Abstract

The optimal antithrombotic management of atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who require oral anticoagulation (OAC) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains unclear. Current guidelines recommend dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT; OAC plus P2Y12 inhibitor – preferably clopidogrel) after a short course of triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT; DAT plus aspirin). Although DAT reduces bleeding risk compared to TAT, this is counterbalanced by an increase in ischaemic events. Aspirin provides early ischaemic benefit, but TAT is associated with an increased haemorrhagic burden; therefore, we propose a 30-day dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT; aspirin plus P2Y12 inhibitor) strategy post-PCI, temporarily omitting OAC. The study aims to compare bleeding and ischaemic risk between a 30-day DAPT strategy following PCI and a guideline-directed therapy in AF patients requiring OAC. WOEST-3 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04436978) is an investigator-initiated, international, open-label, randomised controlled trial (RCT). AF patients requiring OAC who have undergone successful PCI will be randomised within 72 hours after PCI to guideline-directed therapy (edoxaban plus P2Y12 inhibitor plus limited duration of aspirin) or a 30-day DAPT strategy (P2Y12 inhibitor plus aspirin, immediately discontinuing OAC) followed by DAT (edoxaban plus P2Y12 inhibitor). With a sample size of 2,000 patients, this trial is powered to assess both superiority for major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding and non-inferiority for a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stroke, systemic embolism or stent thrombosis. In summary, the WOEST-3 trial is the first RCT temporarily omitting OAC in AF patients, comparing a 30-day DAPT strategy with guideline-directed therapy post-PCI to reduce bleeding events without hampering efficacy.

In patients with concomitant atrial fibrillation (AF) and coronary artery disease (CAD), it is crucial to achieve an optimal balance between the ischaemic risk associated with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the cardioembolic risk associated with AF, and the haemorrhagic risk imposed by antithrombotic therapy12. AF, the most common cardiac arrhythmia worldwide, currently affects >10 million patients in Europe, and its prevalence continues to rise34. Given their shared risk factors, it often coexists with CAD5. Approximately 1 in 5 patients with AF undergo PCI, whereas 1 in 10 patients hospitalised with ACS or undergoing PCI develop new-onset AF6.

To prevent ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism, most AF patients require long-term oral anticoagulant (OAC) treatment3. In patients presenting with ACS or undergoing PCI, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT; P2Y12inhibitor plus aspirin) is the cornerstone to prevent coronary ischaemic events, i.e., stent thrombosis (ST) and myocardial infarction (MI)7. For both cardioembolic and coronary ischaemic event protection, patients with AF undergoing PCI thus have a theoretical need for a combination of OAC and antiplatelet therapy37. Triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT; OAC plus DAPT) has, therefore, been the default strategy for years. However, long-term TAT has a detrimental effect on haemorrhagic risk, whilst bleeding (especially major) is associated with mortality89. Several dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT; OAC plus P2Y12 inhibitor) regimens have demonstrated that vitamin K antagonist (VKA) or non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) plus P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel was used in >90% of patients), omitting aspirin, reduced bleeding complications compared to conventional TAT1011121314. Current international guidelines and consensus statements therefore recommend the use of a NOAC, instead of VKA, in combination with single antiplatelet therapy, preferably clopidogrel, and to limit the use of aspirin to ≤1 week, or ≤30 days in high ischaemic risk patients71516. However, this reduction in bleeding complications has been counterbalanced by an increase in coronary ischaemic events (ST risk ratio [RR] 1.54, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.10-2.14; MI RR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.04-1.46)17.

Given that coronary ischaemic risk peaks within the first month post-PCI, there is ongoing debate regarding the utilisation of aspirin during this critical period1218. While aspirin seems to provide early ischaemic benefit, but given that TAT is associated with more bleeding, the WOEST-3 trial proposes a 30-day DAPT strategy post-PCI, temporarily omitting OAC, instead of guideline-directed TAT followed by DAT. The temporary omission of OAC not only aims to further decrease bleeding risk but also ensures optimal coronary protection against ischaemic events during the early post-PCI period.

Methods

What is the Optimal Antithrombotic Strategy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Having Acute Coronary Syndrome or Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention? (WOEST-3, ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04436978) is an investigator-initiated, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the bleeding risk (i.e., safety) and ischaemic risk (i.e., efficacy) of a 30-day DAPT strategy post-PCI versus guideline-directed therapy in AF patients who require OAC after undergoing successful PCI.

