Abstract

Background: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in patients with small aortic annuli (SAA) is associated with an increased risk of prosthesis-patient mismatch (PPM).

Aims: This study assesses the 30-day performance of the novel balloon-expandable DurAVR transcatheter heart valve (THV), which features a unique single-piece biomimetic leaflet design, in patients with SAA.

Methods: This pooled analysis derived from first-in-human and early feasibility studies includes all patients with SAA (defined as an aortic annular area from 346 mm2 to 452 mm2) treated with the small-sized DurAVR THV. The mean computed tomography (CT)-derived aortic annulus area was 404±37 mm2, with a mean diameter of 22.7±1.0 mm. Outcomes at 30 days, including PPM, were evaluated per Valve Academic Research Consortium 3 criteria, with independent adjudication of clinical events and core laboratory analysis of post-implant transthoracic echocardiograms.

Results: Amongst 100 patients (mean age 77.0±7.3 years; 78% female; mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons score 4.7±4.0%) treated with the DurAVR THV, the overall technical success rate was 93%. At 30 days, device success was achieved in 91% of patients, with no reported deaths and a stroke rate of 2%. Echocardiographic haemodynamic assessment showed a mean transprosthetic gradient of 8.2±3.1 mmHg, a mean effective orifice area of 2.2±0.3 cm2, and a Doppler velocity index of 0.60±0.10. The incidence of moderate or greater PPM was 3%, and no patients experienced more than mild paravalvular leak. The rate of new permanent pacemaker implantation was 6%.

Conclusions: In patients with SAA, the DurAVR THV demonstrated promising clinical and echocardiographic outcomes at 30 days. Longer-term follow-up in larger cohorts is needed to confirm these encouraging early results.

As transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) increasingly extends to younger patients with longer life expectancies, factors such as haemodynamic valve performance, valve durability, and the feasibility for reintervention become even more critical1. Patients with small aortic annuli (SAA) undergoing TAVI often encounter suboptimal results, including elevated transprosthetic gradients, increased prosthesis-patient mismatch (PPM), and early bioprosthetic valve failure (BVF)2345. These outcomes can be influenced by the design of the transcatheter aortic valve (TAV), particularly differences in leaflet position, whether supra-annular or intra-annular, and leaflet design. However, existing data on this topic remain conflicting567891011.

