evaluated using propensity score stratification according to clinical presentation (NSTE-ACS or CCS). Adj. HR: adjusted hazard ratio; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; HBR: high bleeding risk; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Limitations

The non-randomised design introduces the risk for residual unmeasured confounding despite efforts to adjust through propensity score stratification using rigorous statistical methodology.

The present subgroup analysis as well as the comparison between 1 and 3 months of DAPT were prespecified, but the propensity score analysis of the pooled XIENCE 28 and 90 population was not. In XIENCE 90, there was no scheduled follow-up at 1 month, and event-free patients were derived retrospectively to match the corresponding cohort of patients on 1-month DAPT from XIENCE 28. The XIENCE Short DAPT programme included only patients who had undergone successful PCI of non-complex target lesion anatomy, with exclusive use of the same cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent platform. Those with STEMI were excluded, and therefore, our findings do not apply to patients who did not meet the study enrolment criteria nor those who were not event free at the predefined time points. Moreover, the HBR criteria used in XIENCE Short DAPT partially differ from those proposed by the Academic Research Consortium consensus, which became available after both XIENCE 28 and 90 had started enrolling1533. Lastly, our findings must be considered hypothesis-generating. As with most subgroup analyses, the present study was likely underpowered to detect clinically relevant differences in ischaemic and bleeding outcomes, and the wide CIs do not conclusively rule out a potential for harm with either of the two DAPT strategies.

Conclusions

Among HBR patients undergoing non-complex PCI with an everolimus-eluting stent and enrolled in the XIENCE Short DAPT programme, about one in three presented with NSTE-ACS. DAPT for 1 month, compared with DAPT for 3 months followed by aspirin monotherapy, was associated with a similar 1-year risk of death or MI and lower bleeding risk, irrespective of clinical presentation.

Impact on daily practice

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) presentation is known to be associated with high rates of recurrent ischaemic and bleeding events. A short dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) duration has been proposed for high bleeding risk (HBR) patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); however, there is little evidence in support of this practice after an ACS. Our analysis from the XIENCE Short DAPT programme suggests that, among HBR patients undergoing non-complex PCI for either non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS) or chronic coronary syndrome, 1-month compared with 3-month DAPT is associated with a similar ischaemic risk and reduced bleeding. These findings support the safety and efficacy of a very short DAPT duration as a bleeding avoidance strategy, irrespective of clinical presentation. Future studies should explore the optimal antithrombotic agent, whether aspirin or P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy, for long-term secondary prevention after early DAPT discontinuation among HBR patients.

Funding

The study was sponsored by Abbott.

