Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: Few data are available on polymer-free drug-eluting stents in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Aims: We aimed to determine the efficacy and safety of a polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (AES), using a reservoir-based technology for drug delivery, compared with a biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting stent (EES).

Methods: This was a randomised, investigator-initiated, assessor-blind, non-inferiority trial conducted at 14 hospitals in Italy (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04135989). All-comer patients undergoing PCI were randomly assigned to either polymer-free AES or biodegradable-polymer EES. The primary endpoint was a device-oriented composite endpoint, including cardiovascular death, target vessel myocardial infarction, or target lesion revascularisation at 1-year follow-up.

Results: Between January 2020 and June 2022, a total of 2,107 patients with 3,042 coronary lesions were randomised to polymer-free AES (1,051 patients) or biodegradable-polymer EES (1,056 patients). At 1-year follow-up, the primary endpoint occurred in 86 (8.2%) patients randomised to polymer-free AES and 76 (7.2%) patients randomised to biodegradable-polymer EES (risk difference 1%, upper limit of the 1-sided 95% confidence interval [CI] of 2.9%; p for non-inferiority=0.041). There were no significant differences in the incidence of the components of the primary endpoint between groups. However, definite or probable stent thrombosis occurred more frequently in patients randomised to polymer-free stents (1.0% vs 0.3%; hazard ratio 3.72, 95% CI: 1.04-13.33; p=0.044) due to an increased risk of early stent thrombosis within 30 day

Conclusions: In all-comer patients undergoing PCI, polymer-free AES were non-inferior to biodegradable-polymer EES at 1-year follow-up in terms of a device-oriented composite endpoint despite being associated with an increased risk of early stent thrombosis.

New-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) have consistently outperformed bare metal stents and early-generation DES in terms of safety and efficacy and represent the standard of care in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1. Polymer-free DES are an additional iteration in stent technology that avoid the potential risks associated with chronic inflammatory responses to polymers and those related to polymer webbing, delamination, or cracking, which have been reported for both permanent and biodegradable polymers23. However, randomised data supporting the use of polymer-free DES for PCI remain limited, with trials yielding mixed results4567. The Cre8 EVO amphilimus-eluting stent (AES; Alvimedica) is a thin-strut, polymer-free, cobalt-chromium stent with reservoirs located on the outer surface releasing sirolimus formulated with a non-polymeric mixture of long-chain fatty acids. This structure allows for a controlled sirolimus elution with a release kinetic analogous to other contemporary DES. To date, the polymer-free AES has been tested against durable-polymer DES in moderately sized randomised trials or in specific populations, such as diabetic patients678. Hence, whether the use of this polymer-free DES in a broader, unselected patient population provides similar outcomes to other new-generation DES remains to be conclusively established.

Against this background, we designed the Personalized Vs. Standard Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy and New-generation Polymer-Free vs- Biodegradable-Polymer DES (PARTHENOPE) trial to evaluate the non-inferiority of polymer-free AES compared with biodegradable-polymer DES at 1-year follow-up in all-comers undergoing PCI.

Methods

Study design and patients

PARTHENOPE was an investigator-initiated, assessor-blind, multicentre, randomised trial, with few exclusion criteria, conducted at 14 hospitals in Italy (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04135989). The trial had a 2-by-2 factorial design with two independent hypotheses: (1) the non-inferiority of the polymer-free AES to the biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting stent (EES; SYNERGY Stent [Boston Scientific]) at 1-year follow-up and (2) the superiority of a personalised duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) compared with standard DAPT for 12 months at 2-year follow-up. The design of this study has been described previously8. A list of the investigators can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1. Herein, we report the results of the comparison between the two DES. The entire spectrum of coronary syndromes and lesions subsets were allowed, without limitations on the number of stents or lesions, or vessel to be treated. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Supplementary Appendix 2. The trial protocol was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University of Naples Federico II and the ethics committee of each participating centre. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the specifications of the International Conference of Harmonization, and the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent. Patients could also provide initial oral consent, but written informed consent was required within 72 hours after randomisation.

Randomisation and masking

After successful crossing of the first target lesion with a coronary guidewire, patients were randomly allocated to receive either the polymer-free AES or the biodegradable-polymer EES, along with either a personalised or standard DAPT strategy, with each participant having an equal probability of being assigned to 1 of the 4 treatment combinations. Web-based randomisation was done using a computer-generated sequence stratified by centre, with variable block sizes of 4 or 8. The sequence of block sizes was randomly generated to further enforce concealment. Patients and treating physicians were aware of group allocations.