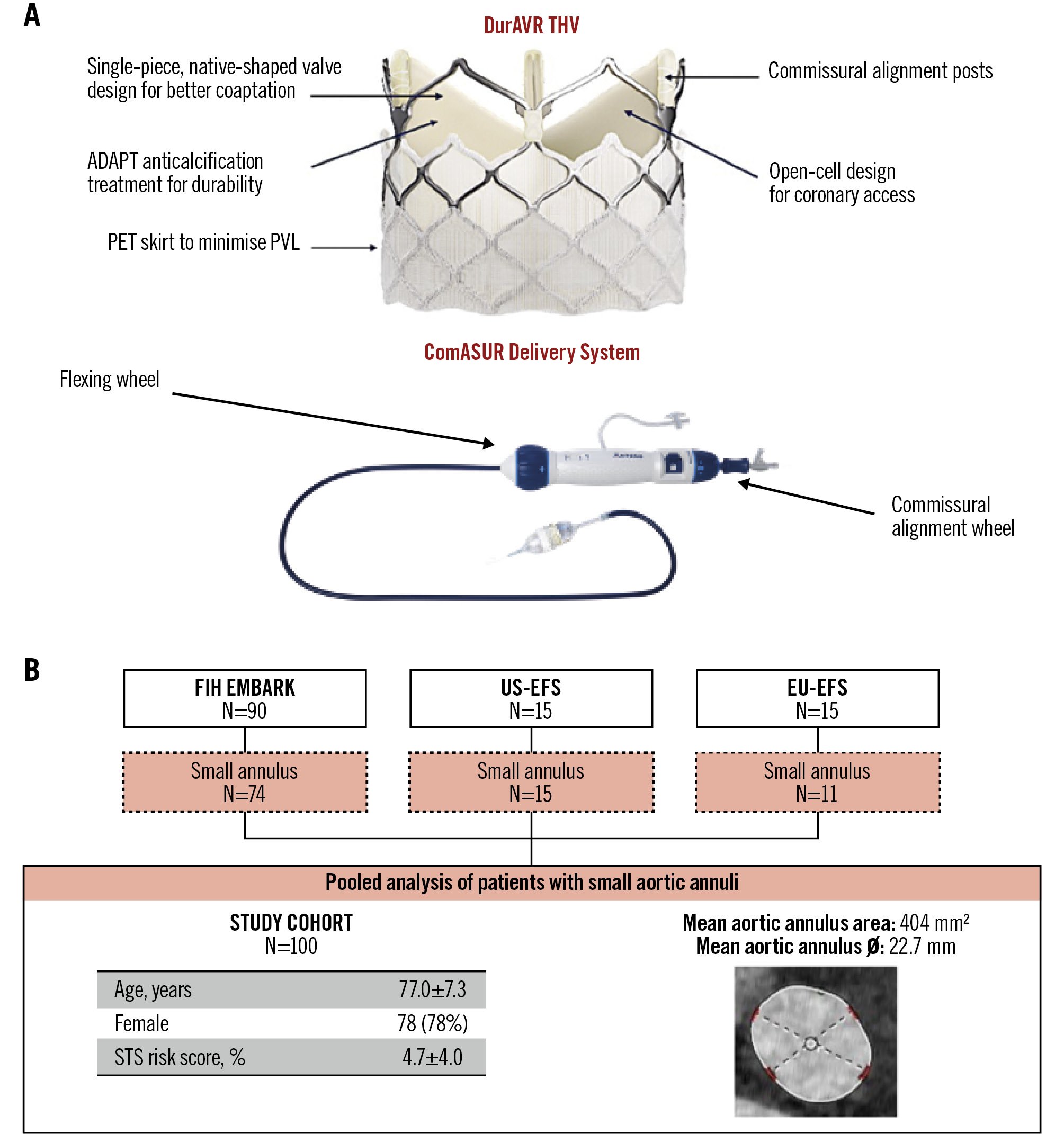

The DurAVR transcatheter heart valve (THV; Anteris Technologies) is a novel balloon-expandable valve featuring a unique first-of-its-kind single-piece biomimetic leaflet design. Early experience from first-in-human and early feasibility studies (EFS) have demonstrated promising results12. In this study, we report the procedural and 30-day clinical and haemodynamic outcomes for patients with SAA who underwent TAVI with the DurAVR THV.

Methods

Study cohort

All patients with severe aortic stenosis and an SAA, defined as a computed tomography (CT)-based aortic annular area of 346-452 mm2, who participated in the DurAVR: First-In-Human Study (EMBARK; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05182307), United States Early Feasibility Study (US-EFS; NCT05712161) and European Early Feasibility Study (EU-EFS; NCT06510855) were pooled together to constitute the study population for this analysis. The EMBARK First-in-Human study was a prospective, single-arm, single-centre study enrolling 90 patients from November 2021 to May 2025. The US-EFS was a prospective, single-arm study enrolling 15 patients across 4 sites between August and October 2023. The EU-EFS was a prospective, single-arm study enrolling 15 patients at a single centre between January and June 2025. The study protocols were approved by national regulatory authorities and the institutional ethical committees at the participating sites, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Device description

The DurAVR THV features a balloon-expandable stent frame encompassing a single piece of bovine pericardial tissue moulded into a trileaflet configuration to mimic native aortic valve geometry (Figure 1). The bovine pericardium is treated with a proprietary ADAPT anticalcification tissue engineering process, which was developed to reduce the antigens responsible for inflammation and calcification13. This process enhances leaflet elasticity and strength, resulting in a valve performance comparable to healthy native leaflets14. The DurAVR stent frame consists of a top row of large open cells for ease of coronary access, radiopaque markers to facilitate valve positioning and commissural alignment, and a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) skirt to minimise paravalvular leak (PVL). The DurAVR THV is crimped onto a balloon-expandable catheter and delivered via the transfemoral ComASUR Delivery System (Anteris Technologies). The system comprises a flexible steering catheter and a commissural wheel that enables 1:1 rotational torque, facilitating patient-specific commissural alignment.

