Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: The prognostic significance of the Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS) criteria during acetylcholine (ACh) provocation testing is uncertain.

Aims: The aim of this study was to assess the prognostic impact of COVADIS criteria in patients with myocardial ischaemia (INOCA) or myocardial infarction (MINOCA) and non-obstructive coronary arteries undergoing ACh provocation testing.

Methods: We enrolled consecutive INOCA and MINOCA patients undergoing ACh provocation testing. The occurrence of each COVADIS criterion was recorded. The primary outcome was the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at follow-up.

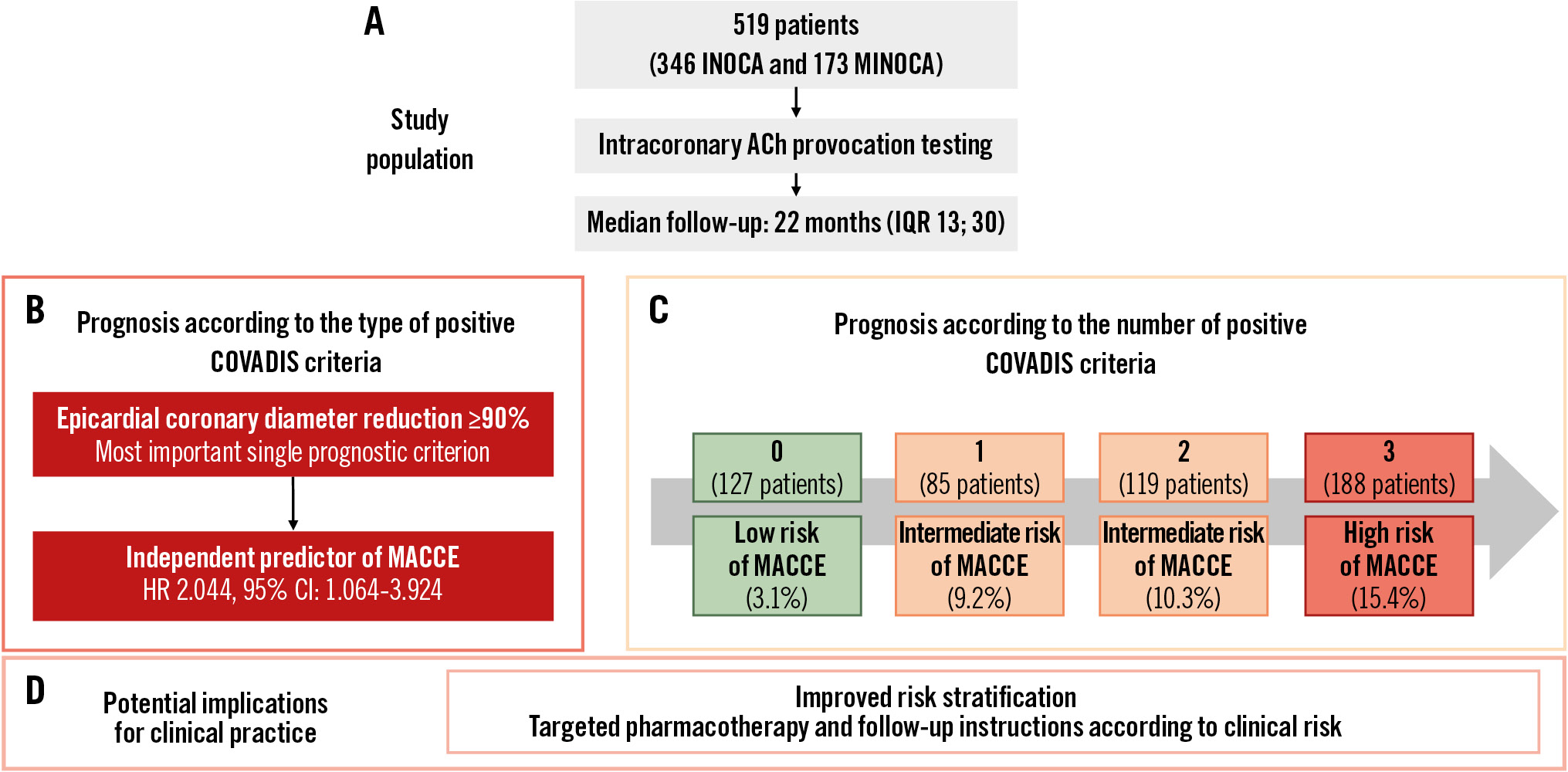

Results: Among 519 patients (346 [66.7%] INOCA and 173 [33.3%] MINOCA), 274 (52.8%) exhibited a positive ACh test. Over a median 22-month follow-up, the highest incidence of MACCE occurred in patients with 3 positive criteria (15.4%), followed by those with 2 (10.3%) and 1 (9.2%), while the lowest incidence occurred in patients with 0 (3.1%; p=0.004). Patients with ≥1 positive criteria had significantly higher MACCE rates than those with 0 (12.5% vs 3.1%; p=0.003). MACCE-free survival differed significantly among the four groups, with the best survival for 0 criteria and the worst for 3 (p=0.004). Epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% and MINOCA were independent MACCE predictors. Among patients with a negative test, an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% was the only independent predictor of MACCE, and the presence of ≥1 criteria in this group was associated with a significantly higher MACCE rate compared to patients without any criteria.

Conclusions: Our findings challenge the binary stratification (positive vs negative) of COVADIS criteria, suggesting an added value of a comprehensive analysis of their components to provide prognostic stratification and personalised treatment.

Ischaemic heart disease remains a leading global health challenge, significantly contributing to morbidity and mortality worldwide1 . Approximately half of the patients undergoing coronary angiography for suspected or confirmed myocardial ischaemia have non-obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD)23. Coronary vasomotor disorders, either at the microvascular or epicardial level, have been demonstrated to be key contributors to myocardial ischaemia in a significant proportion of these patients, with clinical manifestations ranging from ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA) or myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA), to severe clinical presentations like life-threatening arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death456.