A total of 2,000 patients will be enrolled. Enrolment started in January 2023 and is expected to conclude in 2026. Currently, over 300 patients have been randomised. An overview of the participating clinical sites is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1.

This trial is being conducted in compliance with the study protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki, and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, as defined by the International Council on Harmonisation. Medical ethics committee approval is required at all participating sites prior to study initiation. A yearly progress and safety report will be submitted to the accredited medical research ethics committees of the concerned member states. Patient identification codes and randomisation numbers are in place to maintain patient confidentiality. Eligible patients will be informed, both orally and in writing, on the possible risks and benefits of trial participation as well as their rights and duties. Prior to randomisation, eligible patients must provide written informed consent. Patient data are entered into an electronic case report form.

STUDY POPULATION

Patients are eligible for inclusion if they are ≥18 years old, have undergone successful PCI, and have a history of or newly diagnosed AF or atrial flutter with a long-term (≥1 year) indication for OAC. Exclusion criteria include recent ischaemic stroke, history of haemorrhagic stroke, an indication for OAC other than AF or atrial flutter, a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥7, or active bleeding. A more detailed overview of the in- and exclusion criteria is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. In- and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| 1. ≥18 years of age |

| 2. Successful PCI |

| 3. History of or newly diagnosed (<72 hours after PCI/ACS) atrial fibrillation or flutter with a long-term (≥1 year) indication for OAC |

| Exclusion criteria |

| 1. Contraindication to edoxaban, aspirin or all P2Y12 inhibitors (e.g., kidney failure [eGFR <15 mL/min] or allergy) |

| 2. Any stroke <12 months |

| 3. History of intracranial haemorrhage |

| 4. Current indication for OAC besides atrial fibrillation/flutter (e.g., venous thromboembolism, mechanical heart valve prosthesis, intracardiac thrombus or apical aneurysm requiring OAC) |

| 5. Moderate to severe mitral valve stenosis (MVA ≤1.5 cm2) |

| 6. Life expectancy <1 year |

| 7. Active liver disease (ALT, ASP, AP >3x ULN or active hepatitis A, B or C) |

| 8. Active malignancy with metastases or undergoing non-curative treatments (e.g., palliative chemotherapy) |

| 9. Known coagulopathy |

| 10. Active bleeding on randomisation |

| 11. History of intraocular, spinal, retroperitoneal, or traumatic intra-articular bleeding, unless the causative factor has been permanently resolved |

| 12. Recent (<1 month) gastrointestinal haemorrhage, unless the causative factor has been permanently resolved |

| 13. Severe anaemia requiring blood transfusion or thrombocytopaenia <50×109/L |

| 14. Pregnancy or breastfeeding women |

| 15. BMI >40 or bariatric surgery |

| 16. Poor LV function (LVEF <30%) with proven slow flow |

| 17. CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥7 |

| 18. Oral anticoagulant other than NOAC or acenocoumarole (e.g., phenprocoumon) |

| ACS: acute coronary syndrome; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AP: alkaline phosphatase; ASP: aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: body mass index; CK: creatinine kinase; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LV: left ventricle; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MVA: mitral valve area; NOAC: non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; OAC: oral anticoagulation; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; ULN: upper limit of normal |