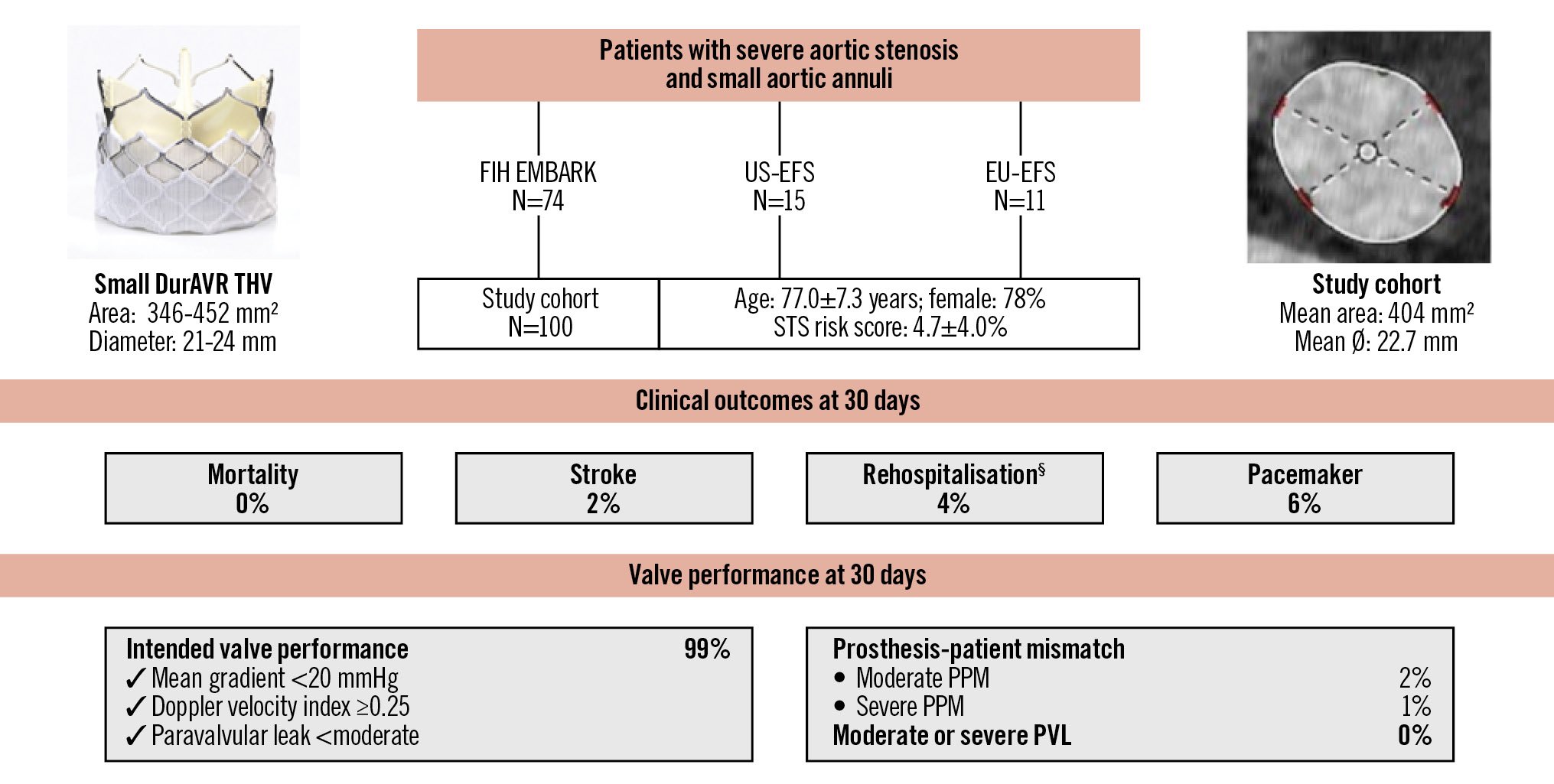

Figure 1. DurAVR THV and study cohort. A) The DurAVR transcatheter heart valve (THV) is a short-frame, balloon-expandable valve featuring a novel single-leaflet, native-shaped biomimetic leaflet design that replicates native aortic valve leaflets. The valve is delivered using the dedicated ComASUR Delivery System, which permits active patient-specific commissural alignment. B) The study cohort comprises all patients with a small aortic annulus treated in the first-in-human and early feasibility studies. EFS: early feasibility study; EU: European; FIH: first-in-human; PET: polyethylene terephthalate; PVL: paravalvular leak; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Implant procedure

Patient eligibility for DurAVR THV implantation was determined by the respective Heart Teams at each site and the study screening committees. All patients received a small DurAVR THV, suitable for treatment of native aortic annuli with an area-derived diameter of 21-24 mm and aortic annulus area of 346-452 mm2. The valve was deployed under fluoroscopic guidance during rapid pacing. Post-deployment assessments included stent frame expansion by fluoroscopy, haemodynamic function, and detection of aortic regurgitation. The overall procedural approach, including decisions regarding pre- or post-dilatation, use of cerebral embolic protection devices, vascular access closure methods, and postprocedural antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapy, was left to the discretion of the operator.

Data collection

Prospective data on baseline demographics, procedural details, and 30-day follow-up results were collected. An independent clinical event committee verified all events in the EFS studies, while independent physician adjudication was performed for the EMBARK study. Symptoms and quality of life were assessed at baseline and 30 days post-procedure using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ).

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed at baseline and 30 days after the procedure, with images analysed by dedicated core laboratories for the EMBARK (Acudoc Swedish Echo Core Lab, Acudoc Clinical Physiology Laboratories, Stockholm, Sweden) and US-EFS and EU-EFS cohorts (Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY, USA). Aortic stenosis severity was determined using the mean gradient, peak velocity, and aortic valve area (AVA). Post-procedure valve haemodynamics included measurements of transprosthetic gradient, effective orifice area (EOA), and Doppler velocity index (DVI). PPM severity was classified according to Valve Academic Research Consortium 3 (VARC-3) criteria: in patients with a body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2, moderate PPM was defined as an indexed EOA of 0.66-0.85 cm2/m2 and severe PPM was defined as ≤0.65 cm2/m2; in patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, moderate PPM was defined as an indexed EOA of 0.56-0.70 cm2/m2 and severe PPM was defined as ≤0.55 cm2/m215. Prosthetic aortic valve regurgitation (central and paravalvular) was graded per VARC-3 classification: none/trace, mild, moderate, or severe.