Intracoronary provocation testing with administration of acetylcholine (ACh) may elicit epicardial coronary spasm or microvascular spasm in susceptible individuals. This testing can provide valuable insights into coronary vasomotor function and assist in the diagnosis of underlying vasomotor conditions789. The Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS) has established standardised criteria for interpreting the results of such testing1011. Several studies have demonstrated that patients with a positive ACh provocation test are at increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events compared to those with a negative response121314. However, these studies typically classified patients solely based on a positive or negative overall test result, without accounting for the number or types of positive COVADIS criteria observed during the test. Consequently, the prognostic significance of each individual COVADIS criterion remains uncertain, especially regarding whether patients with one or more positive criteria could face an increased CV risk compared to those without any positive components.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prognostic impact of COVADIS criteria in INOCA and MINOCA patients undergoing ACh provocation testing, focusing on the types and number of positive criteria in predicting clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study population

We prospectively enrolled consecutive patients admitted to the Department of Cardiovascular Sciences of Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy, who underwent clinically indicated coronary angiography for suspected myocardial ischaemia or myocardial infarction with angiographic evidence of non-obstructive CAD (angiographically normal coronary arteries or diffuse atherosclerosis with stenosis <50% and/or fractional flow reserve>0.80) and underwent intracoronary provocation testing with ACh from September 2015 to September 2022. We enrolled both patients admitted with suspected INOCA and those with MINOCA diagnosed according to the most recent European Society of Cardiology guidelines1516. Among patients presenting with suspected MINOCA, we excluded those with obvious causes of myocardial infarction (MI) other than suspected coronary vasomotor abnormalities. Clinical, laboratory, echocardiographic and angiographic characteristics of all the included patients were extracted from their electronic medical records by the Gemelli Generator Real World Data Facility. To obtain structural information from unstructured texts (such as clinical diary, radiology reports, etc.), natural language processing algorithms were applied, based on text mining procedures such as sentence/word tokenization, a rule-based approach supported by annotations defined by the clinical subject matter experts, and using semantic/syntactic corrections where necessary17 (Supplementary Appendix 1). The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by our Institutional Review Committee (Comitato Etico Policlinico Gemelli: ID 5405).

Coronary angiography and invasive provocation testing protocol

Coronary angiography was performed using either a radial or femoral artery approach. To fully expose all segments of the coronary arteries, at least two perpendicular projections for the right coronary artery and four projections for the left coronary artery were taken. Intracoronary ACh provocation testing was performed immediately after coronary angiography as previously described1213. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was continuously recorded throughout the test. Coronary angiography was performed 1 minute after each injection and/or when chest pain and/or ischaemic ECG shifts were observed. Coronary angiography and ECG analysis were performed by two expert investigators (R. Rinaldi and M. Russo) who were blinded to the patients’ data. During the test, the patient was clinically monitored and assessed to detect any recognisable ischaemic symptoms, such as chest pain or angina (described as typical retrosternal oppressive chest discomfort or pain). To ensure the accuracy of symptom reporting and to avoid any potential confounding effects, no sedation protocol was employed. The following ECG changes were considered significant and indicative of myocardial ischaemia: (1) horizontal or downsloping ST-segment depression of ≥0.1 mV at 80 milliseconds after the J point in two contiguous leads; (2) ST-segment elevation of ≥0.1 mV in two contiguous leads not including V2-V3, where the thresholds were higher (≥0.2 mV for men aged <40 years, ≥0.25 mV for men aged ≥40 years, and ≥0.15 mV for women); (3) new or deeper T wave inversion in two contiguous leads with prominent R waves18. Test interpretation was performed according to the established COVADIS criteria. Accordingly, a test was considered positive for epicardial coronary spasm when typical ischaemic symptoms (first criterion) and ischaemic ECG changes (second criterion) occurred alongside a ≥90% reduction in the diameter of any epicardial coronary artery segment compared to baseline (third criterion)10. Conversely, a test was considered positive for coronary microvascular spasm when the first and second criteria were accompanied by <90% diameter reduction (third criterion)11. Additionally, the individual occurrence of each COVADIS criterion was collected for every patient, in particular (1) the presence of typical ischaemic symptoms, (2) ischaemic ECG changes, and (3) epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90%. The interobserver Kappa and intraobserver coefficients for the diagnosis of epicardial coronary constriction (>90%) and positive ischaemic ECG changes were 0.91 and 0.92, respectively. In the case of any discordance between the two investigators, a consensus was obtained with the opinion of a third investigator (R.A. Montone).

Study endpoints

All patients received clinical follow-up by telephonic interviews and/or clinical visits at 6, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months. The primary endpoint was the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE). MACCE were defined as the composite of CV death, non-fatal MI, hospitalisation due to unstable angina (UA), and stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA)1819. We only counted the number of patients whose first occurrence of MACCE was during the follow-up period. We also recorded the recurrence of angina episodes (whether or not they required hospitalisation) during the follow-up period, and we collected the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) summary score at 12 months20 (Supplementary Appendix 1).

Statistical analysis

Data distribution for continuous variables was assessed according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or as median and interquartile range (IQR) according to normal or non-normal distribution of the variable, respectively. Continuous variables were compared among multiple groups using a one-way analysis of variance test or the Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Categorical data were evaluated using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Univariable Cox regression analysis was applied to assess the relationship between individual variables and MACCE. Multivariable Cox regression was then applied to identify those variables that were independently associated with MACCE. To this aim, we included in the multivariable model only variables showing a p-value≤0.05 at univariable analysis. Cox regression analysis was also performed in the ACh-negative population to assess the potential prognostic impact of microvascular spasm. Survival curves of MACCE according to the type of ACh test response (positive or negative) and the number of positive COVADIS criteria observed during the test are shown using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared by using the log-rank test. A two-tailed analysis was performed, and a p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 21 (IBM).

