Introduction

Antiplatelet monotherapy is the standard of care for secondary prevention after an initial course of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients with acute coronary syndrome or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Aspirin has long been the drug of choice for this purpose and is still recommended under Class I by guidelines. However, randomised trials and meta-analyses suggested a potential benefit with clopidogrel, a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor. As such, a Class IIb recommendation supporting the use of clopidogrel for long-term secondary prevention has been yielded by the latest guidelines. Nevertheless, limitations regarding enrolled populations and study design should be considered when interpreting such findings. Whether current evidence is enough to advocate the routine use of clopidogrel instead of aspirin for long-term secondary prevention is a matter for debate.

Pros

Hyo-Soo Kim, MD; Jeehoon Kang, MD

Medical treatment including antithrombotic therapy after PCI is essential in preventing recurrence. After the initial period of intensive antithrombotic therapy (usually DAPT), antiplatelet monotherapy is used as secondary prevention.

Guidelines “still” state that aspirin should be the first-line antiplatelet agent for secondary prevention1. Aspirin has long been the therapeutic foundation of secondary prevention, but numerous evidence has accumulated to give this agent a nice retirement. The evidence that supports aspirin as the treatment of choice for secondary prevention is based on studies performed more than 4 decades ago. In the early clinical studies, PCI was not performed in its modern form, and patients in these studies were those with a history of previous vascular events. Even in these studies, many individual trials were inconclusive, while a series of meta-analyses concluded that aspirin is an effective agent for secondary prevention2. If we were to review these studies from the current appraisal point of view, this conclusion would be a nuance that would be underappreciated.

During the initial era of PCI, DAPT was required for 1 year after PCI to prevent ischaemic complications. But this was always counteracted by the trade-off with an increased bleeding risk. Along with the increased concerns about aspirinÂ-related bleeding, and with the presence of a suitable alternative antithrombotic agent, the P2Y12 inhibitor, many trials examined the efficacy of aspirin-free strategies after PCI. These trials consecutively demonstrated that aspirin discontinuation did not compromise patients with excessive ischaemic risk, while it reduced the bleeding risk. Cumulative evidence led to questions as to whether aspirin is necessary in the chronic phase after PCI. Although the clinical scenario may be slightly different, the efficacy of aspirin in the primary prevention window has been negatively proven by 3 randomised clinical trials, leading to a downgrade of previous endorsements in current guidelines1. Overall, many studies have shown that the anti-ischaemic role of aspirin in primary and secondary prevention may have diminished as compared to historical studies.

For direct comparison of aspirin versus clopidogrel in the secondary prevention setting, 2 large-scale studies have provided evidence for the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel. The CAPRIE trial enrolled patients at risk for vascular events; it compared the antiplatelet effect across a wide range of clinical indications3. Although the dose of aspirin was higher (325 mg once daily) than average contemporary dosing, this study showed that clopidogrel was moderately more effective than aspirin in reducing adverse cardiovascular events. Subsequently, in the era of PCI, the HOST-EXAM trial performed a head-to-head comparison of aspirin versus clopidogrel in patients who were event-free under DAPT for 6-18 months after PCI and were scheduled to receive single antithrombotic therapy4. The results showed that clopidogrel monotherapy, as compared with aspirin monotherapy, significantly reduced the risk of adverse clinical events, reducing both ischaemic and bleeding composite outcomes. Also, the beneficial effect of clopidogrel monotherapy was sustained up to 6-year follow-up5. These results suggest that clopidogrel targeting the P2Y12 receptor is a more selective drug to effectively prevent thrombosis with less bleeding, while aspirin targeting cyclooxygenase is a non-selective one: weak against thrombosis but disturbing the synthesis of many prostaglandins and the integrity of the mucosal and vascular barrier, leading to easy bleeding.

Collectively, data suggest a reappraisal of the efficacy of lifelong aspirin, while the alternative, clopidogrel, may be more than just an alternative. As we are dealing with lifelong secondary prevention, longer-term outcome studies would provide more concrete evidence, but current evidence “already” seems to be sufficient to consider clopidogrel before aspirin for secondary prevention after PCI.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Cons

Raffaele De Caterina, MD, PhD; Giulio Stefanini, MD, PhD, MSc

Low-dose aspirin has long been a cornerstone in secondary prevention of coronary syndromes and has maintained a Class I, Level of Evidence A recommendation in all the latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines in such conditions. There has recently been a revival, however, of attempts at proposing P2Y12 inhibitors, essentially clopidogrel or ticagrelor, as an alternative to aspirin in long-term monotherapy. We speak about a “revival”, because more than 25 years ago, the CAPRIE trial − which demonstrated a marginal statistical superiority of clopidogrel over aspirin (at that time, given at 325 mg/day) in over 19,000 patients enrolled for a previous myocardial infarction, previous ischaemic stroke or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease – had already proposed clopidogrel as a “winning alternative” to aspirin3. This “statistical superiority” did not lead to changes in guideline or regulatory agency recommendations for at least 4 reasons:

1. In the cohort of post-infarction patients, the relative risk of clopidogrel versus aspirin had been numerically favourable to aspirin;

2. Pooling together the 3 independent cohorts, the absolute benefit on the primary endpoint (a composite of ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction and vascular death) was so minute (5.32% per year for clopidogrel vs 5.83% per year for aspirin) that it translated into an unacceptably high “number needed to treat” (196 patients to treat to prevent one non-fatal event);

3. There was no benefit for clopidogrel on either total or cardiovascular mortality;

4. The lower rate of gastrointestinal bleeding with clopidogrel (0.49% vs 0.71% per year) could well be attributable to the high aspirin dose.

