Abstract

BACKGROUND: Transfemoral access is often used when large-bore guide catheters are required for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of complex coronary lesions, especially when large-bore transradial access is contraindicated. Whether the risk of access site complications for these procedures may be reduced by ultrasound-guided puncture is unclear.

AIMS: We aimed to show the superiority of ultrasound-guided femoral puncture compared to fluoroscopy-guided access in large-bore complex PCI with regard to access site-related Bleeding Academic Research Consortium 2, 3 or 5 bleeding and/or vascular complications requiring intervention during hospitalisation.

METHODS: The ULTRACOLOR Trial is an international, multicentre, randomised controlled trial investigating whether ultrasound-guided large-bore femoral access reduces clinically relevant access site complications compared to fluoroscopy-guided large-bore femoral access in PCI of complex coronary lesions.

RESULTS: A total of 544 patients undergoing complex PCI mandating large-bore (≥7 Fr) transfemoral access were randomised at 10 European centres (median age 71; 76% male). Of these patients, 68% required PCI of a chronic total occlusion. The primary endpoint was met in 18.9% of PCI with fluoroscopy-guided access and 15.7% of PCI with ultrasound-guided access (p=0.32). First-pass puncture success was 92% for ultrasound-guided access versus 85% for fluoroscopy-guided access (p=0.02). The median time in the catheterisation laboratory was 102 minutes versus 105 minutes (p=0.43), and the major adverse cardiovascular event rate at 1 month was 4.1% for fluoroscopy-guided access and 2.6% for ultrasound-guided access (p=0.32).

CONCLUSIONS: As compared to fluoroscopy-guided access, the routine use of ultrasound-guided access for large-bore transfemoral complex PCI did not significantly reduce clinically relevant bleeding or vascular access site complications. A significantly higher first-pass puncture success rate was demonstrated for ultrasound-guided access. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04837404

During complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), large-bore (7 or 8 Fr) guide catheters are often preferred. They provide improved backup support and better compatibility with the equipment necessary to treat complex lesions, including heavily calcified lesions, left main lesions, complex bifurcations and chronic total occlusions (CTOs)12. As compared to transfemoral access (TFA), recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility and increased safety of large-bore transradial access (TRA) for complex PCI34. However, contraindications for large-bore TRA are not uncommon, including the presence of a small radial artery, known severe spasm, or anatomical variants. In these cases, large-bore TFA is needed. Previous studies have shown a high risk of clinically relevant bleeding or vascular complications when large-bore TFA is applied for complex PCI56. Routine use of ultrasound-guided puncture has been shown to lower the risk of a suboptimal puncture height as well as the risk of puncture in a calcified plaque, which are both associated with higher complication rates and failure of vascular closure devices (VCDs)78910. However, ultrasound-guided puncture of the femoral artery in coronary procedures, even in large-bore access for complex PCI, is not routinely applied, likely owing to the lack of robust evidence. In the recent Routine Ultrasound Guidance for Vascular Access for Cardiac Procedures (UNIVERSAL) randomised clinical trial, the use of ultrasound-guided femoral access did not significantly reduce bleeding or vascular complications, when compared to standard (fluoroscopy-guided) access11. Of note, the proportion of complex PCI in this trial was low, and 6 Fr access was mainly used. Whether ultrasound guidance has a potentially greater benefit on access site complications in a patient population undergoing transfemoral PCI with large-bore guide catheters (≥7 Fr) remains unknown.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND OBJECTIVES

The Ultrasound Guided Transfemoral Complex Large-bore PCI Trial (ULTRACOLOR) was an investigator-initiated, international, multicentre study with a prospective, open-label randomised controlled superiority design. Full study rationale, protocol and participating centres have been published previously12.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate whether the use of ultrasound guidance for TFA with large-bore guide catheters for complex PCI reduces clinically relevant access site-related bleeding or vascular complications.