Results

Baseline characteristics of study population

We enrolled 519 patients (mean age 61.4±12.1 years; 275 [53.0%] females) with myocardial ischaemia and non-obstructed coronary arteries undergoing ACh provocation testing. Among them, 346 (66.7%) presented with INOCA and 173 (33.3%) with MINOCA. A positive ACh test according to the COVADIS criteria was observed in 274 patients (52.8%), with 188 (68.6%) developing epicardial spasm and 86 (31.4%) microvascular spasm. Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical, ECG, echocardiographic and angiographic features in the overall population and according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria observed during ACh provocation testing.

| Characteristics | Overall population (n=519) | 0 COVADIS components (n=127) | 1 COVADIS component (n=85) | 2 COVADIS components (n=119) | 3 COVADIS components (n=188) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Age, years | 61.4±12.1 | 60.1±11.7 | 62.3±11.8 | 60.7±12.5 | 62.4±12.2 | 0.297 |

| Male sex | 275 (53.0) | 59 (46.5) | 47 (55.3) | 87 (73.1) | 82 (43.6) | <0.001* |

| Hypertension | 333 (64.2) | 77 (60.6) | 55 (64.7) | 83 (69.7) | 118 (62.8) | 0.480 |

| Diabetes | 93 (17.9) | 17 (13.4) | 18 (21.2) | 18 (15.1) | 40 (21.3) | 0.216 |

| Smoking | 147 (28.3) | 32 (25.2) | 25 (29.4) | 33 (27.7) | 57 (30.3) | 0.789 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 279 (53.8) | 74 (58.3) | 47 (55.3) | 67 (56.3) | 91 (48.4) | 0.308 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 46 (8.9) | 11 (8.7) | 7 (8.2) | 7 (5.9) | 21 (11.2) | 0.458 |

| Family history of CAD | 174 (33.5) | 48 (37.8) | 29 (34.1) | 43 (36.1) | 54 (28.7) | 0.339 |

| Clinical presentation | 0.168 | |||||

| MINOCA | 173 (33.3) | 35 (27.6) | 25 (29.4) | 40 (33.6) | 73 (38.8) | |

| INOCA | 346 (66.7) | 92 (72.4) | 60 (70.6) | 79 (66.4) | 115 (61.2) | |

| Previous CV history | 100 (19.3) | 30 (23.6) | 16 (18.8) | 17 (14.3) | 37 (19.7) | 0.324 |

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| Hb, g/dL | 13.4±1.4 | 13.5±1.4 | 13.6±1.5 | 13.2±1.4 | 13.5±1.4 | 0.147 |

| WBC, x103/L | 7.3±2.1 | 7.1±1.8 | 7.4±1.9 | 7.7±2.3 | 7.2±2.2 | 0.140 |

| Serum creatinine on admission, mg/dL | 0.83 [0.71; 0.97] | 0.82 [0.72; 0.98] | 0.80 [0.68; 0.95] | 0.82 [0.72; 0.95] | 0.84 [0.70; 0.99] | 0.380 |

| hs-cTnI at admission, ng/mL | 0.2 [0.01; 4.00] | 0.9 [0.01; 6.0] | 0.4 [0.01; 4.7] | 0.1 [0.01; 3.0] | 0.1 [0.01; 3.7] | 0.172 |

| CRP, mg/L | 0.5 [0.1; 2.6] | 0.5 [0.1; 2.7] | 0.5 [0.1; 2.6] | 0.5 [0.1; 2.9] | 0.05 [0.05; 2.4] | 0.418 |

| Echocardiographic data | ||||||

| LVEF on admission, % | 59.5±5.8 | 59.7±5.4 | 59.6±5.2 | 60.1±5.8 | 59.0±6.2 | 0.415 |

| Diastolic dysfunction | 254 (48.9) | 58 (45.7) | 37 (43.5) | 64 (53.8) | 95 (50.5) | 0.416 |

| Angiographic data | ||||||

| Presence of non-obstructive CAD | 259 (49.9) | 63 (49.6) | 41 (48.2) | 58 (48.7) | 97 (51.6) | 0.945 |

| Provocation test | ||||||

| Positive | 274 (52.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 86 (72.3) | 188 (100) | <0.001* |

| Type of positive response | <0.001* | |||||

| Epicardial spasm | 188 (68.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 188 (100) | |

| Microvascular spasm | 86 (31.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 86 (72.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Reproduction of typical anginal symptoms | 330 (63.6) | 0 (0) | 33 (38.8) | 109 (91.6) | 188 (100) | <0.001* |

| Reproduction of ischaemic ECG changes | 313 (60.3) | 0 (0) | 19 (22.4) | 106 (89.1) | 188 (100) | <0.001* |

| Epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% | 244 (47.0) | 0 (0) | 33 (38.8) | 23 (19.3) | 188 (100) | <0.001* |

| Epicardial coronary diameter reduction <90% | 99 (19.1) | 14 (11.0) | 4 (4.7) | 81 (68.1) | 0 (0) | <0.001* |

| Highest ACh dose (≥100 mcg) | 323 (62.2) | 89 (70.1) | 58 (68.2) | 75 (63.0) | 101 (53.7) | 0.015* |

| ACh dose 200 mcg | 10 (1.9) | 2 (1.6) | 4 (4.7) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0.227 |

| ACh maximum dose | 100 [50; 100] | 100 [50; 100] | 100 [50; 100] | 100 [50; 100] | 100 [50; 100] | 0.698 |

| Therapy at discharge | ||||||

| Aspirin | 256 (49.3) | 62 (48.8) | 40 (47.1) | 51 (42.9) | 103 (54.8) | 0.219 |

