Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) results from architectural abnormalities or the inability of the coronary microvasculature to vasodilate, both leading to angina, dyspnoea or reduced exercise capacity1. Understanding CMD mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted therapies and improving prognosis. Two CMD endotypes, “structural” and “functional”, were recently identified through the combined assessment of coronary flow reserve (CFR) and minimal microvascular resistance using bolus thermodilution with adenosine-induced hyperaemia2. This study aims to characterise different CMD phenotypes by assessing adaptation to incremental cycling exercise in the cath lab among participants with suspected angina with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (ANOCA).

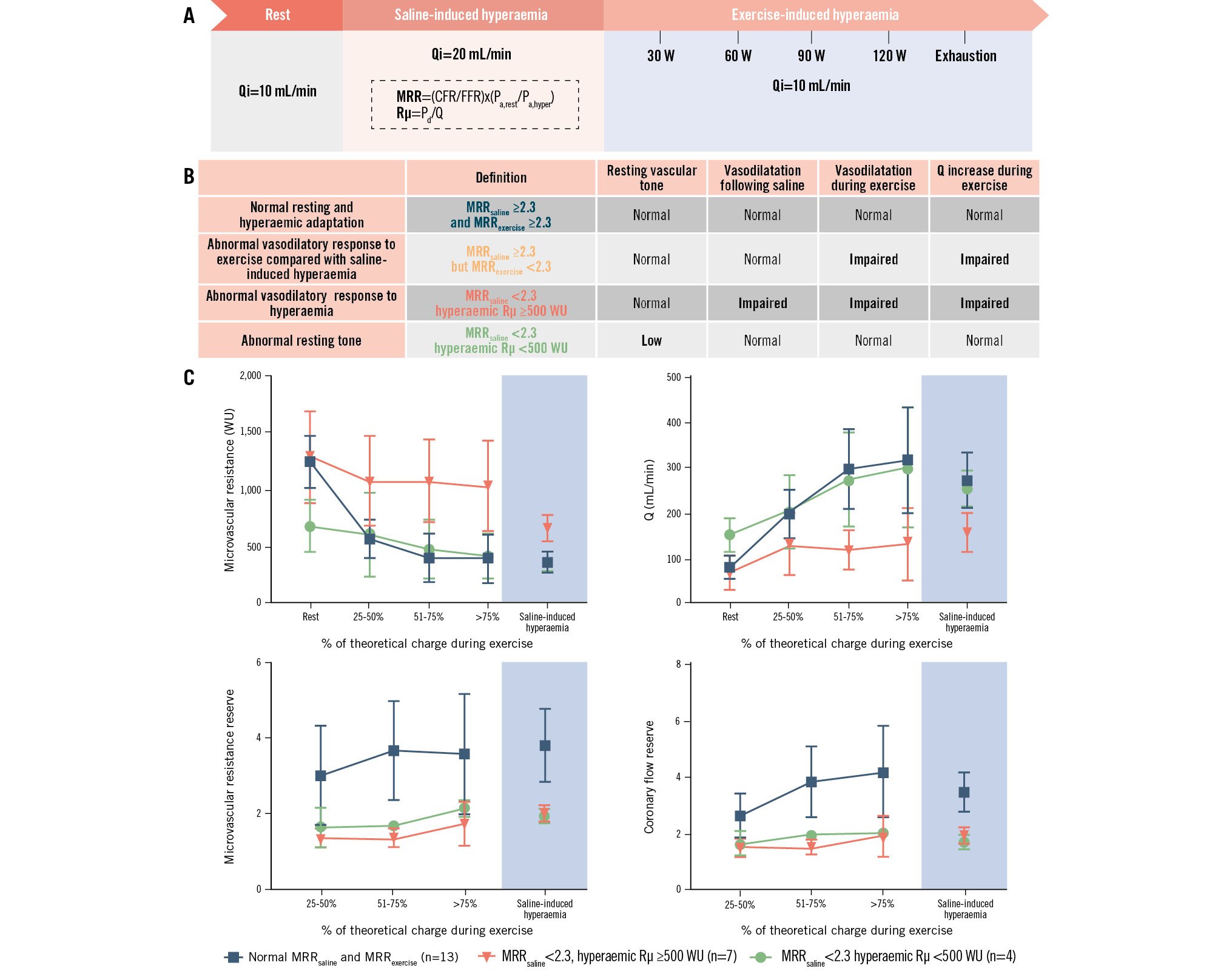

Absolute microvascular resistance (Rμ), absolute coronary blood flow (Q), microvascular resistance reserve (MRR) and CFR were measured in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) using continuous thermodilution. Saline was infused at 10 mL/min (rest) and at 20 mL/min (hyperaemia) to assess MRRsaline. The presence of CMD was defined as an MRRsaline <2.33. Hyperaemic Rμ was classified as normal (<500 Wood units [WU]) or elevated (≥500 WU) based on saline-induced hyperaemia4. In addition, patients performed the cycling exercise using a supine cycling ergometer (ERG 911 BP/X-RAY [SCHILLER]) with an increasing workload of 30 watts every two minutes. During exercise, measurements were performed with a saline infusion rate of 10 mL/min to assess the peak exercise MRRexercise (Central illustration). The maximal theoretical exercise capacity was calculated for each patient using the formulas metabolic equivalents of task (METs)=18–(0.15*age) for males and 14.7–(0.13*age) for females. Haemodynamic data were analysed offline using CoroFlow (Coroventis). This study was approved by the local ethics committee (CER-PINOCA) of Sorbonne University. It was supported and driven by the ACTION Study Group. All individuals provided oral and written informed consent before enrolment.

We included 30 consecutive outpatients suspected of having ANOCA between May 2022 and June 2023. Among them, 11 participants had MRRsaline-defined CMD. These participants were predominantly female (81.8%) with a mean age of 62.4 years old and a high prevalence of arterial hypertension (81.8%), dyslipidaemia (72.7%), and chronic inflammatory diseases (36.4%) (Supplementary Table 1). When using physiological exercise combined with continuous thermodilution, we identified four distinct phenotypes (Central illustration, Supplementary Figure 1). 