Procedures

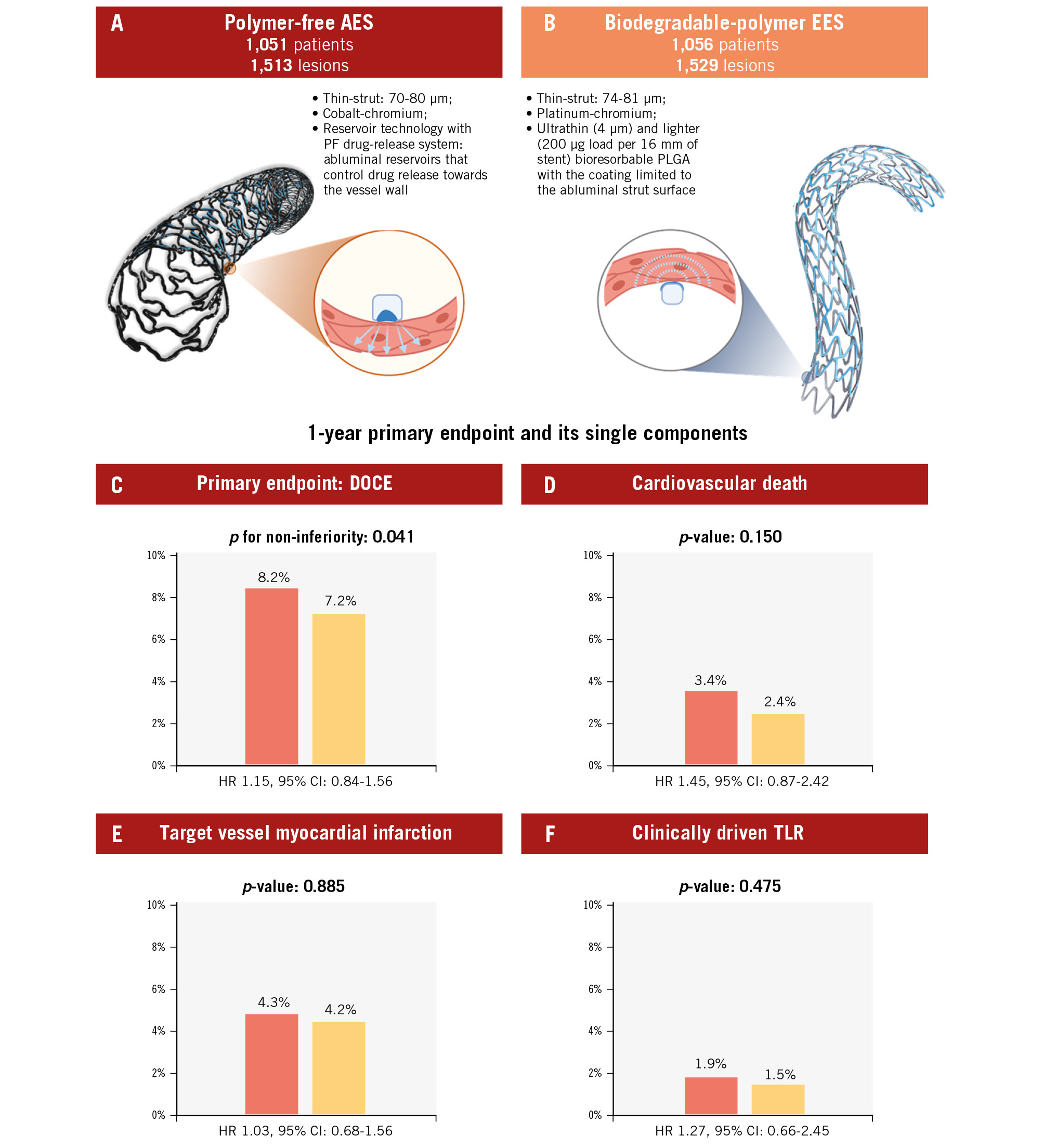

The Cre8 EVO stent is a thin-strut (70-80 μm), cobalt-chromium platform with a polymer-free design and a proprietary reservoir technology. The stent’s outer surface has reservoirs that control the release of the amphilimus compound, which is based on sirolimus and formulated with a non-polymeric mixture of long-chain fatty acid as a carrier. The Cre8 EVO stent has an ultrathin (<3 μm) and high-density carbon film. Approximately 50% of the drug is released at 18 days, while the elution is completed at 90 days9. The SYNERGY biodegradable-polymer EES is a thin-strut (74-81 μm) platinum-chromium metal alloy stent with an abluminal polymer (poly lactic-co-glycolic acid) that elutes everolimus (100 μg/cm2) within 90 days with a drug release kinetic similar to the Cre8 EVO stent10. Additional details on the devices used in the trial are reported in Supplementary Appendix 3.

Lesion preparation (predilation, direct stenting, and post-dilation), the dose of unfractionated heparin, and the use of intravenous antiplatelet agents were left to the discretion of the operators. A low dose of aspirin (75 to 162 mg daily) was administered throughout the trial. The choice of the P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) was left to the discretion of the treating physicians, although the trial protocol recommended clopidogrel (75 mg daily) in patients with chronic coronary syndrome and ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily) or prasugrel (10 mg daily, or 5 mg daily in patients weighing <60 kg or aged ≥75 years) in patients with acute coronary syndrome. DAPT duration in the trial was randomly assigned, and the DAPT score was used to stratify the ischaemic and bleeding risks (Supplementary Appendix 4)11. Patients randomised to personalised DAPT and at high bleeding risk (DAPT score <2) received DAPT for 3 or 6 months in case of chronic or acute coronary syndrome, respectively, whereas patients at high ischaemic risk (DAPT score ≥2) received DAPT for 24 months. Patients randomised to standard DAPT received DAPT for 12 months. Clinical follow-up was obtained at 3, 6, and 12 months by office visits or telephone interviews.

Endpoints

The prespecified primary endpoint was a device-oriented composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI) not clearly attributed to a non-target vessel, or clinically driven target lesion revascularisation within 1 year of the index procedure, as recommended by the Academic Research Consortium-2 criteria (ARC-2)12. MI was defined based on the fourth universal definition of MI13, and periprocedural MI was further adjudicated using the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) and ARC-2 criteria1214. Stent thrombosis was defined according to the ARC-2 criteria12. Additional secondary endpoints included any revascularisation, target vessel and target lesion revascularisation, and bleeding events. Endpoint definitions are reported in Supplementary Appendix 5. An independent clinical events committee blinded to treatment assignment adjudicated all study endpoints.

Statistical analysis

The study was designed to show non-inferiority of the Cre8 EVO AES versus the SYNERGY EES regarding the primary composite endpoint. Based on prior trials with a similar design, we assumed an event rate of 8% for the primary endpoint in the control group1516. Therefore, a total of 2,106 patients would provide 80% power to show non-inferiority with a margin of 3.0%, an upper 1-sided α of 0.05, and an attrition rate of 4%. The 1-sided p-value for non-inferiority was calculated from a Z-test comparing differences between groups with the margin of non-inferiority. A sensitivity post hoc analysis accounting for the competing risk of death (or non-cardiovascular death for endpoints including cardiovascular death) was also conducted. All analyses were done on an intention-to-treat basis, with all patients included in the analyses according to the allocated stent. In addition, per-protocol analyses were carried out by including patients that received the randomly allocated stents in all target lesions. Continuous variables are presented as means±standard deviations (SD), and categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentage). The cumulative event rates for the primary and secondary endpoints were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) from Cox regression analysis were used to compare differences in the primary and secondary endpoints. For the secondary endpoints, we prespecified the use of the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons8. However, both unadjusted and adjusted p-values are reported. The treatment effect of the Cre8 EVO AES versus the biodegradable-polymer EES was compared in the following prespecified subgroups: age, sex, diabetes, acute coronary syndrome, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), chronic kidney disease, complex PCI, small vessel disease, and DAPT strategy. All analyses were performed using R, version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