Study endpoints

All study endpoints were reported in accordance with VARC-3 criteria15. Technical success, assessed immediately upon exiting the procedure room, was defined as the absence of mortality, successful vascular access, proper delivery and deployment of the device, retrieval of the delivery system, correct positioning of a single prosthetic valve into the proper anatomical location, and absence of surgical or other interventions related to the device or major vascular, access-related, or cardiac structural complications. Safety endpoints were reported as per VARC-3 criteria. Clinical efficacy at 30 days was defined as the absence of all-cause mortality, stroke, hospitalisation related to the procedure or valve; a decline of less than 10 points in the overall KCCQ score from baseline; and no worsening of NYHA Class.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics, device performance, risk factors, and clinical outcomes are summarised using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables are expressed as means with standard deviations, while categorical variables are presented as counts and proportions. All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 30 (IBM).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 100 patients with SAA, derived from the EMBARK (n=74), US-EFS (n=15), and EU-EFS (n=11) cohorts, were included for analysis. Baseline characteristics are summarised in Table 1, with individual cohort details available in Supplementary Table 2. The mean age was 77.0±7.3 years, 78% were female, and the overall mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score was 4.7±4.0%. A total of 91% of patients had a tricuspid aortic valve, and 9% had a type 1 bicuspid aortic valve phenotype (8 patients with left-right fusion and 1 patient with non-right fusion). The CT-based mean aortic annulus area was 404±37 mm2, with a mean annulus diameter of 22.7±1.0 mm. The baseline mean aortic valve gradient was 48.1±17.0 mmHg and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 58.0±7.0%.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| N=100 | |

|---|---|

| Clinical variables | |

| Age, years | 77.0±7.3 |

| Female | 78 (78) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.6±5.1 |

| Arterial hypertension | 91 (91) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (33) |

| Coronary artery disease | 60 (60) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 12 (12) |

| Previous PCI | 36 (36) |

| Previous CABG | 7 (7) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2 (2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 12 (12) |

| Previous stroke | 1 (1) |

| Renal insufficiency or failure | 56 (56) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (3) |

| Previous pacemaker | 6 (6) |

| STS risk score, % | 4.7±4.0 |

| NYHA Class III or IV | 61 (61) |

| KCCQ overall summary score | 40.7±20.4 |

| Baseline echocardiographic data | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 58.0±7.0 |

| Mean transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 48.1±17.0 |

| Peak transvalvular gradient, mmHg | 78.3±26.8 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.8±0.2 |

| Aortic regurgitation ≥moderate, % | 6/99 (6) |

| Mitral regurgitation ≥moderate, % | 10/97 (11) |

| Baseline CT data | |

| Aortic annulus area, mm2 | 404±37 |

| Aortic annulus perimeter, mm | 72.0±3.5 |

| Aortic annulus mean diameter, mm | 22.7±1.0 |

| Sinotubular junction diameter, mm | 27.3±2.6 |

| Left coronary artery height, mm | 13.2±2.8 |

| Right coronary artery height, mm | 16.4±2.8 |

| Values are expressed as mean±SD, n (%) or n/N (%). CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CT: computed tomography; KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons | |

Procedural outcomes

Procedural data and outcomes are summarised in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. In the initial EMBARK study, most procedures (69%) were performed under general anaesthesia with transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) guidance. In contrast, in the more recent EU-EFS study, a minimalist approach using local anaesthesia and sedation was successfully adopted in 100% of procedures. The transfemoral access route was utilised for 94% of cases, while transaortic and transcarotid access routes were used in 5% and 1% of cases, respectively. Predilatation was performed in 57% of procedures, while post-dilatation was noted in 8% of procedures.

The overall VARC-3 defined technical success rate was 93%. Periprocedural complications were only encountered in the EMBARK first-in-human cohort, reflecting early device and operator experience (Supplementary Table 4). Subsequent refinements to the valve design, compliance of the inflation balloon, the delivery system, and the expandable sheath profile were implemented. In the last 50 consecutive implants, including the US-EFS and EU-EFS cohorts, no major periprocedural complications occurred, reflecting a technical success rate of 100% (Table 2).

Table 2.Procedural characteristics and technical success.

| N=100 | |

|---|---|

| Procedural characteristics | |

| Anaesthesia type | |

| General anaesthesia | 69 (69) |

| Conscious sedation/local anaesthesia | 31 (31) |

| Transfemoral access and delivery | 94 (94) |

| DurAVR THV small valve size | 100 (100) |

| Predilatation | 57 (57) |

| Post-dilatation | 8/95 (8) |

| Cerebral embolic protection device | 26 (26) |

| Procedural time, min | 24.3±20.8 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 18.5±8.9 |

| Use of contrast dye, mL | 91.2±31.2 |

| Technical success (VARC-3) | |

| Freedom from mortality | 100 (100) |

| Successful access, delivery of the device, and retrieval of the delivery system | 100 (100) |

| Correct positioning of a single THV into the proper anatomical location | 98 (98) |

| Freedom from surgery or intervention related to the device or to a major vascular, access-related, or cardiac structural complication | 95 (95) |

| Technical success at exit from procedure room | 93 (93) |

| FIH-EMBARK cohort − early experience | 67/74 (91) |

| US/EU-EFS cohort − later experience | 26/26 (100) |

| Values are presented as mean±SD or, n (%). EFS: early feasibility study; FIH: first-in-human; SD: standard deviation; THV: transcatheter heart valve; VARC: Valve Academic Research Consortium | |