| Clopidogrel | 56 (10.8) | 20 (15.7) | 6 (7.1) | 12 (10.1) | 18 (9.6) | 0.185 |

| Ticagrelor | 5 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.6) | 0.643 |

| Prasugrel | 4 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.508 |

| Beta blockers | 178 (34.3) | 65 (51.2) | 31 (36.5) | 33 (27.7) | 49 (26.1) | <0.001* |

| CCBs | 343 (66.1) | 36 (28.3) | 42 (49.4) | 89 (74.8) | 176 (93.6) | <0.001* |

| ACEi/ARBs | 341 (65.7) | 83 (65.4) | 52 (61.2) | 84 (70.6) | 122 (64.9) | 0.553 |

| Statins | 358 (69.0) | 79 (62.2) | 49 (57.6) | 91 (76.5) | 139 (73.9) | 0.004* |

| Diuretics | 76 (14.6) | 19 (15.0) | 10 (11.8) | 18 (15.1) | 29 (15.4) | 0.876 |

| Nitrates | 14 (2.7) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (2.5) | 8 (4.3) | 0.314 |

| NOACs | 47 (9.1) | 9 (7.1) | 9 (10.6) | 10 (8.5) | 19 (10.1) | 0.768 |

| Values are expressed as median [IQR], n (%), or mean±SD. *Indicates statistical significance. ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACh: acetylcholine; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCB: calcium channel blocker; COVADIS: Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group; CRP: C-reactive protein; CV: cardiovascular; ECG: electrocardiogram; Hb: haemoglobin; hs-cTnI: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; INOCA: ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries; IQR: interquartile range; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MINOCA: myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries; NOAC: novel oral anticoagulant; SD: standard deviation; WBC: white blood cell count | ||||||

Clinical outcomes according to ACh provocation testing response

Over a median follow-up of 22 months (IQR 13; 30), MACCE occurred in 53 (10.2%) patients. The incidence of MACCE was higher in patients with a positive ACh test than in those with a negative ACh test (36 [13.1%] vs 17 [6.9%]; p=0.009), mainly driven by a higher rate of hospitalisations for UA (26 [9.5%] vs 13 [5.3%]; p=0.029). Patients with a positive ACh test also had a higher rate of recurrent angina and a lower SAQ summary score at 12-month follow-up than those with a negative result (103 [37.6%] vs 50 [20.4%]; p<0.001; and 82 [IQR 73; 90] vs 88 [IQR 78; 100]; p<0.001, respectively) (Supplementary Table 1). Kaplan-Meier curves revealed that patients with a positive ACh test had a significantly lower MACCE-free survival compared to those with a negative one (p=0.009) (Supplementary Figure 1). Among patients who met all three criteria for epicardial spasm (n=188), MACCE occurred in 29 (15.4%) patients, while in those with microvascular spasm (n=86), characterised by ischaemic ECG changes and typical ischaemic symptoms without epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90%, MACCE occurred in 7 (8.1%) patients (p=0.108).