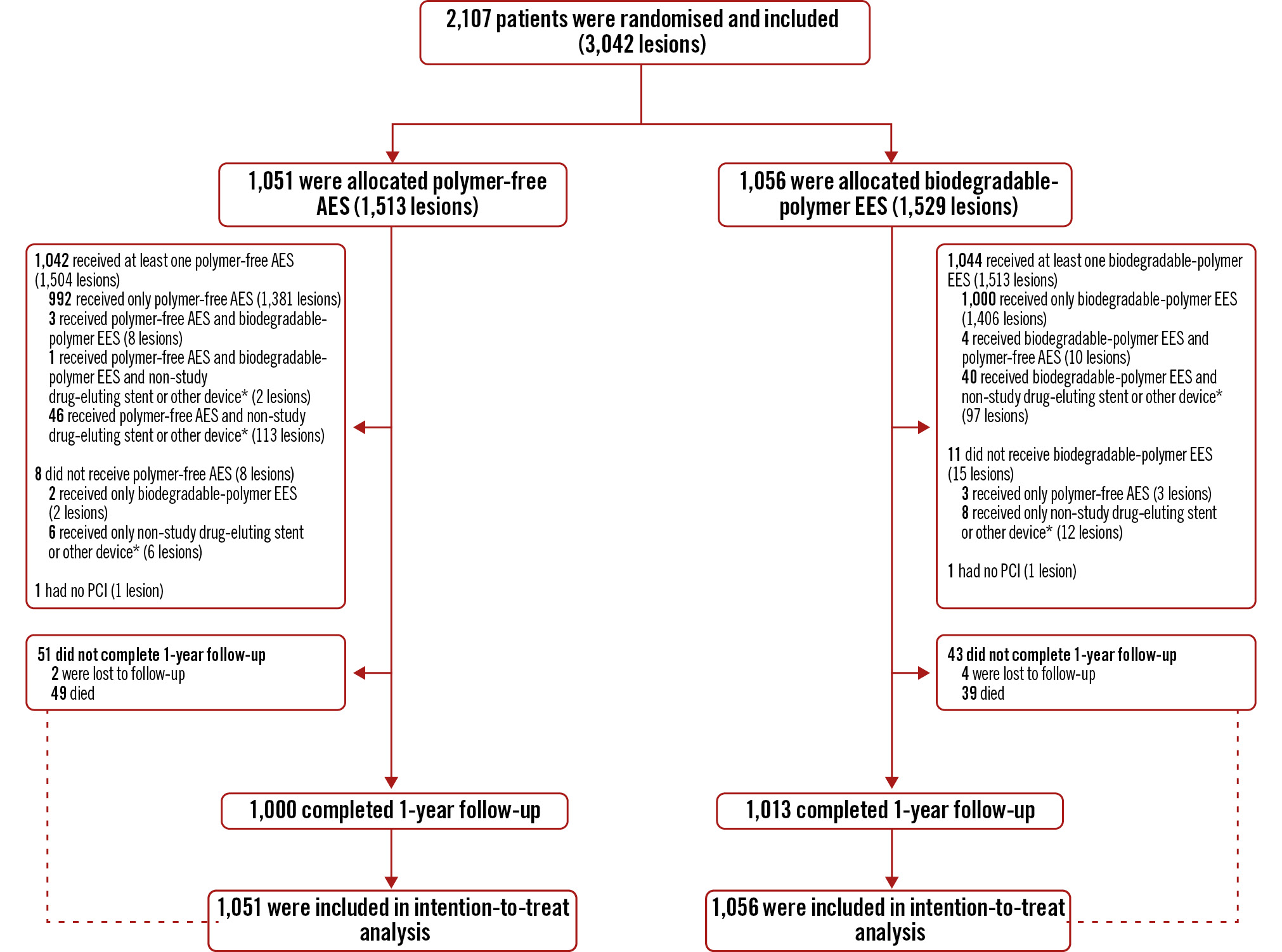

Between 22 January 2020 and 22 June 2022, we randomly assigned 2,107 patients with 3,042 target lesions to undergo PCI with the polymer-free AES (1,051 patients and 1,513 lesions) or the biodegradable-polymer EES (1,056 patients and 1,529 lesions) (Figure 1). A total of 2,013 (95.5%) patients completed 1-year follow-up, and 88 (4.2%) died; thus, follow-up data were available for 2,101 (99.7%) patients. Six (0.3%) patients were lost to follow-up (Figure 1). Participants were aged between 28 and 94 years (mean 63.9 [SD 10.6]), 465 (22.1%) were female, 658 (31.2%) had diabetes, and 1,607 (76.3%) presented with acute coronary syndrome (Table 1). A high proportion of patients had acute STEMI (776 [36.8%] of 2,107). In nearly all patients (2,086 [99.0%] of 2,107), at least one randomly assigned stent was implanted (Figure 1). Nineteen (0.9%) patients did not receive the allocated stent, and 2 (0.1%) patients did not undergo PCI (Figure 1). One quarter of the patients underwent complex PCI (527 [25.0%] of 2,107) (Table 2). The mean number of lesions treated per patient was 1.4 (SD 0.7), and 714 (33.9%) patients had more than one lesion treated; the mean total stent length per patient was 41 mm (SD 26.5). The mean total stent length per lesion was 29 mm (SD 15), and the mean stent diameter per lesion was 3 mm (SD 0.5). Almost all lesions were treated with stents (2,995 [98.4%] of 3,042). Direct stenting was performed in 1,145 (38.2%) of 2,995 stented lesions. Medications and antiplatelet therapy at baseline, discharge, and during follow-up did not differ between groups (Supplementary Table 1).