1) Participants with both normal MRRsaline and MRRexercise (n=13) displayed a normal reference resting vascular tone and microvascular adaptation to saline- and exercise-induced hyperaemia. 2) Participants with normal MRRsaline but impaired MRRexercise <2.3 (n=6) exhibited an impaired vasodilatory response to exercise despite a normal response to saline-induced hyperaemia. 3) Participants with MRRsaline <2.3 and hyperaemic Rμ ≥500 WU (n=7) displayed an impaired vasodilatory response to both saline- and exercise-induced hyperaemia. 4) Participants with MRRsaline <2.3 and hyperaemic Rμ <500 WU (n=4) exhibited a low resting microvascular tone but an adapted vasodilatory response to both saline- and exercise-induced hyperaemia.

Physiological exercise combined with continuous thermodilution provided a refined analysis of CMD mechanisms. A key finding is that some patients cannot fully dilate their microvasculature during exercise despite having a normal response to saline-induced hyperaemia. These patients exhibited impaired microvascular vasodilation leading to a delayed and insufficient Q increase during exercise. Unlike pharmacological hyperaemia, exercise involves a dynamic and integrated regulation of Q through neurohormonal, endothelial, and metabolic mechanisms, which may vary at an individual level. This impaired “natural” vasodilatory capacity, potentially masked when directly inducing instantaneous maximal artificial hyperaemia, may be a promising target for future translational research to better understand the in vivo mechanisms of CMD.

CMD has been previously dichotomised into “structural” and “functional” endotypes25. Exercise-based assessment offers a valuable perspective in distinguishing the mechanisms underlying low MRR. When hyperaemic Rμ is abnormally high, impaired MRR results from impaired microvascular vasodilatation. This so-called “structural” endotype can be related to anatomical structural microvascular rarefaction or reduced arteriolar lumen size but could also reflect inadequate functional vasodilation due to endothelial, autonomic, or humoral dysfunction1, making the “structural” terminology potentially misleading. Conversely, when hyperaemic Rμ remains normally low, impaired MRR is not due to impaired vasodilation but to a low resting microvascular tone with increased resting Q. Whether this so-called “functional” endotype constitutes a pathological state of the coronary microvasculature warrants further exploration. It remains unclear whether this resting state is related to an exaggerated adrenergic drive, impaired autoregulation, uncoupling of Q from cardiac work, or a high resting myocardial oxygen demand with a reduced myocardial efficiency5.

These findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating. While several MRR threshold values have been proposed in previous studies, a 2.3 threshold was chosen to enhance the specificity of our phenotypic CMD description3. Using this cutoff, all MRRsaline-defined CMD participants had a CFR <2.5. The reproducibility of exercise-derived data requires further investigation. However, measurements during exercise were performed with a stable distal blood temperature signal. To minimise variability in Rμ measurements, all assessments were conducted in the LAD, the most representative of the whole myocardial mass. FFR values were measured with the microcatheter positioned in the coronary artery, which may have caused a slight decrease in the hyperaemic distal coronary pressure/aortic pressure. However, this has a limited impact on the results’ interpretation, especially considering the non-obstructive nature of the studied vessels.

A standardised approach combining hyperaemic Rμ with MRR differentiates a low resting vascular tone from impaired vasodilation during exercise. The identification of an exercise-related CMD phenotype, characterised by impaired vasodilatory capacity during exercise despite a normal response to instantaneous artificial maximal hyperaemia, could offer a more granular assessment of microvascular function and may be a promising target for future research in ANOCA.

Central illustration. Assessment of coronary microvascular dysfunction endotypes using intracoronary continuous thermodilution coupled with exercise stress testing. A) Absolute microvascular resistance (Rμ) and coronary blood flow (Q) were measured in the LAD using continuous thermodilution. Saline was infused at 10 mL/min (rest) and 20 mL/min (hyperaemia) to assess MRRsaline. In addition, patients performed the cycling exercise using a supine cycling ergometer with an increasing workload of 30 watts every 2 minutes. During exercise, measurements were performed with a saline infusion rate of 10mL/min to assess peak exercise MRRexercise. B) A standardised approach combining hyperaemic Rµ with MRR differentiated four distinct phenotypes. C) Rμ and Q are represented according to the percentage of the theoretical workload achieved by participants. The white areas denote physical exercise, and the blue areas denote saline-induced hyperaemia. Participants with impaired MRRsaline and elevated hyperaemic Rµ ≥500 WU (red, n=7) had similar resting Rµ (1,286±410 WU vs 1,247±228 WU) and Q (84±25 mL/min vs 81±24 mL/min) compared to the normal MRR group but exhibited a smaller Rµ decrease (median 139 [interquartile range 64; 288] WU/30 watts vs 194 [95; 446] WU/30 watts) and Q increase (20 [10; 38] mL/min/30 watts vs 77 [51; 108] mL/min/30 watts) during exercise, suggesting normal resting tone but impaired hyperaemic vasodilatory capacity. Participants with impaired MRRsaline and normal hyperaemic Rµ <500 WU (green, n=4) had lower resting Rµ (671±219 WU vs 1,247±228 WU) and higher resting Q (152±39 mL/min vs 81±24 mL/min) compared to the normal MRR group but showed similar Rµ decrease (183 [96; 253] WU/30 watts vs 194 [95; 446] WU/30 watts) and Q increase (55 [21; 151] mL/min/30 watts vs 77 [51; 108] mL/min/30 watts) during exercise, suggesting a low resting tone but normal hyperaemic vasodilatory response. CFR: coronary flow reserve; FFR: fractional flow reserve; LAD: left anterior descending artery; MRR: microvascular resistance reserve; MRRexercise: MRR during exercise; MRRsaline: microvascular resistance reserve with saline infusion; Pa: aortic pressure; Pd: distal coronary pressure; WU: Wood units

Funding

Funding was provided by the ACTION Study Group.

Conflict of interest statement

M. Zeitouni has received research grants and honoraria from Bayer, BMS Pfizer, la Fédération Française de Cardiologie, Servier, AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, and Abbott. J. Silvain has received research grants and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare SAS, Abbott, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim France, CSL Behring SA, Gilead Sciences, and Sanofi-Aventis France; has been a stockholder of PharmaSeeds, Terumo France SAS, and Zoll. G. Montalescot has received research grants and honoraria from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Ascendia, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Celecor, CSL Behring, Idorsia, Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Opalia, Pfizer, Quantum Genomics, Sanofi, and Terumo. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.