RANDOMISATION AND TREATMENT

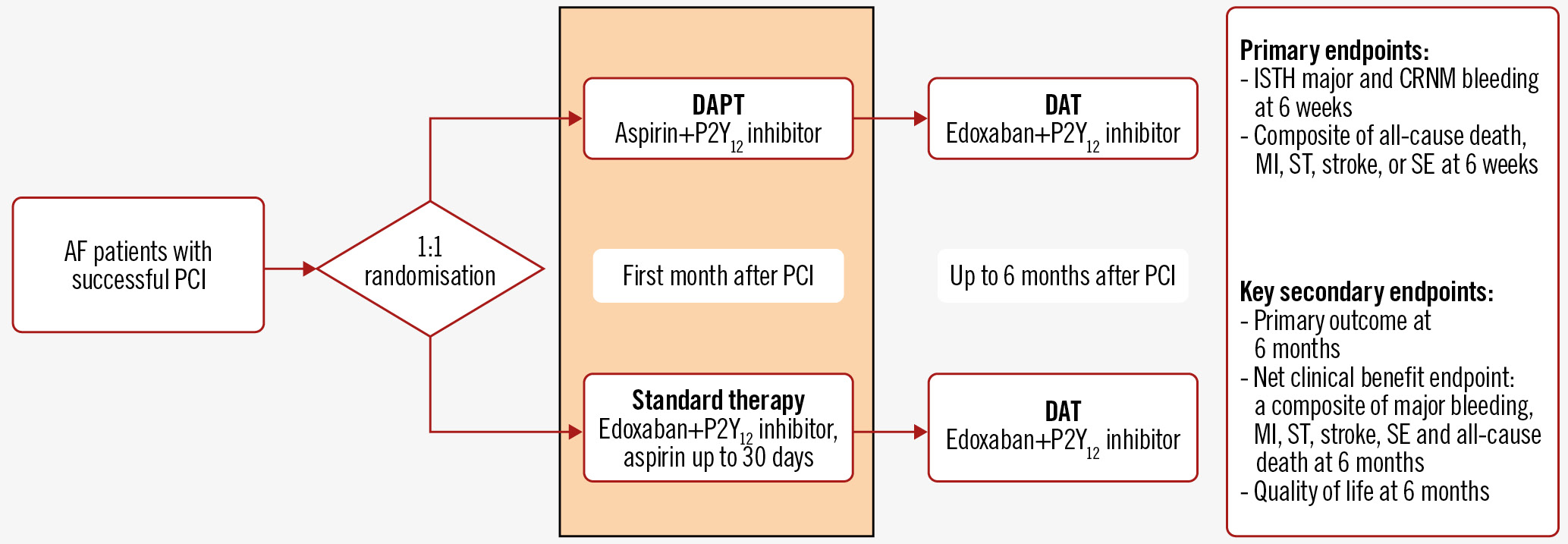

Eligible patients will be randomised and centrally allocated 1:1 to either the interventional or standard group via a computer-generated sequence, stratified by site and clinical presentation, i.e., ACS or elective PCI. Randomisation will be performed as early as possible, within 72 hours post-PCI. Patients in the interventional group will be treated with 30 days of DAPT, i.e., aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor, immediately discontinuing OAC. After 30 days, patients will be switched to standard therapy, i.e., NOAC and a P2Y12 inhibitor. Patients in the standard therapy group will be treated with guideline-directed therapy, i.e., NOAC plus a P2Y12 inhibitor plus a limited duration of aspirin, up to a maximum of 30 days at the discretion of the treating physician. A schematic overview of the study design is presented in Figure 1.

Edoxaban is the NOAC of choice for the sake of uniformity, as well as its once-daily dosing, and, together with apixaban, its association with fewer gastrointestinal bleeding events15. The recommended dose is 60 mg once daily unless one or more of the following criteria for the reduced dose of 30 mg once daily are met: moderate-to-severe kidney dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate 15-50 ml/min/1.73 m2), low body weight (<60 kg) or concomitant use of one of the following P-glycoprotein inhibitors: ciclosporin, dronedarone, erythromycin or ketoconazole.

Selection of the P2Y12 inhibitor is at the discretion of the treating physician. Genotyping or platelet-function testing may be used to guide decision-making. Permissible daily doses of P2Y12 inhibitors include clopidogrel 75 mg once daily, ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily, and prasugrel 10 mg once daily, or a reduced dose of 5 mg in patients aged ≥75 years or patients with low body weight (<60 kg). The daily aspirin dose is 75-100 mg.

The antithrombotic strategy before or during PCI − including the administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, bivalirudin or heparin − as well as invasive diagnostics and PCI techniques, are all at the treating physician’s discretion.

Figure 1. Study design and outcome measures. AF patients with a successful PCI will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to DAPT (aspirin+P2Y12 inhibitor) versus standard therapy (edoxaban+P2Y12 inhibitor+aspirin up to 30 days) in the first month after PCI, followed by DAT (edoxaban+P2Y12 inhibitor). AF: atrial fibrillation; CRNM: clinically relevant non-major; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DAT: dual antithrombotic therapy; ISTH: International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SE: systemic embolism; ST: stent thrombosis

PATIENT FOLLOW-UP

Efficacy and safety endpoints will be evaluated at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after randomisation and recorded in an electronic case report form. Endpoint evaluation will be conducted remotely through medical file reviewing and patient questionnaires on clinical events, self-reported adherence to study medication, and the EuroQol 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) quality of life questionnaire. If necessary, patients may be contacted by phone.