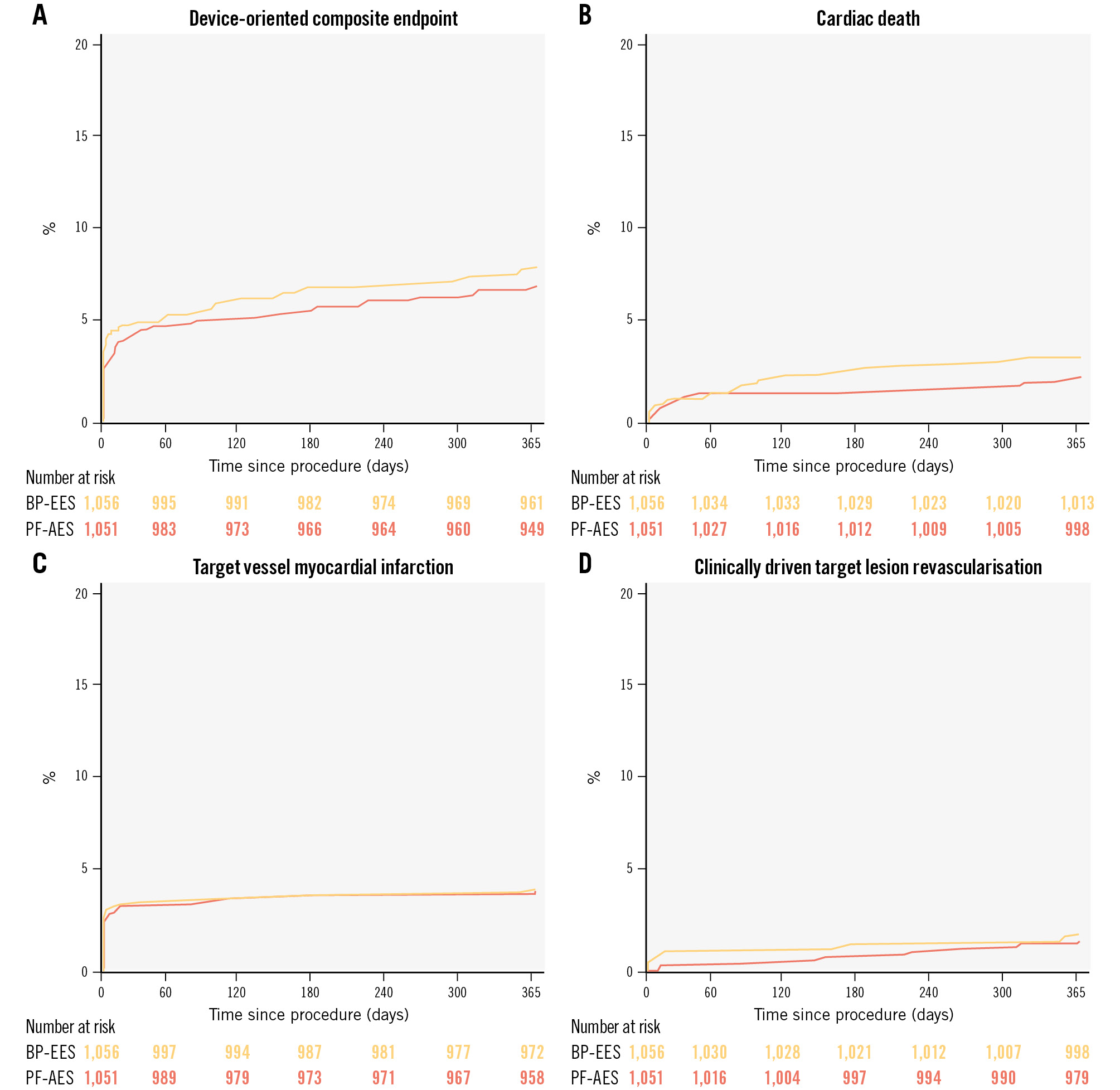

At 1-year follow-up, the primary endpoint had occurred in 86 (8.2%) patients randomised to the polymer-free AES group and in 76 (7.2%) patients randomised to the biodegradable-polymer EES group (Figure 2A, Table 3, Central illustration). Non-inferiority of the polymer-free AES compared with the biodegradable-polymer EES was established with an absolute risk difference of 1% (95% CI: −0.9% to 2.9%; p for non-inferiority=0.041). Superiority testing for the primary endpoint did not show significant differences between the polymer-free AES and the biodegradable-polymer EES (HR 1.15, 95% CI: 0.84-1.56; p=0.388). A per-protocol analysis yielded consistent results (absolute risk difference 0.6%; p for non-inferiority 0.019) (Supplementary Figure 1-Supplementary Figure 2-Supplementary Figure 3-Supplementary Figure 4, Supplementary Table 2). Cardiovascular death occurred in 36 (3.4%) patients randomised to the polymer-free AES and in 25 (2.4%) patients randomised to the biodegradable-polymer EES (HR 1.45, 95% CI: 0.87-2.42; p=0.150). This numerical increase was attributed to a higher number of undetermined deaths in the experimental arm. The complete adjudication of causes of death is provided in Supplementary Table 3. The risks of target vessel MI (4.3% vs 4.2%, HR 1.03, 95% CI: 0.68-1.56; p=0.885) and target lesion revascularisation (1.9% vs 1.5%, HR 1.27, 95% CI: 0.66-2.45; p=0.475) were similar between groups (Figure 2, Table 3). Definite or probable stent thrombosis occurred in 11 (1.0%) patients in the polymer-free AES group and 3 (0.3%) patients in the biodegradable-polymer EES group (HR 3.72, 95% CI: 1.04-13.33; p=0.044). This difference was not significant when adjusted for multiple comparisons (adjusted p=0.292). Definite stent thrombosis occurred in 11 (1.0%) patients in the polymer-free AES group and 2 (0.2%) in the biodegradable-polymer EES group (Table 3). Out of the 14 cases of definite or probable stent thrombosis, 4 occurred as acute events, 7 as subacute, and 3 as late (>30 days) occurrences. In 9 cases, stent thrombosis occurred in stents with a diameter less than 3 mm. A detailed description of stent thrombosis cases is provided in Supplementary Table 4. The frequencies of other secondary endpoints were similar in both study arms (Table 3).

A post hoc analysis accounting for the competing risk of death showed consistent results for the primary and secondary endpoints (Supplementary Table 5).