Conflict of interest statement

D. Cao reports consulting fees from Terumo. P. Vranckx has received grants and/or personal fees from AstraZeneca, Terumo, Abbott, Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer AG, and CSL Behring. M. Valgimigli reports grants and personal fees from Terumo; and has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Alvimedica/CID, Abbott, Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer, CoreFlow, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Universität Basel - Departement Klinische Forschung, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb SA, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Vesalio, Novartis, Chiesi, and PhaseBio, outside the submitted work. D.J. Angiolillo has received consulting fees or honoraria from Abbott, Amgen, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Haemonetics, Janssen, Merck, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, and The Medicines Company; and has received payments for participation in review activities from CeloNova and St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), outside the present work; he also declares that his institution has received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, CeloNova, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Matsutani Chemical Industry Co., Merck, Novartis, Osprey Medical, Renal Guard Solutions, and Scott R. MacKenzie Foundation. S. Bangalore has received grants from Abbott; and personal fees from Abbott, Biotronik, Amgen, and Pfizer. D.L. Bhatt discloses the following relationships - advisory board: ANGIOWave, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, High Enroll, Janssen, Level Ex, McKinsey, Medscape Cardiology, Merck, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences, and Stasys; board of directors: ANGIOWave (stock options), Boston VA Research Institute, Bristol-Myers Squibb (stock), DRS.LINQ (stock options), High Enroll (stock), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, and Tobesoft; Chair: inaugural Chair, American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; consultant: Broadview Ventures, and Hims; data monitoring committees: Acesion Pharma, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Boston Scientific (Chair, PEITHO trial), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards Lifesciences), Contego Medical (Chair, PERFORMANCE 2), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo; for the ABILITY-DM trial, funded by Concept Medical), Novartis, Population Health Research Institute, and Rutgers University (for the NIH-funded MINT Trial); honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Chair, ACC Accreditation Oversight Committee), Arnold and Porter law firm (work related to Sanofi/Bristol-Myers Squibb clopidogrel litigation), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor-in-Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group (clinical trial steering committees), CSL Behring (AHA lecture), Cowen and Company, Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), K2P (Co-Chair, interdisciplinary curriculum), Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), MJH Life Sciences, Oakstone CME (Course Director, Comprehensive Review of Interventional Cardiology), Piper Sandler, Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees), and Wiley (steering committee); other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); patent: Sotagliflozin (named on a patent for sotagliflozin assigned to Brigham and Women’s Hospital who assigned to Lexicon; neither he nor Brigham and Women’s Hospital receives any income from this patent); research funding: Abbott, Acesion Pharma, Afimmune, Aker Biomarine, Alnylam, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beren, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Chiesi, CinCor, Cleerly, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Faraday Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Garmin, HLS Therapeutics, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Janssen, Javelin, Lexicon, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Merck, Moderna, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka, Owkin, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Recardio, Regeneron, Reid Hoffman Foundation, Roche, Sanofi, Stasys, Synaptic, The Medicines Company, Youngene, and 89bio; royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Braunwald’s Heart Disease); site co-investigator: Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, Endotronix, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Philips, SpectraWAVE, Svelte, and Vascular Solutions; trustee: American College of Cardiology; and unfunded research: FlowCo, Takeda. J. Hermiller reports consulting and proctoring fees from Abbott and Edwards Lifesciences; and consulting fees from Medtronic. R.R. Makkar has received research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific; has served as national Principal Investigator for Portico (Abbott) and ACURATE (Boston Scientific) U.S. investigation device exemption trials; has received personal proctoring fees from Edwards Lifesciences; and has received travel support from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott, and Boston Scientific. F. Neumann reports grants and/or personal fees from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, Pfizer, Biotronik, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Boston Scientific, and Ferrer. R. Toelg reports speaker honoraria from Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Biotronik. A. Maksoud is a speakers bureau member for Abbott Vascular, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and he has received research grants from Abbott and Edwards Lifesciences. B.M. Chehab has received research grants from Edwards Lifesciences and Abbott; and speaker honoraria and/or personal fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott, and Biotronik. J.W. Choi has received consulting fees from Medtronic. G. Campo has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, Medis, SMT, and Siemens. J. de la Torre Hernández has received grants/research supports from Abbott, Biosensors, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Amgen; and he has received honoraria or consultation fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Biotronik, AstraZeneca, and Daiichi Sankyo. M.W. Krucoff reports grants and/or personal fees from Abbott, Biosensors, Boston Scientific, CeloNova, Medtronic, OrbusNeich, and Terumo. V. Kunadian has received personal fees/honoraria from Bayer, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Amgen, and Daiichi Sankyo. O. Varenne has received personal fees/honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Biosensors, and AstraZeneca. S. Windecker reports research, travel or educational grants to the institution without personal remuneration from Abbott, Abiomed, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Braun, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardinal Health, CardioValve, Cordis Medical, Corflow Therapeutics, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Farapulse Inc., Fumedica, Guerbet, Idorsia, Inari Medical, InfraRedx, Janssen Cilag, Johnson & Johnson, MedAlliance, Medicure, Medtronic, Merck, Miracor Medical, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Organon, OrPha Suisse, Pharming Tech, Pfizer, Polares, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Sinomed, Terumo, Vifor, and V-Wave; he served as an advisory board member and/or member of the steering/executive group of trials funded by Abbott, Abiomed, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Edwards Lifesciences, MedAlliance, Medtronic, Novartis, Polares, Recardio, Sinomed, Terumo, and V-Wave, with payments to the institution but no personal payments; he is also a member of the steering/executive committee group of several investigator-initiated trials that receive funding by industry without impact on his personal remuneration. R. Mehran reports institutional research grants from Abbott, Abiomed, Applied Therapeutics, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardiawave, CellAegis, CERC, Chiesi, Concept Medical, CSL Behring, DSI, Insel Gruppe AG, Medtronic, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, OrbusNeich, Philips, Transverse Medical, and Zoll; personal fees from ACC, Boston Scientific, California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), Cine-Med Research, Janssen, WebMD, and SCAI; consulting fees paid to the institution from Abbott, Abiomed, AM-Pharma, Alleviant Medical, Bayer, Beth Israel Deaconess, Cardiawave, CeloNova, Chiesi, Concept Medical, DSI, Duke University, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Novartis, and Philips; equity <1% in Applied Therapeutics, Elixir Medical, STEL, and CONTROLRAD (spouse); Scientific Advisory Board for AMA, and Biosensors (spouse). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.