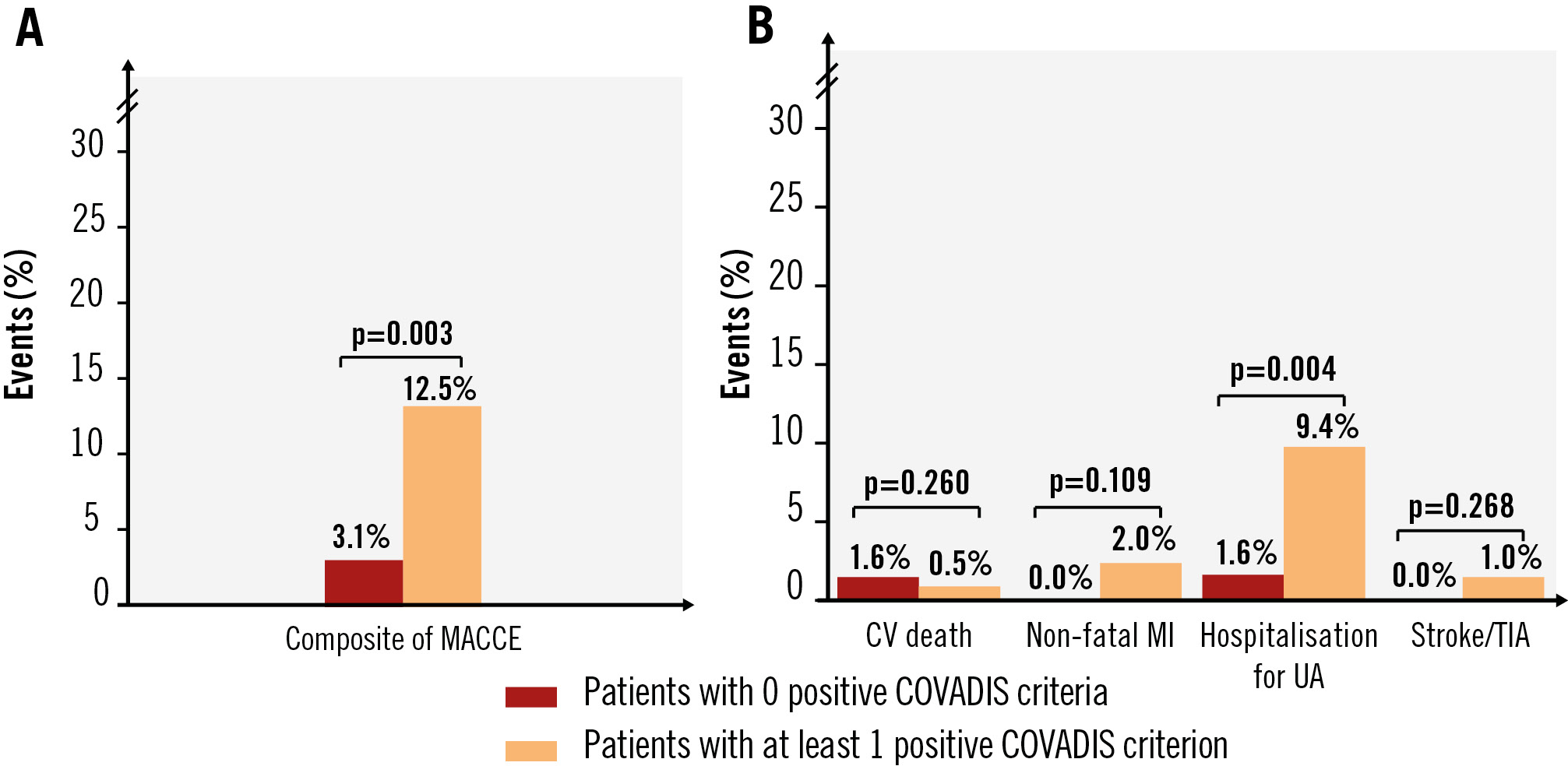

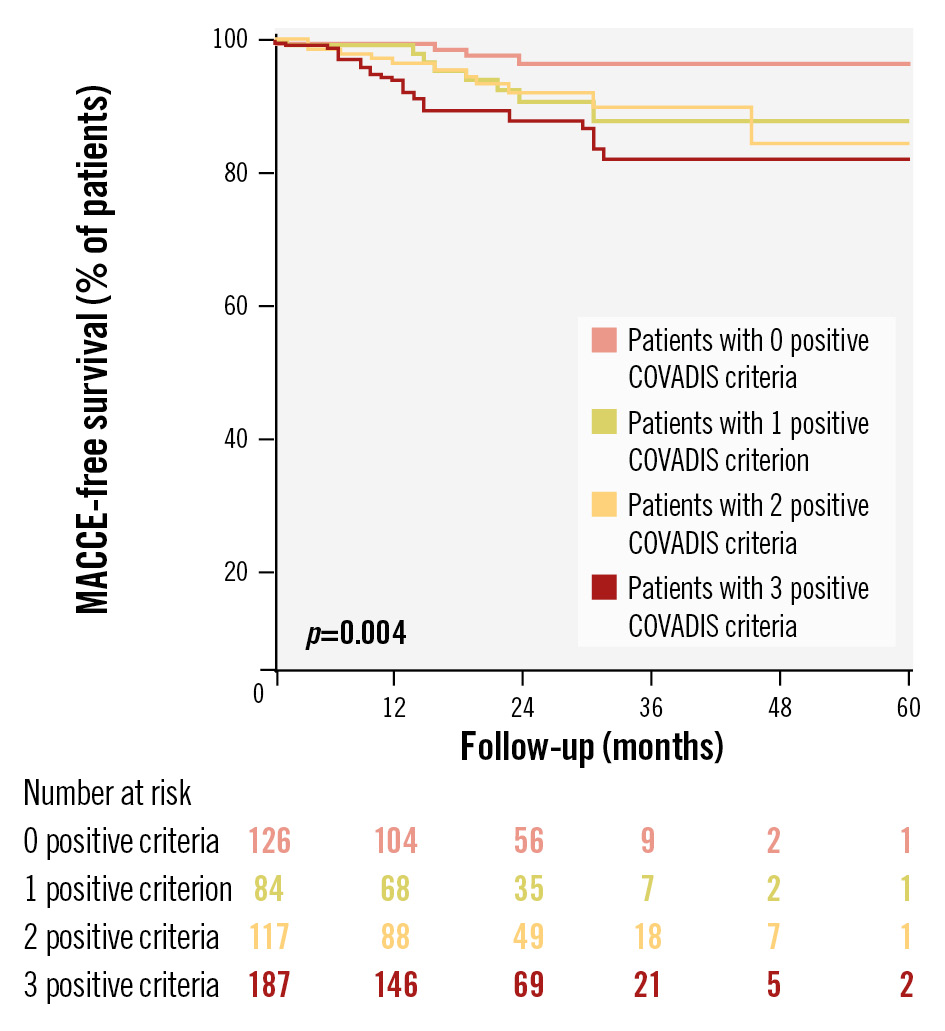

Clinical outcomes according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria in the overall population

The incidence of MACCE increased with the number of positive COVADIS criteria: 15.4% in patients with 3 criteria, 10.3% with 2, and 9.2% with 1, compared to 3.1% in those with 0 criteria (p=0.004). Similarly, the incidence of recurrent angina increased with the number of positive COVADIS criteria (p=0.004), while the SAQ summary score at 12-month follow-up was lower with increasing positive criteria (p=0.037) (Table 2). The incidence of MACCE was significantly higher among patients with at least 1 positive COVADIS criterion compared to those with 0 (12.5% vs 3.1%; p=0.003), mainly driven by a higher prevalence of hospitalisation for UA (p=0.004) (Figure 1). Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed worse MACCE-free survival with an increasing number of positive criteria (p=0.004) (Figure 2).

Table 2. Clinical outcome in the overall population and according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria observed during acetylcholine provocation testing.

| Characteristics | Overall population (n=519) | 0 COVADIS criteria (n=127) | 1 COVADIS criteria (n=87) | 2 COVADIS criteria (n=117) | 3 COVADIS criteria (n=188) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE | 53 (10.2) | 4 (3.1) | 8 (9.2) | 12 (10.3) | 29 (15.4) | 0.004* |

| CV death | 4 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 0.429 |

| Non-fatal MI | 8 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (3.4) | 3 (1.6) | 0.265 |

| Hospitalisation for UA | 39 (7.5) | 2 (1.6) | 6 (6.9) | 9 (7.7) | 22 (11.7) | 0.007* |

| Stroke/TIA | 4 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.1) | 0.670 |

| Recurrent angina | 153 (29.5) | 24 (18.9) | 19 (21.8) | 41 (35.0) | 69 (36.7) | 0.004* |

| SAQ summary score | 84 [75;100] | 88 [76; 100] | 86 [78; 100] | 84 [74; 90] | 82 [72; 92] | 0.037* |

| Follow-up time, months | 22 [13; 30] | 22 [13; 30] | 23 [13; 31] | 22 [12; 30] | 21 [13; 30] | 0.997 |

| Values are expressed as n (%) or median [IQR]. *Indicates statistical significance. COVADIS: Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group; CV: cardiovascular; IQR: interquartile range; MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; SAQ: Seattle Angina Questionnaire; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; UA: unstable angina | ||||||