STUDY ENDPOINTS

The primary safety endpoint is major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding, as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH), at 6 weeks after randomisation. The co-primary efficacy endpoint is a composite of all-cause death, MI, stroke, systemic embolism, or (probable or definite) ST at 6 weeks after randomisation.

Key prespecified secondary endpoints are the primary safety and efficacy outcomes at 6 months after randomisation. Other secondary endpoints include the individual components of the 2 primary endpoints, as well as quality of life, and a net clinical benefit endpoint comprising major bleeding, stroke, systemic embolism, all-cause death, MI, and (probable or definite) ST at 6-week, 3-month, and 6-month follow-up. Bleeding is defined according to the ISTH and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) bleeding classifications to ensure comparability with prior and forthcoming publications. Detailed definitions of the components of the primary endpoints are provided in Supplementary Appendix 2.

SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

This study is designed to test both safety and efficacy hypotheses in AF patients requiring OAC and undergoing PCI: a 30-day DAPT regimen post-PCI followed by DAT is (1) superior to guideline-directed therapy in reducing bleeding risk and (2) non-inferior to guideline-directed therapy in the composite ischaemic endpoint. Since 2 co-primary endpoints are being utilised, statistical correction will be applied for the dual assessment. Trial success will be defined by the fulfilment of both hypotheses.

We used a web-based power calculator based on “Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research” by Chow et al19. Based on the AUGUSTUS trial, the anticipated bleeding rate in the standard treatment group is 7.45% at 30 days after ACS or elective PCI14. Hansen et al showed a hazard ratio of 1.88 for bleeding events in patients treated with OAC plus clopidogrel versus DAPT20. Therefore the assumed incidence for bleeding in the DAPT group is 4.01%. To achieve 80% power for superiority of the primary bleeding endpoint, 1,962 patients will be included, using a 1-sided significance level of 0.025.

This sample size will also ensure sufficient power to establish non-inferiority for the composite ischaemic endpoint. Based on the AUGUSTUS trial, the expected ischaemic event rate at 30 days is 1.66% in the interventional group and 2.57% in the standard group. If there is a true difference in favour of the experimental treatment of 1% (2.5% vs 1.5%), then 1,538 patients are required in order to be 80% sure that the upper limit of a 1-sided 97.5% CI will exclude a difference in favour of the standard group of more than 1%. To account for dropout, we will include 2,000 patients.

An intention-to-treat analysis will be performed for the primary endpoints. Per-protocol analysis will be used as a sensitivity analysis. Primary and secondary endpoint analyses will be based on the time of randomisation to the first occurrence of any event in the composite endpoint using Kaplan-Meier cumulative event-free curves and compared by means of the log-rank test.

Prespecified subgroup analyses of the primary and secondary endpoints will be performed to investigate the consistency of treatment effects across subgroups of clinical importance, including type of AF, type of index event, type and dose of P2Y12 inhibitor, the presence of CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles, NOAC dose, (planned) duration of TAT and DAT, medical history, sex, and procedural characteristics (e.g., number of diseased vessels, number of stents, and total stent length) including high-risk characteristics (e.g., left main stenting, treatment of a chronic total occlusion or bifurcation with 2 stents implanted) according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines21.

STUDY ORGANISATION

WOEST-3 is an investigator-initiated clinical trial sponsored by the St. Antonius Hospital Research Fund and Daiichi Sankyo. The Executive Committee is solely responsible for the design, conduct, analysis and reporting of this study.

DATA SAFETY MONITORING BOARD

An independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) has been established to assess the accumulating study data for safety. The DSMB reviewed the study protocol, may decide to perform an interim analysis, and may recommend early termination of the trial if interim findings convincingly favour or oppose a trial arm.

CLINICAL EVENT COMMITTEE

Clinical event classifications of the following study endpoints will be adjudicated by a blinded clinical endpoint committee prior to presentation of the data to the DSMB: death, bleeding, stroke, MI, ST, systemic embolism, and coronary revascularisation.