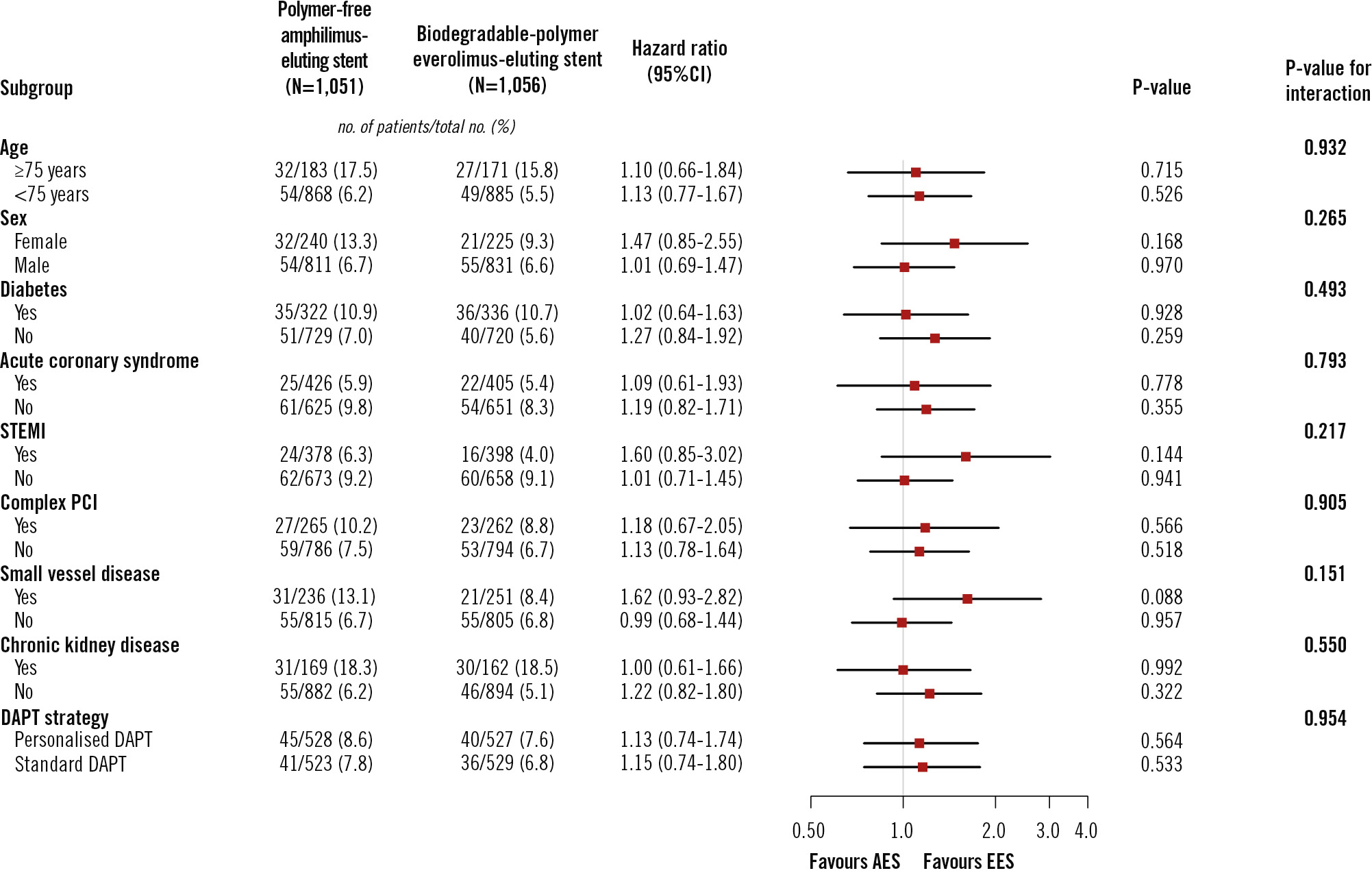

There was no heterogeneity in the treatment effect of polymer-free AES versus biodegradable-polymer EES across the stratified analyses for age, sex, diabetes, acute coronary syndrome, STEMI, chronic kidney disease, complex PCI, small vessel disease, or DAPT strategy. The results were consistent in the per-protocol population (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 5). Regarding the potential for heterogeneity introduced by different DAPT strategies, which could affect the study’s external validity, we analysed the heterogeneity of the treatment effect of polymer-free AES versus biodegradable-polymer EES on the primary endpoint across DAPT strategies. Consistency in risk estimates for the primary endpoint was observed in both the intention-to-treat (p-interaction=0.954) and per-protocol populations (p-interaction=0.901), across both personalised and standard DAPT strategies. Consequently, no significant interaction between the type of stent and the DAPT regimen was evident (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 1. Trial profile. *balloon angioplasty or drug-coated balloon. AES: amphilimus-eluting stent; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (N=1,051) | Biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting stent (N=1,056) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean | 63.8 (10.9) | 64 (10.4) |

| Male | 811/1,051 (77.2) | 831/1,056 (78.7) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean | 28 (4.7) | 28.2 (4.7) |

| Family history of CAD | 305/1,051 (29.0) | 309/1,056 (29.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 322/1,051 (30.6) | 336/1,056 (31.8) |

| Diabetes treatment | ||

| Diet | 47/322 (14.6) | 50/336 (14.9) |

| Oral treatment | 176/322 (54.7) | 190/336 (56.5) |

| Insulin therapy | 99/322 (30.7) | 96/336 (28.6) |

| Current smoker | 524/1,051 (49.9) | 526/1,056 (49.8) |

| Hypertension | 777/1,051 (73.9) | 799/1,056 (75.7) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 656/1,051 (62.4) | 660/1,056 (62.5) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 215/1,051 (20.5) | 204/1,056 (19.3) |

| Congestive heart failure | 76/1,051 (7.2) | 61/1,056 (5.8) |

| Previous PCI | 224/1,051 (21.3) | 230/1,056 (21.8) |

| Previous CABG | 36/1,051 (3.4) | 44/1,056 (4.2) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 83/1,051 (7.9) | 72/1,056 (6.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 169/1,051 (16.1) | 162/1,056 (15.3) |

| Prior stroke or TIA | 41/1,051 (3.9) | 30/1,056 (2.8) |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 140/1,051 (13.3) | 136/1,056 (12.9) |

| Indication for revascularisation | ||

| STEMI | 378/1,051 (36.0) | 398/1,056 (37.7) |

| NSTE-ACS | 426/1,051 (40.5) | 405/1,056 (38.4) |

| Chronic coronary syndrome | 247/1,051 (23.5) | 253/1,056 (23.7) |

| Anaemia | 258/1,051 (24.5) | 254/1,056 (24.1) |

| History of bleeding | 18/1,051 (1.7) | 12/1,056 (1.1) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean | 137.1 (22.9) | 137.6 (23.3) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean | 76 (12.9) | 76.7 (13.6) |

| Heart rate, bpm | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean | 74.2 (14) | 74.6 (14.6) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | ||

| N | 1,028 | 1,035 |

| Mean | 49.1 (8.8) | 49.2 (8.7) |

| DAPT score | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.4) |

| Baseline drugs | ||

| Unfractionated heparin total dose | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean, IU | 5,970 (1,998) | 5,978 (2,037) |

| Current medication | 825/1,051 (78.5) | 821/1,056 (77.7) |

| Aspirin | 462/825 (56.0) | 463/821 (56.4) |

| P2Y12 receptor inhibitor | ||

| Clopidogrel | 159/825 (19.3) | 153/821 (18.6) |

| Prasugrel | 2/825 (0.2) | 1/821 (0.1) |

| Ticagrelor | 32/825 (3.9) | 38/821 (4.6) |

| None | 632/825 (76.6) | 629/821 (76.6) |

| Beta blocker | 356/825 (43.2) | 362/821 (44.1) |

| Statin | 421/825 (51.0) | 443/821 (54.0) |

| Other lipid-lowering drug | 126/825 (15.3) | 142/821 (17.3) |

| ACE inhibitors or ATII antagonist | 499/825 (60.5) | 539/821 (65.7) |

| PPI | 409/825 (49.6) | 418/821 (50.9) |

| SGLT-2 inhibitor | 15/825 (1.8) | 25/821 (3.0) |

| Oral antidiabetic | 198/825 (24.0) | 224/821 (27.3) |

| Insulin | 100/825 (12.1) | 98/821 (11.9) |

| Data are n/N (%) or mean (SD). Chronic kidney disease was defined as kidney damage or glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months or more, irrespective of the cause. ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme; ATII: angiotensin II; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; IU: international units; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; SD: standard deviation; SGLT-2: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIA: transient ischaemic attack | ||

Table 2. Angiographic and procedural characteristics.

| Polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (1,051 patients) | Biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting stent (1,056 patients) | |

|---|---|---|

| Treated lesions, per patient | ||

| N | 1,051 | 1,056 |

| Mean | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) |

| 1 | 700 (66.6) | 693 (65.6) |

| 2 | 252 (24.0) | 269 (25.5) |

| ≥3 | 99 (9.4) | 94 (8.9) |

| Haemodynamic support, per patient | ||

| IABP | 3/1,051 (0.3) | 2/1,056 (0.2) |

| LVAD | 0/1,051 (0) | 0/1,056 (0) |

| Vasopressor | 2/1,051 (0.2) | 8/1,056 (0.8) |

| Impellaa | 5/1,051 (0.5) | 0/1,056 (0) |

| Others | 0/1,051 (0) | 1/1,056 (0.1) |

| None | 1041/1,051 (99.0) | 1,045/1,056 (99.0) |

| Small vessel disease, per patient | 236/1,051 (22.5) | 251/1,056 (23.8) |

| Complex PCI, per patient (≥1 criteria) | 265/1,051 (25.2) | 262/1,056 (24.8) |

| ≥3 coronary vessels treated | 99/1,051 (9.4) | 94/1,056 (8.9) |

| ≥3 stents implanted | 192/1,051 (18.3) | 218/1,056 (20.6) |

| ≥3 lesions treated | 99/1,051 (9.4) | 94/1,056 (8.9) |

| Bifurcation with 2 stents implanted | 29/1,051 (2.8) | 31/1,056 (2.9) |

| Total stent length ≥60 mm | 202/1,051 (19.2) | 222/1,056 (21.0) |

| Treatment of chronic total occlusion | 11/1,051 (1.0) | 12/1,056 (1.1) |

| Number of lesions | 1,513 | 1,529 |

| Target vessel location, per lesion | ||

| Left main artery | 20/1,513 (1.3) | 37/1,529 (2.4) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 700/1,513 (46.3) | 682/1,529 (44.6) |

| Left circumflex artery | 347/1,513 (22.9) | 357/1,529 (23.3) |

| Right coronary artery | 446/1,513 (29.5) | 453/1,529 (29.6) |

| Bypass graft | 3/1,513 (0.2) | 5/1,529 (0.3) |

| Saphenous vein graft | 2/3 (66.7) | 4/5 (80.0) |

| Arterial graft | 1/3 (33.3) | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Restenotic lesion | 66/1,513 (4.4) | 80/1,529 (5.2) |

| Total occlusion | 254/1,513 (16.8) | 228/1,529 (14.9) |

| Evidence of thrombus | 424/1,513 (28.0) | 422/1,529 (27.6) |

| Thrombus aspiration | 38/1,513 (2.5) | 40/1,529 (2.6) |

| Treatment of bifurcation lesion | 151/1,513 (10.0) | 133/1,529 (8.7) |

| TIMI flow pre-PCI, per lesion | ||

| 0 or 1 | 337/1,513 (22.3) | 315/1,529 (20.6) |

| 2 | 189/1,513 (12.5) | 173/1,529 (11.3) |

| 3 | 987/1,513 (65.2) | 1,041/1,529 (68.1) |

| TIMI flow post-PCI, per lesion | ||

| 0 or 1 | 3/1,513 (0.2) | 7/1,529 (0.5) |

| 2 | 22/1,513 (1.5) | 19/1,529 (1.2) |

| 3 | 1,488/1,513 (98.3) | 1,503/1,529 (98.3) |

| Type of intervention, per lesion | ||

| Stent implantation | 1,485/1,512 (98.2) | 1,510/1,528 (98.8) |

| Balloon dilation only | 27/1,512 (1.8) | 18/1,528 (1.2) |

| Direct stenting | 555/1,485 (37.4) | 590/1,510 (39.1) |

| Post-dilation | 920/1,485 (62.0) | 865/1,510 (57.3) |

| Number of stents, per lesion | ||

| N | 1,485 | 1,510 |

| Mean | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.6) |

| 1 | 1,204/1,485 (81.1) | 1,157/1,510 (76.6) |

| 2 | 236/1,485 (15.9) | 298/1,510 (19.7) |

| 3 | 40/1,485 (2.7) | 45/1,510 (3.0) |

| 4 | 5/1,485 (0.3) | 9/1,510 (0.6) |

| 5 | 0/1,485 (0) | 1/1,510 (0.1) |

| 6 | 0/1,485 (0) | 0/1,510 (0) |

| Overlapping stents, per lesion | 250/281 (89.0) | 320/353 (90.7) |

| Number of stents | 1,816 | 1,929 |

| Type of stent, per lesion | ||

| Study stent polymer-free AES | 1,760/1,816 (96.9) | 11/1,929 (0.6) |

| Study stent biodegradable-polymer EES | 9/1,816 (0.5) | 1,867/1,929 (96.8) |

| Other drug-eluting stents | 47/1,816 (2.6) | 51/1,929 (2.6) |

| Total stent length per lesion, mm | ||

| N | 1,485 | 1,510 |

| Mean | 29.1 (14.9) | 29.1 (14.7) |

| Mean stent diameter per lesion, mm | ||

| N | 1,485 | 1,510 |

| Mean | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) |

| Maximum stent diameter per lesion, mm | ||

| N | 1,485 | 1,510 |

| Mean | 3 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) |

| Data are mean (SD), n (%) or n/N (%). aBy Abiomed. AES: amphilimus-eluting stent; CTO: chronic total occlusion; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; LVAD: left ventricular assist device; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction | ||

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves at 1-year follow-up. Device-oriented composite endpoint (A), cardiac death (B), target vessel myocardial infarction (C), and clinically driven target lesion revascularisation (D). BP-EES: biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting stent (orange); PF-AES: polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (red).

Table 3. Outcomes at 1-year follow-up.

| Polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (N=1,051) | Biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting stent (N=1,056) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint (device-oriented composite endpoint) | 86 (8.2) | 76 (7.2) | 1.15 (0.84-1.56) | 0.388 |

| Cardiovascular death | 36 (3.4) | 25 (2.4) | 1.45 (0.87-2.42) | 0.150 |

Target vessel myocardialinfarction |

45 (4.3) | 44 (4.2) | 1.03 (0.68-1.56) | 0.885 |

| Clinically driven target lesion revascularisation | 20 (1.9) | 16 (1.5) | 1.27 (0.66-2.45) | 0.475 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| All-cause death | 49 (4.7) | 39 (3.7) | 1.27 (0.83-1.93) | 0.266 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 50 (4.8) | 48 (4.5) | 1.05 (0.71-1.56) | 0.807 |

| Periprocedural myocardial infarction | ||||

Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction |

36 (3.4) | 35 (3.3) | 1.04 (0.65-1.65) | 0.883 |

| ARC-2 | 22 (2.1) | 14 (1.3) | 1.59 (0.81-3.1) | 0.177 |

| SCAI hierarchicala | 20 (1.9) | 12 (1.1) | 1.68 (0.82-3.45) | 0.153 |

| SCAI non-hierarchicalb | 34 (3.2) | 25 (2.4) | 1.37 (0.82-2.3) | 0.227 |

| Cardiovascular death or myocardial infarction | 81 (7.7) | 70 (6.6) | 1.17 (0.85-1.61) | 0.339 |

| Any revascularisation | 34 (3.2) | 34 (3.2) | 1.02 (0.63-1.63) | 0.949 |

Any clinically driven revascularisation |

32 (3.0) | 32 (3.0) | 1.02 (0.62-1.66) | 0.949 |

| Any target vessel revascularisation | 21 (2.0) | 21 (2.0) | 1.02 (0.55-1.86) | 0.961 |