Thirty-day clinical outcomes

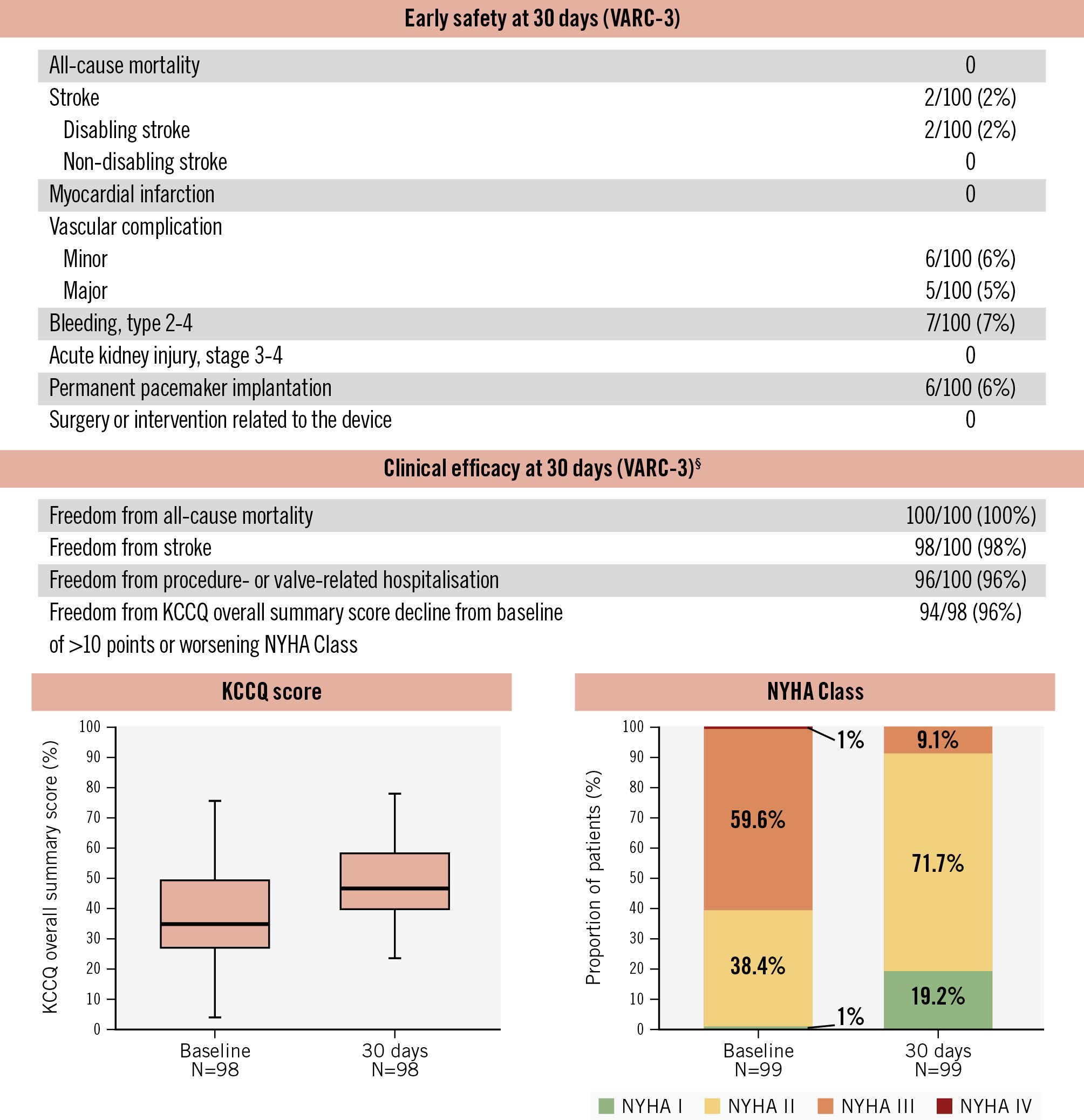

Complete 30-day follow-up was achieved in all patients (Figure 2). There were no deaths, and 2 patients experienced a stroke. Major vascular complications and bleeding (type 2-4) occurred in 5% and 7% of patients, respectively. Notably, none of these complications were observed in the US/EU-EFS cohorts. The overall rate of new permanent pacemaker implantation was 6%. Patients showed marked symptomatic improvement, with the KCCQ score increasing by 12 points from baseline. Additionally, 70% of patients reported an improvement in NYHA classification as early as 30 days.

Figure 2. Thirty-day clinical outcomes. High clinical safety, clinical efficacy, and improvement in symptoms were observed at 30 days following DurAVR THV implantation in patients with small aortic annuli. Paired analysis for KCCQ and NYHA scores. §Modified VARC-3 definition. KCCQ: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; NYHA: New York Heart Association; THV: transcatheter heart valve; VARC: Valve Academic Research Consortium