Figure 1. Incidence of MACCE at follow-up according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria observed during ACh provocation testing. A) Incidence of the composite MACCE; (B) incidence of the individual MACCE components. ACh: acetylcholine; COVADIS: Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group; CV: cardiovascular; MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; UA: unstable angina

Figure 2. Survival Kaplan-Meier curves for MACCE according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria observed during ACh provocation testing. ACh: acetylcholine; COVADIS: Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group; MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

Predictors of MACCE in the overall population

At multivariable Cox regression analysis, epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% (hazard ratio [HR] 2.044, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.064-3.924; p=0.032) and MINOCA as the clinical presentation (HR 1.892, 95% CI: 1.093-3.275; p=0.023) were the only independent predictors for the occurrence of MACCE in the overall population (Table 3). When considered as an ordinal variable in multivariable Cox regression analysis, the number of positive COVADIS criteria proportionally increased the risk of MACCE (HR 1.560 per criterion, 95% CI: 1.180-2.062; p=0.002). The interaction for a possible influence of clinical presentation (INOCA vs MINOCA) on these results was not significant (p for interaction for an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% and INOCA/MINOCA for MACCE=0.100; p for interaction for the number of positive criteria observed during ACh test and INOCA/MINOCA for MACCE=0.055).

Table 3. Predictors of MACCE in the overall population by univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis.

| Predictors of MACCE | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Typical anginal symptoms during ACh provocation testing | 2.199 (1.129-4.281) | 0.020* | 0.921 (0.415-2.644) | 0.921 |

| Ischaemic ECG changes during ACh provocation testing | 2.270 (1.191-4.330) | 0.013* | 1.165 (0.474-2.861) | 0.739 |

| Epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% | 2.775 (1.539-5.004) | 0.001* | 2.044 (1.064-3.924) | 0.032* |

| MINOCA as clinical presentation | 1.951 (1.132-3.363) | 0.016* | 1.892 (1.093-3.275) | 0.023* |

| Beta blocker therapy at discharge | 0.492 (0.253-0.958) | 0.037* | 0.601 (0.306-1.179) | 0.139 |

| CCB therapy at discharge | 2.585 (1.260-5.304) | 0.010* | 1.617 (0.700-3.735) | 0.261 |

| *Indicates statistical significance. All the characteristics shown in Table 1 were tested to predict MACCE at follow-up, although only variables with a p-value<0.05 have been shown in this table. Variables that were significantly (p<0.05) related to MACCE at follow-up on univariable Cox regression analysis were included in the multivariable Cox regression analysis. ACh: acetylcholine; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CI: confidence interval; ECG: electrocardiogram; HR: hazard ratio; MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MINOCA: myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries | ||||

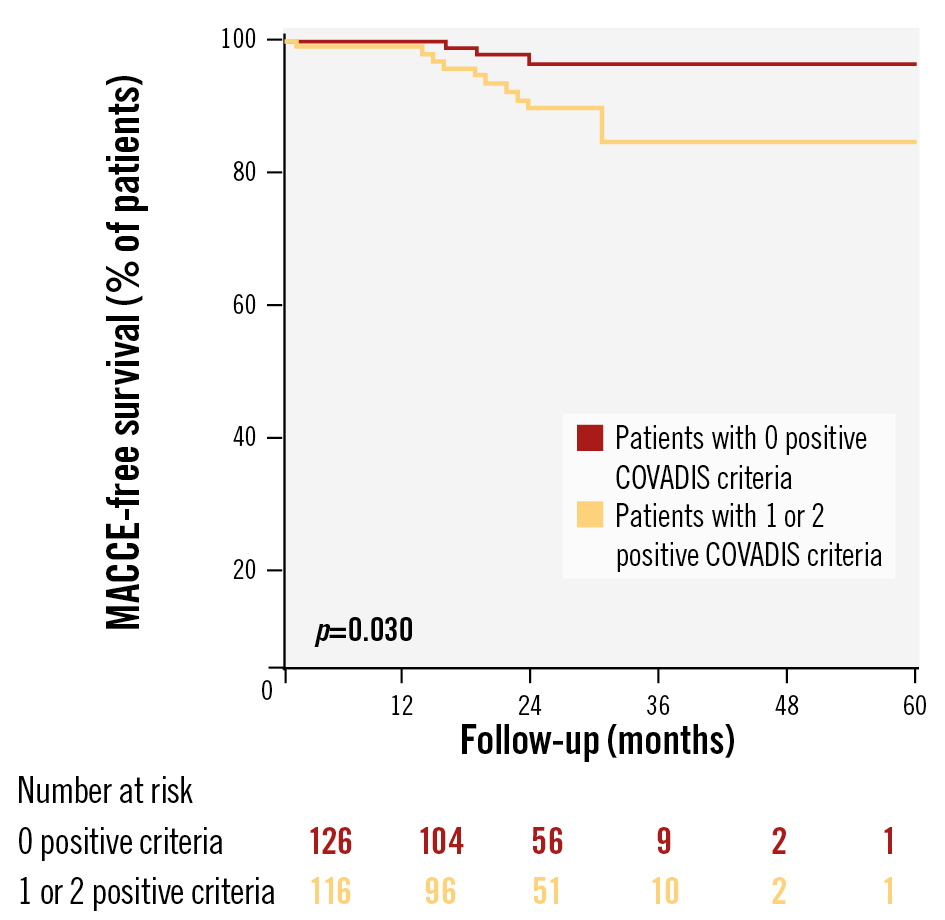

Clinical outcomes according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria in the ACh-negative population

Among the 245 patients with a negative ACh test response, an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% (HR 3.132, 95% CI: 1.163-8.433; p=0.024) was the only independent predictor for the occurrence of MACCE at multivariable Cox regression analysis (Table 4). Kaplan-Meier curves showed lower MACCE-free survival in patients with at least 1 positive COVADIS criterion compared to those with 0 (p=0.030) (Figure 3).