Clinically driven target vessel revascularisation |

20 (1.9) | 20 (1.9) | 1.02 (0.55-1.89) | 0.962 |

| Any target lesion revascularisation | 20 (1.9) | 17 (1.6) | 1.2 (0.63-2.28) | 0.588 |

| Definite or probable stent thrombosis | 11 (1.0) | 3 (0.3) | 3.72 (1.04-13.33) | 0.044c |

Early definite or probable stent thrombosis |

9 (0.9) | 2 (0.2) | 4.55 (0.98-21.07) | 0.053c |

| Late definite or probable stent thrombosis | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 2.03 (0.18-22.39) | 0.563 |

| Definite stent thrombosis | 11 (1.0) | 2 (0.2) | 5.58 (1.24-25.16) | 0.025c |

| Early definite stent thrombosis | 9 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) | 9.1 (1.15-71.83) | 0.036c |

| Late definite stent thrombosis | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 2.03 (0.18-22.39) | 0.563 |

| Cerebrovascular event | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | 1.21 (0.37-3.96) | 0.756 |

| Target vessel failure | 86 (8.2) | 79 (7.5) | 1.1 (0.81-1.49) | 0.538 |

| Any BARC bleeding | 157 (14.9) | 155 (14.7) | 1.03 (0.82-1.28) | 0.808 |

| BARC type 2 to 5 | 83 (7.9) | 86 (8.1) | 0.98 (0.72-1.32) | 0.872 |

| Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Percentages are cumulative incidence estimates. aIn the hierarchical approach, CK-MB is used as the leading biomarker for adjudication, whereas cardiac troponin is used only if CK-MB is missing. bIn the non-hierarchical approach, adjudication of either CK-MB or cardiac troponin need to fulfil the definition’s criteria (Supplementary Appendix 5). cP-values not significant (all p-values=0.292) after adjustment for multiple testing (Benjamini-Hochberg procedure). ARC-2: Academic Research Consortium-2; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI: confidence interval; CK-MB: creatine kinase-myocardial band; HR: hazard ratio; MI: myocardial infarction; SCAI: Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions | ||||

Central illustration. One-year results of the PARTHENOPE trial. Trial design with the main characteristics of the two study devices (A, B). The polymer-free AES (red) was non-inferior when compared to the biodegradable-polymer EES (orange). Non-inferiority testing for the primary endpoint (C) and superiority testing for the individual components of the primary endpoint (D, E, F) did not show significant differences between the polymer-free AES and the biodegradable-polymer EES. AES: amphilimus-eluting stent; CI: confidence interval; DOCE: device-oriented composite endpoint; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; HR: hazard ratio; PF: polymer-free; PLGA: poly lactic-co-glycolic acid; TLR: target lesion revascularisation

Figure 3. Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome in the intention-to-treat population. Chronic kidney disease was defined as kidney damage or glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months or more, irrespective of the cause. Complex PCI was defined as one of the following characteristics: ≥3 coronary vessels treated, ≥3 stents implanted, ≥3 lesions treated, bifurcation with 2 stents implanted, total stent length ≥60 mm, or treatment of chronic total occlusion. Small vessel disease was defined as the implantation of stent(s) <3 mm in diameter in the target lesion(s). AES: amphilimus-eluting stent; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Discussion

In this randomised trial involving an all-comer cohort undergoing PCI, we found that polymer-free AES were non-inferior to biodegradable-polymer EES in terms of a device-oriented primary endpoint at 1-year follow-up. The trial included a broad patient population, with over 75% of the participants receiving treatment for acute coronary syndrome, including 37% with acute STEMI, which likely represents the highest proportion among similar all-comer stent trials. The broad age spectrum of participants, ranging from 28 to 94 years, reflects the inclusive nature of the enrolment and the diversity of contemporary clinical practice.

The Cre8 EVO AES has thus far only been evaluated in an all-comers setting in one trial5, which, compared with our study, enrolled a smaller cohort of patients (1,491 vs 2,107 patients), included more patients with chronic coronary syndrome (58% vs 25%), and recruited fewer patients with diabetes (20% vs 31%). It is noteworthy that the observed 4.2% rate of all-cause death at 1 year was somewhat higher than that reported by other all-comer trials, such as the LEADERS, RESOLUTE, COMPARE-II, BIOSCIENCE, BIO-RESORT, BIONYX, and SORT OUT IX trials, in which the rates of all-cause death ranged from 1.6% to 3.3%15161718192021. This suggests the potential inclusion of higher-risk patients by the current study.

