Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

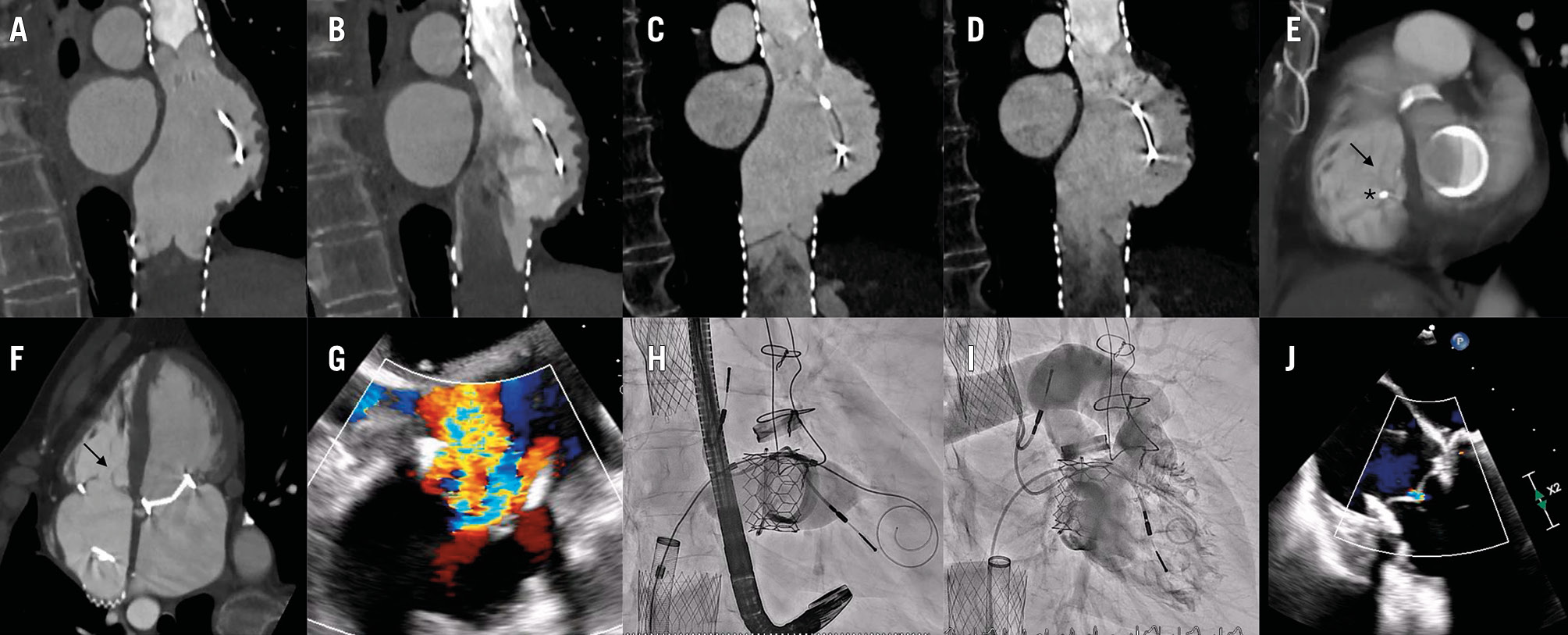

A 73-year-old female presented with symptomatic, massive tricuspid regurgitation (TR). The patient had prior rheumatic valve disease with mechanical aortic and mitral valves, tricuspid annuloplasty with a 32 mm MC3 ring (Edwards Lifesciences) and a dual-chamber pacemaker. Computed tomography showed an area of 580 mm2 and a maximum internal diameter of 32 mm of the annuloplasty ring. After the Heart Team review, she was deemed unsuitable for edge-to-edge repair and, given the incomplete rigid ring and pacing lead, was considered at risk of paravalvular leak along the open segment of the ring using a 29 mm balloon-expandable valve. Hence, bicaval valve implantation (CAVI) using 25 mm and 31 mm TricValves (Products & Features) was performed (Figure 1A, Moving image 1). Four years later, she developed progressive dyspnoea and peripheral oedema. Computed tomography showed structural valve deterioration (SVD) of both the superior and inferior vena cava prostheses, with stuck leaflets resulting in a large coaptation gap and severe intraprosthetic regurgitation (Figure 1B-Figure 1C-Figure 1D, Moving image 2). There were no signs of leaflet thrombosis or endocarditis. Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) showed massive TR and a large coaptation gap (Figure 1E), and tricuspid valve-in-ring with an extra-large balloon-expandable valve was planned. The procedure was performed under TOE guidance. To prevent interaction between both prostheses, a 26 Fr long DrySeal sheath (Gore Medical) was advanced through the degenerated inferior caval prosthesis into the right atrium, and, using an 8.5 Fr Agilis NxT sheath (Abbott), a SAFARI² wire (Boston Scientific) was inserted into the right ventricle. Under rapid pacing, a 32 mm Myval valve (Meril Life Sciences) was successfully implanted (Figure 1F-Figure 1G-Figure 1H, Moving image 3, Moving image 4). At 6-month follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic, with trace residual TR and stable pacing thresholds and impedance (Figure 1I, Figure 1J). Despite favourable midterm outcomes with CAVI, long-term data are lacking1. Prior cases of CAVI dysfunction have been limited to thrombosis or endocarditis, but SVD has been scarcely reported23. Leaflet thickening and restriction without thrombus suggested fibrosis as the most likely mechanism of SVD in this patient, potentially mediated by low leaflet shear stress in a low-pressure venous conduit which may promote flow stagnation and inflammation. The present case highlights the need for longer imaging follow-up and shows the feasibility of a percutaneous orthotopic tricuspid intervention through a degenerated caval prosthesis. Noteworthily, lead entrapment may result in late complications and requires close surveillance. Decision-making should carefully consider the integration of upcoming technologies and avoid imposing unnecessary barriers that could hinder their use.

Figure 1. Pre- and intraprocedural imaging. A,B) CT scans (2020) showing appropriate competence of both caval valves (A: closed valve; B: open valve). C,D) CT scans (2024) showing bicaval prosthesis dysfunction with severe intraprosthetic regurgitation (C: stuck leaflet during closure; D: open valve). E,F) CT scans (2024) showing a large tricuspid coaptation gap (arrow) and lead at the posteroseptal commissure (asterisk). G) TOE long-axis view (150º) showing massive TR. H) Valve-in-ring implantation of a 32 mm Myval valve (Meril Life Sciences). I,J) Final trace central TR. CT: computed tomography; TOE: transoesophageal echocardiography; TR: triscuspid regurgitation

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Moving image 1. 4D-CT showing normal caval valve function.

Moving image 2. 4D-CT showing bicaval prosthesis dysfunction with severe intraprosthetic regurgitation

Moving image 3. Valve-in-ring implantation.

Moving image 4. Right ventriculography showing trace residual MR.