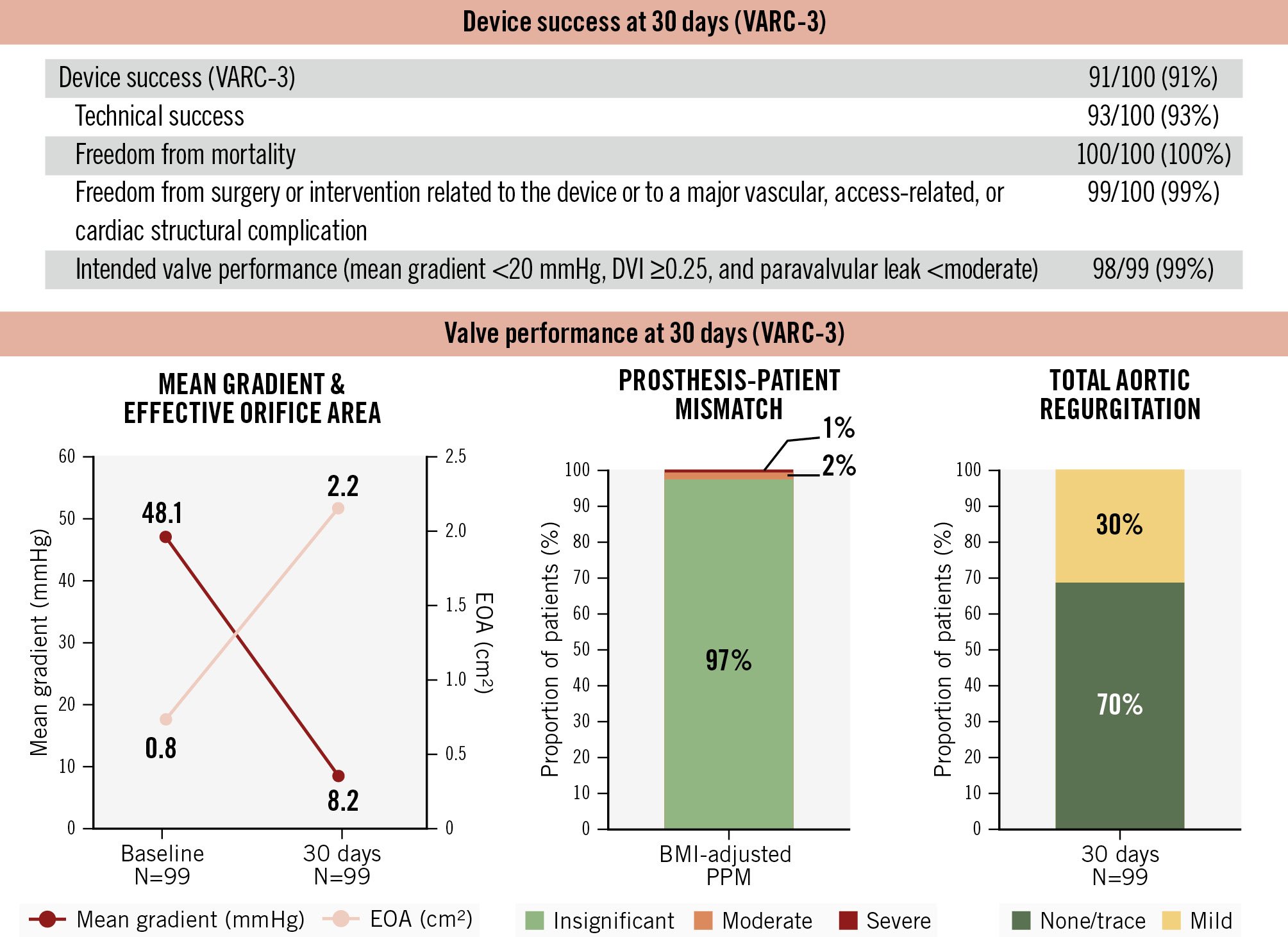

Valve performance

Device success per VARC-3 criteria was achieved in 91% of patients (Figure 3). One patient developed a late external iliac artery thrombus requiring vascular intervention, and one other patient exhibited a residual mean transprosthetic gradient >20 mmHg, attributed to leaflet thrombosis detected on post-TAVI CT imaging. At 30 days, the mean transprosthetic gradient was 8.2±3.1 mmHg, with a mean EOA of 2.2±0.3 cm2, and mean DVI of 0.60±0.10. The incidences of moderate and severe PPM were 2% and 1%, respectively. No patients had greater than mild PVL.

Figure 3. Thirty-day device success and valve performance. The DurAVR THV demonstrated high device success and favourable haemodynamic outcomes at 30 days post-procedure in patients with small aortic annuli. BMI: body mass index; DVI: Doppler velocity index; EOA: effective orifice area; PPM: prosthesis-patient mismatch; THV: transcatheter heart valve; VARC: Valve Academic Research Consortium

Discussion

This is the largest study to date reporting on clinical and echocardiographic outcomes following implantation of the novel biomimetic balloon-expandable DurAVR THV. Among 100 patients with SAA, we observed (1) a high rate of VARC-3-defined technical success (93%) and early clinical safety and efficacy; (2) favourable core-lab-assessed echocardiographic haemodynamic outcomes, including low mean transprosthetic gradients (8.2±3.1 mmHg), a large EOA (2.2±0.3 cm2), only 3% of patients with moderate or greater PPM, and no cases of greater than mild PVL; and (3) a permanent pacemaker implantation rate of 6% (Central illustration). It should be noted that these outcomes were derived from a mixed cohort, including first-in-human and early feasibility studies. In more recent US-EFS and EU-EFS cohorts, the DurAVR THV system demonstrated a 100% technical success rate, which compares favourably with current-generation TAVI systems when treating patients with SAA.