Discussion

The What is the Optimal antiplatElet & Anticoagulant Therapy in Patients With Oral Anticoagulation and Coronary StenTing (WOEST) trial was the first study to demonstrate that, compared to TAT, DAT (VKA plus clopidogrel) was associated with a significantly lower rate of bleeding, with no apparent increase in ischaemic events10. More recently, NOACs replaced VKA in AF patients owing to their safer bleeding profile and similar efficacy3. The subsequent, pivotal NOAC-based DAT trials demonstrated reduced bleeding complications compared to conventional TAT11121314. Notably, none of these trials were powered to assess ischaemic endpoints. Although several meta-analyses concluded that DAT reduced bleeding risk, this was counterbalanced by an increase in coronary ischaemic events1722. A post hoc analysis of the AUGUSTUS trial revealed that most ST occurred in the first month post-PCI18 and that the beneficial effect of aspirin is confined to this first month, after which its continued use caused more severe bleeding events but did not reduce severe coronary ischaemic events23. These findings carry important clinical implications and sparked debate on its use and duration in the early post-PCI phase.

The temporary omission of OAC in WOEST-3 allows for DAPT in the post-PCI phase, offering 2 major benefits. Firstly, we know that bleeding risk is significantly lower on DAPT than DAT, leading to a reduction in bleeding events in the post-PCI phase2024. Secondly, DAPT stands as the cornerstone treatment post-PCI, ensuring optimal coronary protection against ischaemic events during the critical 30-day period, which coincides with the peak occurrence of coronary events.

Omitting OAC in AF patients may be controversial, since the Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE) W parallel trial showed that warfarin was superior to DAPT for major cardiovascular event prevention (RR 1.44, 95% CI: 1.18-1.76)25. However, from the Stroke Preventions in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) and the ACTIVE A trials we know that aspirin versus placebo and DAPT versus aspirin, respectively, are both effective in reducing stroke risk in AF patients2627. Since the annual incidence of ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism remain low using DAPT, the annual risk difference between OAC and DAPT in the ACTIVE W trial was only 1%, and OAC interruption will be limited to only 30 days, we hypothesise that a short course of DAPT, rather than guideline-directed therapy, is non-inferior concerning stroke or systemic embolism.

The Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients Who Require Temporary Interruption of Warfarin Therapy for an Elective Invasive Procedure or Surgery (BRIDGE) trial has already shown that completely omitting OAC for 1 week was non-inferior compared to bridging with heparin in patients on warfarin undergoing surgery28. Moreover, this temporary interruption of OAC will allow for the use of aspirin in the first month post-PCI, when both coronary and haemorrhagic risks are greatest2329. As stroke risk is continuous over time and both bleeding and ischaemic risk are highest within the first 30 days but decline thereafter, the risk of bleeding or ischaemic events on TAT followed by DAT probably outweighs the risk of stroke on DAPT within the first month.

Several ongoing trials are currently exploring the optimal antithrombotic strategy in AF-PCI patients. The ADONIS-PCI trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04695106) and OPTIMA-4 substudy (NCT03234114) are investigating the impact of more potent P2Y12 inhibitors in NOAC-based DAT on bleeding and ischaemic risk. The EPIDAURUS trial (NCT04981041) investigates de-escalation of an early intensive antithrombotic strategy. Notably, the MATRIX-2 trial (NCT05955365) shares a similar rationale with our trial, albeit more innovative, treating patients with 1 month of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy followed by NOAC monotherapy.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge limitations within our trial. Firstly, the NOAC used in this study is edoxaban, which may limit the generalisability of our findings to other NOACs. Secondly, the choice of P2Y12 inhibitor is left to the discretion of the investigator (although clopidogrel is the preferred drug), potentially introducing variability in treatment regimens. A prespecified subgroup analysis will be performed on the choice of P2Y12 inhibitor. Despite these limitations, the insights gained from our trial will contribute valuable knowledge to the ongoing pursuit of the optimal antithrombotic strategy in AF-PCI.

Conclusions

The WOEST-3 trial is the first randomised controlled, multicentre trial assessing the safety and efficacy of a 30-day DAPT strategy post-PCI in patients with AF and a long-term indication for OAC. Although recent RCTs demonstrated significantly fewer bleeding events with DAT when compared to TAT, bleeding rates remain high, and the omission of aspirin may lead to an increase in the incidence of ST and MI. Therefore, in WOEST-3, temporary OAC omission allows for a short course of DAPT. This may not only decrease bleeding risk but also provides optimal coronary protection against ischaemic events during the first 30 days post-PCI.

Funding

Funding was provided by the St. Antonius Hospital Research Fund, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, and Daiichi Sankyo.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no specific conflicts of interest to declare with respect to this manuscript.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.