Table 4. Predictors of MACCE in the ACh-negative population by univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis.

| Predictors of MACCE | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% | 3.208 (1.192-8.629) | 0.021* | 3.132 (1.163-8.433) | 0.024* |

| Dyslipidaemia | 0.342 (0.119-0.984) | 0.047* | 0.350 (0.121-1.007) | 0.052 |

| *Indicates statistical significance. All the characteristics shown in Table 1 were tested to predict MACCE at follow-up, although only variables with a p-value<0.05 have been shown in this table. Variables that were significantly (p<0.05) related to MACCE at follow-up on univariable Cox regression analysis were included in the multivariable Cox regression analysis. ACh: acetylcholine; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events | ||||

Figure 3. Survival Kaplan-Meier curves for MACCE in the ACh-negative population according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria observed during ACh provocation testing. ACh: acetylcholine; COVADIS: Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group; MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

Clinical outcomes according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria in patients with or without epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90%

Among the 244 patients with an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90%, no significant differences in MACCE or recurrent angina were observed between those meeting different types and numbers of COVADIS criteria (allp>0.05). The SAQ summary score at 12-month follow-up was the lowest in patients meeting all 3 COVADIS criteria and the highest in those with an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% and typical ischaemic symptoms without ischaemic ECG changes (82 [IQR 72; 92], 90 [IQR 84; 100], respectively; overall p=0.044) (Supplementary Table 2).

Among the 275 patients without an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90%, no significant differences in MACCE were observed according to the number of positive COVADIS criteria (p=0.259). The highest rate of recurrent angina occurred in patients with 2 positive COVADIS criteria (37.5%), while the lowest incidence was found in those with 0 positive criteria (18.9%; p=0.029). The SAQ summary score at 12-month follow-up was the lowest in patients with 2 positive COVADIS criteria and the highest in those with 0 positive COVADIS criteria (84 [IQR 74; 90], 88 [IQR 76; 100], respectively; p=0.033) (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the most extensive analysis of the prognostic significance of COVADIS criteria in INOCA and MINOCA patients who underwent intracoronary provocation testing with ACh.

The main results of our study can be summarised as follows: (1) the overall incidence of MACCE in patients with one or more positive COVADIS criteria is not negligible (12.5%) and is higher than in those without any positive COVADIS criteria (3.1%), primarily driven by rehospitalisations for UA; (2) MACCE-free survival is proportionally lower with an increasing number of positive COVADIS criteria, with the best clinical outcome for patients with 0 positive COVADIS criteria and the worst for those with all 3 criteria; (3) among COVADIS criteria, an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% represents the most important prognostic criterion; (4) MINOCA as the clinical presentation and an epicardial coronary diameter reduction during ACh provocation testing are the only independent predictors of MACCE at follow-up; (5) among patients with a negative ACh test, an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% is the only independent predictor of MACCE at follow-up, and the presence of at least one positive COVADIS criterion is significantly associated with reduced MACCE-free survival compared to those without any positive criteria.

Current literature emphasises the prognostic significance of ACh provocation testing in INOCA and MINOCA patients, associating a positive result with an increased risk of CV events compared to a negative result121314212223. The test’s interpretation traditionally follows the established COVADIS criteria, where the occurrence of only one criterion, or two criteria not including the first and second, is classified as a negative or inconclusive result1011. Our study introduced new insights into the prognostic impact of any positive criteria from ACh provocation testing. Indeed, we observed that patients without any positive criteria had a lower risk of CV events (3.1%), while those with at least one positive criterion faced a notably higher risk (12.5%). Furthermore, a clinical presentation of MINOCA and an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90% were the only independent predictors of MACCE at follow-up, with the number of COVADIS criteria correlating with a proportionally higher incidence of clinical events. These findings suggest that relying solely on a binary classification of positive or negative results may not accurately capture individual risk profiles. While the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated, several explanations may justify our findings. MINOCA typically implies more aggressive functional alterations underlying myocardial ischaemia compared to INOCA242526. Long-term studies have shown that MINOCA is associated with a substantial risk of death and CV events27282930. Similarly, significant epicardial vasoconstriction (i.e., ≥90%) observed during ACh testing, even without symptoms or ECG changes, may indicate severe underlying coronary vasomotor dysfunction with important prognostic implications. This dysfunction may be driven by factors such as endothelial dysfunction, characterised by an imbalance between vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive agents (e.g., nitric oxide and endothelin-1), abnormal hyperreactivity of vascular smooth muscle cells and inflammatory processes within the coronary vasculature3132. Collectively, these alterations may predispose individuals to frequent and severe ischaemic episodes, increasing their risk of CV events33. However, these mechanisms remain speculative and require further investigation.