Central illustration. Outcomes of the biomimetic balloon-expandable DurAVR THV in small aortic annuli. VARC-3-defined clinical outcomes and valve performance at 30 days after DurAVR THV implantation in a patient population with small aortic annuli. §Procedure- and valve-related hospitalisations. PPM: prosthesis-patient mismatch; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons; THV: transcatheter heart valve; VARC: Valve Academic Research Consortium

Challenges of small aortic annuli

Surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with SAA often results in high postoperative mean transprosthetic gradients, small EOAs, and a high incidence of PPM, factors linked to increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalisations, and bioprosthetic valve degeneration (BVD)161718. Similarly, TAVI outcomes are affected by the presence of SAA, which are associated with higher residual gradients, increased PPM, and poorer clinical outcomes61920. Data from the STS/ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) Registry showed that among 62,125 patients who underwent TAVI between 2014 and 2017, the incidences of moderate and severe PPM were 25% and 12%, respectively, and these were linked with increased mortality risk (hazard ratio [HR] 1.19, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.09-1.31; p<0.001) and heart failure hospitalisation (HR 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02-1.24; p<0.001) at 1-year follow-up2. Furthermore, the European Valve Durability TAVI Registry noted higher rates of structural valve deterioration (SVD) at a median follow-up of 6.1 years with smaller TAVs (HR 4.8, 95% CI: 2.42-9.60; p<0.001)21.

Impact of transcatheter aortic valve design

Not all TAVI devices perform equally in patients with SAA; outcomes vary significantly based on the valve design. The retrospective multicentre TAVI-SMALL 2 registry, involving 1,378 patients with SAA, reported that self-expanding valves (SEVs), compared to balloon-expandable valves (BEVs), were associated with lower mean transprosthetic gradients (8.0±4.1 mmHg vs 13.6±4.7 mmHg; p<0.001) and lower rates of PPM (4.6% vs 8.7%)7. Similarly, the Bern TAVI Registry, after propensity matching 723 patients with SAA, reported severe PPM in 19.7% with SEVs versus 51.8% with BEVs9. These findings have been consistent across studies involving both older- and newer-generation TAVs as well as in patients with extra-small annuli811. The SMART Trial, a randomised controlled trial comparing SAA patients receiving Evolut (SEV; Medtronic) or SAPIEN (BEV; Edwards Lifesciences) valves, demonstrated that SEV implantation was associated with a significantly lower incidence of mean transprosthetic gradients ≥20 mmHg (3.2% vs 32.2%), reduced moderate or greater PPM (11.2% vs 35.3%; p<0.001), and subsequently, lower rates of SVD (3.5% vs 32.8%) and BVD (10.2% vs 43.3%) at 1 year5. However, these haemodynamic advantages of SEVs come with trade-offs, including higher rates of PVL and permanent pacemaker implantation7911.

DurAVR THV for small aortic annuli

In this study, we demonstrated that the balloon-expandable DurAVR THV exhibits favourable haemodynamic valve performance in patients with SAA. Specifically, low mean transprosthetic gradients (8.2±3.1 mmHg), high EOAs (2.2±0.3 cm2), and very low incidences of moderate (2%) and severe (1%) PPM were observed. Additionally, the rates of core-lab-assessed PVL were minimal, with no patients experiencing more than mild PVL. The need for new permanent pacemaker implantation was only 6%. This early experience suggests that the combination of BEV-like performance − characterised by high device success and low pacemaker implantation rates − alongside SEV-like haemodynamics makes the DurAVR THV an attractive new option for patients with SAA. The favourable haemodynamic profile may be attributed to its innovative biomimetic leaflet design. The DurAVR THV leaflets are made from a single piece of bovine pericardial tissue, treated with the proprietary ADAPT anticalcification tissue engineering process and shaped to mimic a native aortic valve. This design results in a longer leaflet coaptation length (~7 mm), allowing the valve to replicate the natural geometry and kinematics of a native aortic valve. In contrast, conventional TAVs have three separate leaflets sutured to the stent frame, often leading to smaller orifice areas and abnormal blood flow patterns in the ascending aorta22.

Cardiac magnetic resonance flow studies support these findings, demonstrating that DurAVR THV restores near-normal laminar flow in the aorta, comparable to healthy valves12. Further research is needed to determine the impact that restoration of laminar flow can have on left ventricular mass regression, which is often impaired in SAA patients with PPM, and the risk of neosinus or leaflet thrombosis23. These factors could influence the long-term durability of the valve, especially as TAVI is increasingly used in younger patients with longer life expectancy, where considerations such as coronary reaccess and the feasibility of redo-TAVI are crucial for lifelong management. Patients with small aortic roots are at higher risk for challenging coronary access or redo interventions, and the short-frame design and ability to achieve patient-specific commissural alignment represent significant advantages of the DurAVR THV.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size included both very early first-in-human procedures and more recent implants, reflecting a learning curve and device improvements over time. This progression is evident in the better safety profile and technical success observed in the EFS cohorts compared to the EMBARK cohort. Second, this report describes haemodynamic performance at 30 days post-procedure; longer-term data are needed to confirm valve durability. Lastly, without a comparator group, it is difficult to directly compare DurAVR THV performance to that of other current-generation TAVs. However, this will be addressed in the upcoming PARADIGM randomised controlled trial (ClinicalTrials: NCT07194265), which will compare the DurAVR THV with commercially available TAV systems in a broad patient population with severe aortic stenosis.