A potential drawback of polymer-free technologies is the rapid release of the antiproliferative agent, often accompanied by a decline in efficacy22. Initial studies on polymer-free DES indicated that their antirestenotic performance, measured using late loss, was inferior to that of durable- or biodegradable-polymer DES23. In line with this, the SORT OUT IX trial found a 3-fold higher risk of target lesion revascularisation with the polymer-free biolimus-eluting stent (BioFreedom [Biosensors]), which releases approximately 90% of biolimus within the first 48 hours after implantation24. Although the stainless steel platform of the BioFreedom stent was thought to be linked to neointimal hyperplasia, a randomised trial, comparing the same BioFreedom stent with a stainless steel (112-120 μm) or a cobalt-chromium platform (84-88 μm), revealed a similar late loss for both devices25. This suggests that the overly rapid release of the drug, rather than the type of metallic platform, is probably responsible for the insufficient suppression of neointimal hyperplasia in this polymer-free DES. Two other polymer-free DES are available, and these control drug release in the absence of the polymer by combining sirolimus with probucol in the VIVO ISAR (Translumina) and Coroflex ISAR stents (B. Braun). Similarly to amphilimus, probucol is lipophilic and enables longer and more controlled drug elution. The efficacy of the probucol-based, polymer-free DES has been reported up to 10-year follow-up in the ISAR-TEST-5 trial4. Our trial, which is the largest to date to have investigated the Cre8 EVO AES, found very low rates of target lesion revascularisation at 1-year follow-up. These efficacy findings are well aligned with the ReCre8 and SUGAR trials, which showed a similar risk of target lesion revascularisation with the polymer-free AES compared with the durable-polymer zotarolimus-eluting stents in 1,491 all-comers and 1,175 diabetic patients, respectively56. In the SUGAR trial, the Cre8 EVO AES was shown to be non-inferior and superior to the Resolute Onyx zotarolimus-eluting device (Medtronic) regarding target lesion failure at 1 year, with the difference largely driven by reductions in target vessel MI and target lesion revascularisation6. However, in our trial, the rates of target vessel MI (4.3% vs 4.2%, HR 1.03) and clinically driven target lesion revascularisation (1.9% vs 1.5%, HR 1.27) did not differ between the AES and EES groups. Moreover, there was no heterogeneity in the treatment effect between the two randomly assigned devices with respect to the primary endpoint according to the presence or absence of diabetes. In terms of safety, we found a higher incidence of definite or probable stent thrombosis in patients undergoing polymer-free AES implantation compared with biodegradable-polymer EES implantation (1.0% vs 0.3%). This risk difference was notable in the first 30 days after PCI. Definite stent thrombosis accounted for 13 cases, whereas the only case of probable stent thrombosis occurred in a patient who died suddenly at home 19 days after revascularisation for a non-STEMI. In 2 cases occurring at days 4 and 13 after treatment with the Cre8 EVO, patients disrupted the two antiplatelet agents and the P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, respectively. Only 1 patient with stent thrombosis died; this occurred at 358 days due to a non-cardiac cause. It is worth noting that a potential signal of increased risk of early stent thrombosis was already observed in the ReCre8 trial, with 7 cases reported in patients randomised to polymer-free AES versus 2 cases in those receiving zotarolimus-eluting stents. However, when considering all cases of definite or probable stent thrombosis, this difference narrowed to 9 vs 6 cases, respectively5. Data from the largest meta-analysis comparing new-generation DES with bare-metal stents, among more than 25,000 patients, indicated a rate of definite stent thrombosis of 0.6% at 1-year follow-up. In more recent head-to-head trials comparing new-generation DES, the observed rates of definite stent thrombosis at 1 year ranged from 0.1% to ≤1%181920212627, although in the ONYX One trial, definite or probable stent thrombosis exceeded 1% at 1-year follow-up28. Taken together, these data suggest that although stent thrombosis remains infrequent in absolute terms, the overall rate might be higher with the Cre8 EVO AES than with other contemporary DES. Notably, thrombosed polymer-free AES stents were more frequently smaller in diameter and longer in length, characteristics that have been consistently associated with stent thrombosis293031.

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted in view of several limitations. Although the trial established the non-inferiority between the two devices, non-inferiority should be interpreted within the confines of the pre-established margin and the proximity of the upper limit of the 1-sided 95% CI of 2.9% to the non-inferiority threshold of 3.0%. Our trial protocol did not mandate the use of a screening log; as a result, we are unable to provide information on the number of patients assessed for eligibility but not included. Moreover, measurement of baseline and postprocedural cardiac biomarkers were highly recommended but not mandatory, and this could have influenced the rates of periprocedural MIs. The observed higher incidence of early stent thrombosis among patients randomised to the Cre8 EVO AES warrants further investigation. When p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, the p-value for stent thrombosis did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, while this finding could potentially be a false positive result, the increased risk still represents a potential safety concern that requires attention. Our findings cannot be extrapolated to other polymer-free DES. There may be several interrelated elements, including the drug release kinetic, the metallic platform, and the drug penetration into the coronary vessel, that collectively influence the overall efficacy and safety of the device. Finally, as with other all-comers stent trials, a further limitation is the open-label design whereby patients and treating physicians were not masked to treatment allocation. However, the members of the clinical events committee were unaware of the randomised arm.

Conclusions

Among all-comer patients undergoing PCI, the use of polymer-free AES in patients was non-inferior to biodegradable-polymer EES in terms of a device-oriented composite endpoint at 1-year follow-up. While the efficacy between the two devices was comparable, there was an increased risk of stent thrombosis within 30 days among patients who received the polymer-free DES, and this warrants further investigation.

Impact on daily practice

The use of polymer-free stents in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention has the potential to eliminate any risk associated with biodegradable or permanent polymers, which are currently used in coronary devices to control the release of the antiproliferative drug. In patients treated with polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stents, device-related outcomes were similar to those treated with biodegradable-polymer everolimus-eluting stents at 1-year follow-up. Although the antirestenotic properties of polymer-free stents have been questioned, the use of an amphilimus-eluting stent was associated with an excellent efficacy profile in comparison to biodegradable stents. The small excess of stent thrombosis within 30 days after amphilimus-eluting stent implantation requires additional studies.

Guest Editor

This paper was guest edited by Franz-Josef Neumann, MD, PhD; Department of Cardiology and Angiology, University Heart Center Freiburg - Bad Krozingen, Bad Krozingen, Germany.

Acknowledgements

This paper was guest edited by Franz-Josef Neumann, MD, PhD; Department of Cardiology and Angiology, University Heart Center Freiburg - Bad Krozingen, Bad Krozingen, Germany.

Funding

The trial was an investigator-initiated study supported by the Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences at the University of Naples “Federico II” with no external funding.

Conflict of interest statement

R. Piccolo reports personal fees from Biotronik, Amarin, Abiomed, and Medtronic, outside the submitted work. A. Chieffo reports speaker and/or consultation fees from Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Biosensors, Menarini, Medtronic, and Shockwave Medical, outside the submitted work. G. Tarantini reports lecture fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Abiomed, outside the submitted work. S. Leonardi reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca; and has received personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer, Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb, ICON, Chiesi, and Novo Nordisk, outside the submitted work. S. Biscaglia reports grant/contract from Eukon, GE HealthCare, Insight Lifetech, Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Sahajanand Medical Technologies Ltd., and Siemens, outside the submitted work. F. Costa reports personal fees from Chiesi Farmaceutici and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. F. Simonetti and D. Angellotti received a research grant from the CardioPath programme at Federico II University of Naples, Italy. E. McFadden reports personal fees and consultancy fees from Abbott and Biosensors, outside the submitted work. D. Capodanno reports speaker or consulting fees from Amgen, Arena, Chiesi, Daiichi Sankyo, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Terumo; and institutional fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work. G. Esposito reports personal fees from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Edwards Lifesciences, Novartis, Amarin, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work; and research grants to the institution from Alvimedica, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The Guest Editor reports consultancy fees from Novartis and Meril Life Sciences; speaker honoraria from Boston Scientific, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo and Meril Life Sciences; reports speaker honoraria paid to his institution from BMS/Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Boston Scientific, Siemens, and Amgen; and research grants paid to his institution from Boston Scientific and Abbott.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.