Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Today, emergency endovascular stroke treatment (EST) is the Class Ia-evidenced1 standard of care for acute cerebrovascular occlusions. Despite its unquestionable efficiency, only a minority of the population have effective access to EST due to a shortage of trained teams and capable centres23.

EST requires EST-specific operator training and multispeciality team alignment345. The emergency nature of EST, irregular and unpredictable case presentations and, to some extent, turf protection hinder the “apprenticeship model”. Other current training concepts also have limitations that significantly impact their effectiveness. Three-dimensionally printed bench models can replicate vascular anatomy, but they miss the tissue complexity of cerebral vessels and their susceptibility to, for instance, perforation. High-fidelity simulators may incorporate a virtual environment, but they lack important nuances such as use of real devices, permanent flushing of catheters (a fundamental part of neurointerventions) and continuous drip control to avoid potentially lethal air embolism/thrombus formation. Animal models are poorly applicable to the human cerebral anatomy and lack underlying diseases specific to stroke; they also face ethical concerns and high cost.

We evaluated the feasibility of performing stroke interventions in the Dundee human cadaveric model. This novel human model inherently incorporates the challenges posed by anatomical variations between individual patients and allows the creation of additional vessel occlusions. Cadavers are prepared using a proprietary method, allowing intracranial vessels to remain open. Using an extracorporeal perfusion pump (Supplementary Figure 1), arterial blood pressure can be modulated. The work complies with ethics regulations and relevant legislation, including the consent of donors in accordance with the Anatomy Act Scotland (1984) and the Human Tissue (Scotland) Act 2006.