Conclusions

The biomimetic balloon-expandable DurAVR THV demonstrated high rates of technical and device success, along with favourable haemodynamic outcomes at 30 days, including a low incidence of PPM in patients with SAA. Further studies are necessary to confirm its long-term durability.

Impact on daily practice

The DurAVR transcatheter heart valve (THV) is a balloon-expandable valve featuring a single-piece biomimetic leaflet design and was associated with favourable 30-day haemodynamic performance in patients with small aortic annuli. Ongoing randomised controlled trials will further evaluate DurAVR THV advantages compared to current-generation THVs and explore how its biomimetic design might improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Nick Bates, Angela McGonagle, Laurence Milon, Souhelia Moutiq, Marie Ollivry, Tanya Schikorr, and Silvia Zinicchino (Anteris Technologies), who supported the conduct of these studies and assisted with data collection for the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

O. De Backer received institutional research grants and consulting fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. A.A. Khokhar received speaker fees/honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. G. Bieliauskas has received speaker honoraria and consulting fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Sahajanand Medical Technologies Ltd. A. Latib is a consultant for Medtronic; and received speaker honoraria from Medtronic and Biotronik. R. Puri is a consultant, speaker and proctor for Medtronic and Abbott; consults for Centerline Biomedical, Philips, Products & Features, Shockwave Medical, VDyne, VahatiCor, Advanced NanoTherapies, NuevoSono, TherOx, GE HealthCare, Anteris Technologies, T45 Labs, Pi-Cardia, Protembis, and Nyra Medical; and has equity interest in Centerline Biomedical, VahatiCor, and NuevoSono. A. Asgar has been a consultant for/on an advisory board for Medtronic and Abbott; and has been a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences. S.A. Garcia is supported by The Harold C. Schott Foundation Endowed Chair for Structural and Valvular Heart Disease; and is a proctor and steering committee member for Edwards Lifesciences. R.T. Hahn reports speaker fees from Abbott, Baylis Medical, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Philips, and Siemens Healthineers; institutional consulting contracts, for which she receives no direct compensation, with Abbott, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Novartis; and she is Chief Scientific Officer for the Echocardiography Core Laboratory at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation for multiple industry-sponsored tricuspid valve trials, for which she receives no direct industry compensation. P. D. Mahoney is a consultant and proctor for Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, and Boston Scientific; is a consultant for Abbott; and has been awarded research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific. T. Waggoner served as a consultant and received research grants from Abbott, Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic; received educational grants from Philips; and is a shareholder in Corstasis. S. Chetcuti reports personal fees from Medtronic; grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific, and JenaValve (paid to the institution) during the conduct of the study; and being on the advisory board for BioTrace and JenaValve, without remuneration. W.-K. Kim reports personal fees from Abbott, Anteris Technologies, Boston Scientific, Cardiawave, Edwards Lifesciences, Hi-D Imaging, JenaValve, Meril Life Sciences, and Products & Features; and institutional fees from Boston Scientific. J.L. Cavalcante has served on advisory boards for Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic; received consulting fees from 4C Medical Technologies, Anteris Technologies, Abbott, Aria CV, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, JenaValve Technology, Medtronic, VDyne, W.L. Gore & Associates, and XyloCor; and received research/grant support from Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation and Abbott. K. Feldt has received consulting fees from Anteris Technologies and Alleviant Medical; payment or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Abbott; and has participated on an advisory board at Amgen. C.U. Meduri is the CMO at Anteris Technologies; received grants/research support from Boston Scientific; and received honoraria/consultation fees from Abbott, Alleviant Medical, Boston Scientific, Cardiovalve, VDyne, and xDot Medical. D. Meier has received an institutional grant from Edwards Lifesciences; and is a consultant for Anteris Technologies and Abbott. J.J. Popma was a former employee of Medtronic (<24 months). S. Windecker reports research, travel and/or educational grants to the institution from Abbott, Abiomed, Alnylam, Amicus Therapeutics, Amgen, Anteris Technologies, AstraZeneca, Bayer, B. Braun, Bioanalytica, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cordis Medical, CorFlow Therapeutics, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Fumedica, GE HealthCare, Guerbet, IACULIS, Inari Medical, Janssen AI, Johnson & Johnson, Medalliance, Medtronic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Neovii Pharmaceuticals, Neutromedics AG, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, OM Pharma, Optimapharm, Orchestra BioMed, Pfizer, Philips AG, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shockwave Medical, Siemens Healthineers, Sinomed, Sahajanand Medical Technologies, Vascular Medical, and V-Wave; and serves as an advisory board member and/or member of the steering/executive group of trials funded by Abbott, Amgen, Anteris Technologies, Abiomed, Edwards Lifesciences, EnCarda Inc., Medtronic, Novartis, and Sinomed, with payments to the institution but no personal payments; and he is also a member of the steering/executive committee group of several investigator-initiated trials that receive funding from industry without impact on his personal remuneration. M.J. Reardon has received fees to his institution from Medtronic for consulting and providing educational services. V.N. Bapat received consulting fees from Anteris Technologies, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. The other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.