More recently, at a time of contemporary PCI with stenting, the Korean HOST-EXAM Trial showed a lower incidence of myocardial infarction in patients allocated to clopidogrel versus aspirin monotherapy after variable durations of DAPT. However, this relatively small study (n=5,530) also did not show any benefit of clopidogrel over aspirin on cardiovascular or all-cause mortality, and in fact showed a numerical excess of deaths in the clopidogrel arm4.

Ticagrelor is a reversible, biologically active P2Y12 inhibitor (at variance from clopidogrel, not a prodrug), which was found, in the PLATO study, to be superior to clopidogrel in patients treated with aspirin after an acute coronary syndrome. Ticagrelor has therefore been repeatedly proposed as advantageous in monotherapy compared with aspirin. Most studies involving ticagrelor in monotherapy have not, however, had a proper head-to-head aspirin comparator. Such a comparison is available for acute stroke patients in the SOCRATES study, which concluded that ticagrelor was not superior to aspirin in reducing the rate of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death at 90 days6. The GLOBAL LEADERS Study compared a “standard” strategy − with aspirin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor for 1 year − against an abbreviated strategy − with aspirin and ticagrelor for 1 month, followed by ticagrelor only up to 2 years. A landmark analysis at 1 year, comparing aspirin with ticagrelor monotherapy, indicated the superiority of ticagrelor over aspirin with respect to myocardial infarction, but with a higher rate of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) Type 3-5 (major) bleeding and, again, no effect on mortality7.

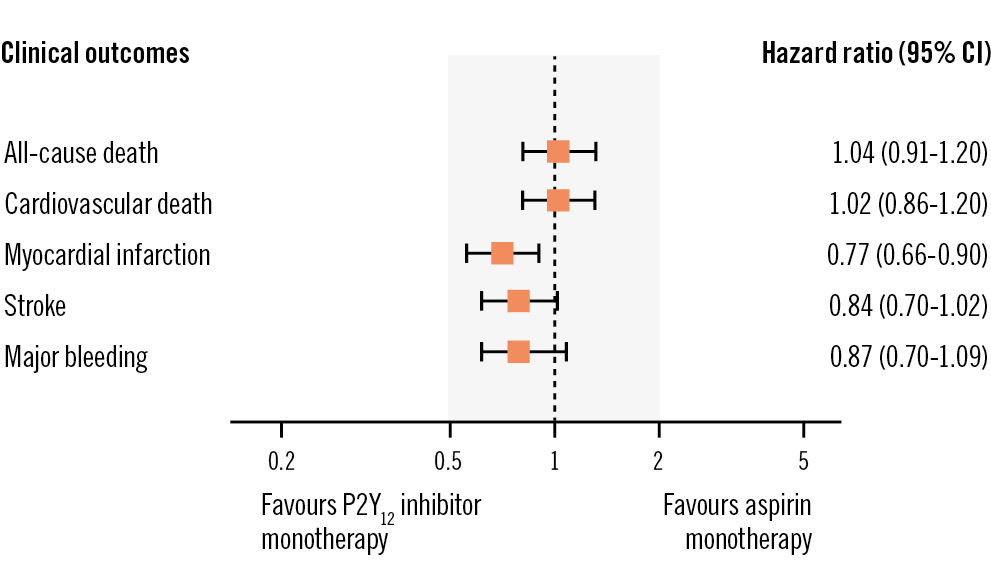

At least 3 further meta-analyses of aspirin versus P2Y12 inhibitors in monotherapy8910 have indeed shown a lower rate of infarction with P2Y12 inhibitors, but these have always confirmed the absence of any effect on (or even a trend towards lower) mortality (Figure 1). Plausible explanations are the clinical irrelevance of infarctions apparently prevented by P2Y12 inhibitors or the emergence of the specific beneficial effects of aspirin on extravascular mortality. The lower number of stent thromboses is largely limited to trials with early DAPT discontinuation, and the purported benefit of P2Y12 inhibitors in terms of gastrointestinal bleeding is largely driven by the inclusion of CAPRIE, with the use of a higher than currently recommended dose of aspirin.

We continue, therefore, on the old, comfortable road that is against changing the current dogma: aspirin should stay as the current standard; neither clopidogrel nor ticagrelor should replace it! We are, with these statements, in good company with the latest 2023 ESC Guidelines on acute coronary syndromes.

Figure 1. Ischaemic and bleeding events in patients receiving aspirin (N=12,147) or a P2Y12 inhibitor (N=12,178) monotherapy in secondary cardiovascular prevention. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given for the various endpoints. In the forest plot, the lower rates of myocardial infarctions associated with P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy and the absence of any effect on (or any trend towards) lowering mortality are emphasised. Data are based on the meta-analysis published by Gragnano et al10.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.