Interestingly, we also found that significant epicardial vasoconstriction was the only independent predictor of MACCE even in patients with a negative ACh test. This suggests that such vasoconstriction, even in isolation and without evidence of ischaemia, may still carry substantial prognostic weight. Additionally, the association between any positive COVADIS criteria and reduced MACCE-free survival in this subgroup highlights that each criterion within the COVADIS framework may offer valuable prognostic information, regardless of the overall test result. Specifically, both the number of positive COVADIS criteria and the occurrence of an epicardial coronary diameter reduction of ≥90% could be key elements for risk stratification. Among the COVADIS criteria, an epicardial coronary diameter reduction of ≥90%, even when occurring alone, emerged as a robust and independent predictor of adverse CV outcomes. Moreover, the accumulation of positive criteria increased the likelihood of clinical events at follow-up, and, even in the absence of significant epicardial constriction, multiple positive criteria were associated with an increased incidence of recurrent angina and lower 12-month SAQ summary scores. Lower SAQ scores were observed in patients with 3 positive COVADIS criteria, despite being prescribed calcium channel blockers (CCBs) more frequently and beta blockers less often, reflecting adherence to current clinical guidelines15 but suggesting that symptom control remains challenging in this group. In the current era of precision medicine, where patient care is increasingly tailored to individual risk profiles, these findings underscore the potential value of a detailed analysis of each component of the ACh provocation test, including both the type and number of positive COVADIS criteria, for precise risk stratification and management (Central illustration). A more comprehensive assessment, beyond a binary positive or negative categorisation, could improve the identification of patients at higher CV risk, enabling more targeted follow-up and therapeutic intervention. Potential strategies might include lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and dietary improvements, along with enhanced pharmacological management3435. For patients with specific COVADIS criteria, such as significant epicardial constriction, targeted pharmacotherapy − including CCBs or long-acting nitrates for vasospasm, as well as statins or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for endothelial dysfunction − could be beneficial363738. Nevertheless, shifting the paradigm in the approach to patients undergoing ACh provocation testing holds the potential to enhance clinical outcomes by enabling treatment strategies that are more closely aligned with each patient’s unique response to the test.

Central illustration. Prognostic significance of individual COVADIS criteria in patients undergoing acetylcholine provocation testing. A) Study population. Prognosis according to the type (B) and number (C) of positive COVADIS criteria. D) Potential implications. ACh: acetylcholine; CI: confidence interval; COVADIS: Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group; HR: hazard ratio; INOCA: ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries; IQR: interquartile range; MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MINOCA: myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries

Limitations

Some limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, this was a single-centre study with a relatively small sample size, limiting the generalisability of our findings to broader patient populations. Furthermore, the observational design of our study only allows for identifying associations, not establishing causality. Second, coronary blood flow and coronary flow reserve and resistance were not measured during the invasive study; thus, their potential relationship with the response to vasoconstrictor stimuli remains undetermined. Third, in MINOCA patients taking vasoactive drugs, the provocation testing was not performed after a washout period for CCBs and nitrates, potentially interfering with the result of the test. Fourth, the choice to perform a provocation test, especially in patients presenting with stable angina, was left to the operator’s discretion. This could have resulted in a selection bias and may explain the higher prevalence of MINOCA in our study population compared with previous studies. Furthermore, the choice to administer the maximal ACh dose (200 mcg) was also left to the operator’s discretion, and in the ACh-negative group, 125 out of 127 patients did not receive the maximum dose, which could have introduced false negatives. Fifth, by definition, a diagnosis of microvascular spasm does not include an epicardial coronary diameter reduction ≥90%, which is a key indicator of epicardial spasm. However, it does require the presence of the two other COVADIS criteria: typical anginal symptoms and ischaemic ECG changes. This diagnostic framework means that evaluating the impact of “the number of positive criteria” beyond the two mandatories for diagnosing microvascular spasm was not feasible. In this specific population, the utility of counting multiple positive criteria to predict risk is inherently limited by the diagnostic criteria for microvascular spasm itself. This underscores the need for developing additional or alternative criteria for better risk stratification of patients diagnosed with microvascular spasm. Finally, the differences in MACCE rates between the subgroups were largely influenced by admissions for UA. Since the admitting providers were not blinded to the ACh test outcomes, this could have affected their clinical decision-making regarding chest pain management. Indeed, this awareness might have led to a higher likelihood of admitting patients who had positive coronary spasm tests. Additionally, detailed data on diagnostic and therapeutic interventions following hospital admissions for UA were not collected. Therefore, it is important to interpret our results with caution. Future studies, ideally involving larger cohorts and blinded designs, are necessary to validate our findings, explore the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms linking COVADIS criteria positivity with worse clinical outcomes, and evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed therapeutic approaches.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study contributes to the growing understanding of the prognostic value of ACh provocation testing in patients with INOCA and MINOCA. We demonstrated that both the type (e.g., significant epicardial vasoconstriction) and the number of positive COVADIS criteria hold important clinical implications for patient risk stratification and management. These findings reinforce the importance of a detailed analysis of vasomotor test results and a personalised approach to treatment, which may ultimately lead to improved clinical outcomes for this patient population. Future research should focus on integrating these findings into clinical practice, exploring the pathophysiology underlying these associations, and developing tailored therapeutic interventions to mitigate risk in this vulnerable group of patients.

Impact on daily practice

This study points out the necessity of advancing beyond binary outcomes in acetylcholine (ACh) provocation testing to enhance patient care. The findings suggest that integrating a detailed analysis of individual Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS) criteria into clinical assessments can more accurately stratify cardiovascular risk. Clinicians should consider incorporating this personalised approach into their diagnostic and management strategies for patients with coronary vasomotor disorders, potentially leading to more personalised and effective treatment plans. Future research should focus on validating these findings in larger, multicentre studies and exploring the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms that link specific COVADIS criteria with cardiovascular outcomes. Additionally, developing targeted therapeutic interventions based on the comprehensive evaluation of ACh provocation test results could further refine risk stratification and management strategies for patients with coronary vasomotor disorders, moving closer to the goal of precision medicine in cardiovascular care.

Conflict of interest statement

F. Burzotta received speaker fees from Medtronic, Abiomed, Abbott, and Terumo. F. Crea received speaker fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Menarini, Chiesi, and Daiichi Sankyo. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.