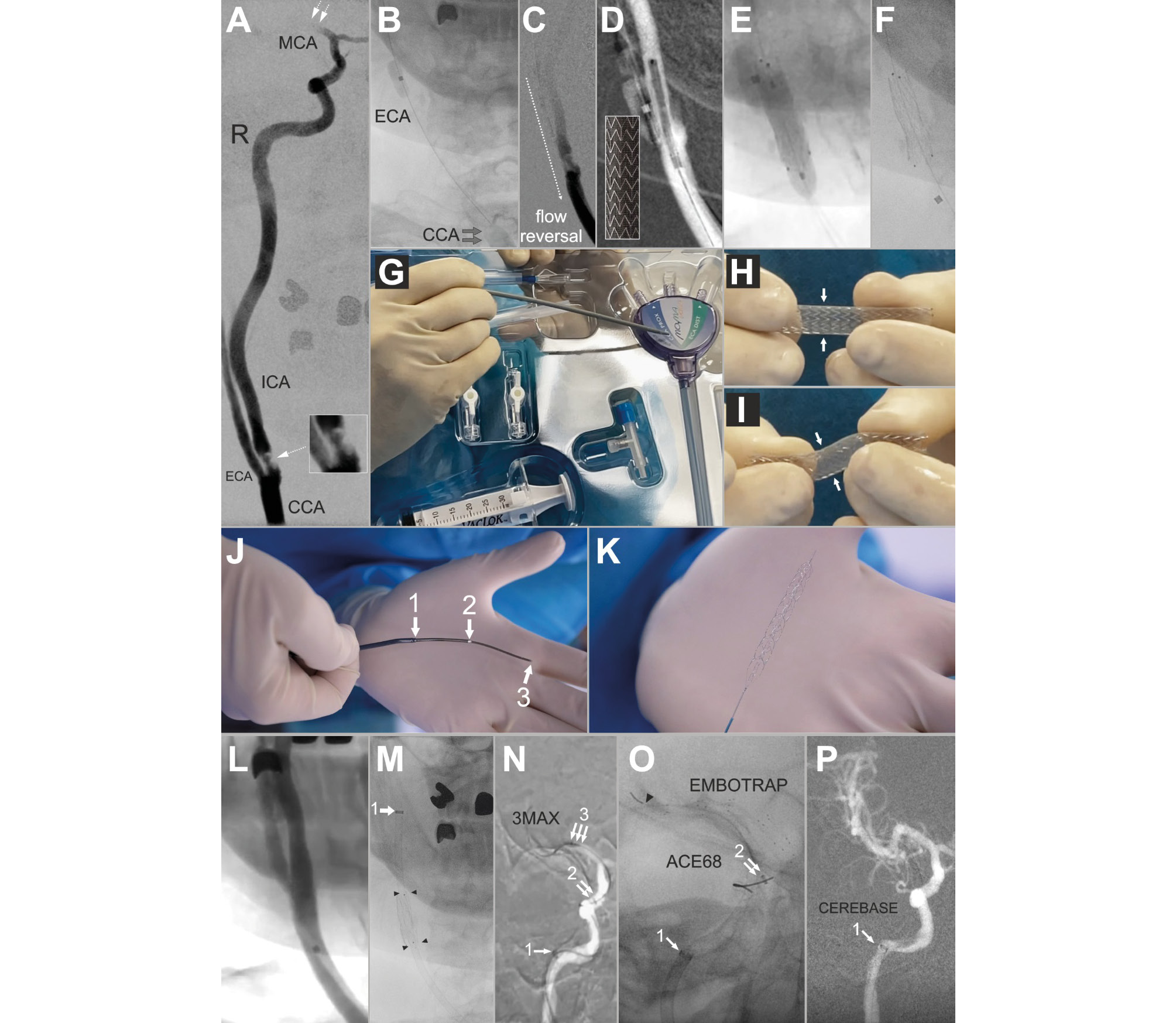

Herein, we report the first ever endovascular treatment of a tandem stroke lesion in a perfused human cadaver (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1, Moving image 1, Moving image 2, Moving image 3, Moving image 4, Moving image 5). The procedure was part of an international operator and team-training workshop, transmitted live via visOR smart glasses (Rods&Cones). It involved devices conventionally used to treat tandem lesions, including aspiration catheters and stentrievers (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 2). Procedural aspects were judged by 5 experienced EST operators involved in the case. The intervention was considered “very realistic” (mean 9.4; scale 0-10: 10 identical to real life, 0 completely different). Online trainees (endovascular operator teams) commented that they would not have realised the case was not being performed in a live human had they not been told afterwards.

Life-like case-based training followed, involving repeated demonstrations of the key procedural steps with interactive discussions (Supplementary Figure 2) and repeated intracranial/extracranial (Moving image 4) stroke interventions.

One fundamental strength of the Dundee human stroke model is the feasibility to perform life-like “emergency” cerebrovascular interventions for which the timing can be electively chosen to fit training logistics. Key procedural steps can be repeated and explained, including procedural strategies and cerebral protection and thrombus extraction strategies (Supplementary Figure 2). Furthermore, team training with life-like scenarios can be performed, including recognition and management of complications. Angiographic imaging necessitates contrast use (Moving image 4), as in live humans. The perfusate is transparent, allowing intravascular imaging. Limitations are similar to those for live humans: vessels can be perforated, and devices – once implanted – stay. This makes the treatment realistic, necessitating – for instance – crossing the carotid stent for repeated intracranial interventions (Figure 1).

In conclusion, we have developed a life-like human cadaveric model for extra- and intracranial stroke interventions. This model allows safe and scheduled skills acquisition for operators and teams, consistent with recent EST training guidelines4. In addition, the model allows medical device familiarisation and evaluation (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1. Key angiographic and procedural images: a live case-like procedure in a female cadaver who died of a tandem stroke aged 78 years (legend in Supplementary data).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID) and Dr Michelle Cooper and Yvonne Rose for their managerial support.

Funding

Funding was provided by an endowment fund from the University of Dundee.

Conflict of interest statement

I.Q. Grunwald is Vice-President of the World Federation for Interventional Stroke Treatment (WIST). P. Musialek has proctored and/or consulted for Abbott, W. L. Gore & Associates, InspireMD, and Medtronic; is Global Co-PI in C-Guardians FDA-IDE trial; serves on the ESC Stroke Council Scientific Documents Task Force; and is the Polish Cardiac Society Board Representative for Stroke and Vascular Interventions Treatment. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Moving image 1. Inflation of the Mo.Ma system proximal balloon and flow reversal for cerebral protection against the ICA lesion (stroke culprit) embolism.

Moving image 2. Primary stenting of the stroke culprit carotid atherosclerotic thromboembolic lesion (antegrade strategy).

Moving image 3. Verification and adjustment of the catheter flush with heparinised saline in a “neuro” set-up.

Moving image 4. Stentriever release that followed an (ineffective) aspiration-only attempt (Figure 1N).

Moving image 5. Digital subtraction angiography showing sluggish flow due to thrombus in the distal ICA.