As secondary objectives, ultrasound-guided and fluoroscopy-guided TFA were compared with regard to procedural duration, first-pass puncture rate, the incidence of accidental venous puncture and VCD failure. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at discharge and at 1-month follow-up were compared between both randomised groups. Clinically relevant complications of the additional access site (if applicable) were also studied.

TRIAL ORGANISATION

The trial was approved by the appropriate ethics review board at each site. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrolment. The trial was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All data were collected in an electronic data capturing system (eDREAM [Diagram B.V.]). Diagram B.V. was responsible for overall trial and data management, as well as the monitoring of the study. The evaluation of serious adverse events was performed by an independent data safety monitoring board (DSMB). A clinical events committee (CEC) reviewed and adjudicated all endpoint-related adverse events and was blinded to the randomised strategy (see Supplementary Appendix 1 for the CEC composition and charter). ULTRACOLOR follows the CONSORT guidelines (Supplementary Appendix 2) and has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04837404.

SITE SELECTION

All participating centres and operators were selected based on their experience with complex PCI and ultrasound-guided puncture. Every potential site had to fill in a questionnaire about the number and type of complex PCIs performed yearly, the preferred sheath size for complex PCI, and whether ultrasound-guided puncture in complex PCI was already standard of care. Furthermore, a detailed step-by-step approach for both access site strategies was provided in the previously published study design paper12. All participating operators received these instructions either by onsite training or by using a prerecorded training video.

INCLUSION

Patients of 18 years or older presenting with chronic coronary syndrome, unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and scheduled for PCI of complex coronary lesions, including CTO, left main stem, heavily calcified lesions and complex bifurcations, in whom the operator anticipated the need for at least one 7 Fr guide catheter for TFA, were screened for inclusion. Full definitions of complex coronary lesions have been published previously12. Patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or cardiogenic shock were excluded. Patients with contraindications for large-bore femoral access, such as occlusive peripheral artery disease, were also excluded.

RANDOMISATION

After providing written informed consent, eligible subjects were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive one of the two study treatments. Treatment assignments were performed centrally through a dedicated website in random permuted blocks with stratification by site. There was no blinding of the randomisation assignment.

STUDY GROUP DEFINITION

Femoral access was performed according to the randomised strategy.

ULTRASOUND-GUIDED ACCESS GROUP

The course of the femoral artery was first identified by palpation. Additional use of fluoroscopy to identify the femoral head was optional but recommended. Under direct visualisation with ultrasound, local anaesthetics were administered subcutaneously, and a subsequent puncture was performed. The use of micropuncture was optional and according to operators’ experience and preference.

FLUOROSCOPY-GUIDED ACCESS GROUP (COMPARATOR)

The course of the femoral artery was first identified by palpation, and additional fluoroscopy was performed to identify the ideal site for local anaesthetics administration and femoral artery puncture. The use of micropuncture was optional and according to operators’ experience and preference.

ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint was defined as clinically relevant access site-related bleeding or vascular complication requiring intervention of the randomised access site during hospitalisation. Bleeding was classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria and considered clinically relevant when the score was 2, 3 or 513. All bleeding, vascular complications and MACE were adjudicated by the CEC. The CEC was blinded to the randomisation group. The severity of bleeding/complication and type of intervention for vascular complications were specified in the CEC manual (Supplementary Appendix 1).

Secondary safety and efficacy endpoints were as follows (see also Supplementary Appendix 3 for definitions):

– BARC 2, 3 or 5 access site-related bleeding or vascular complication requiring intervention at the primary femoral access site at 30-day follow-up</p>

– BARC 2, 3 or 5 access site-related bleeding or vascular complication requiring intervention at the secondary femoral or radial access site (at discharge and at 30-day follow-up)

– MACE (at discharge and at 30-day follow-up)

– Vascular complication not requiring intervention at the primary femoral access site (at discharge and at 30-day follow-up)

– Vascular complication not requiring intervention at the secondary femoral or radial access site (at discharge and at 30-day follow-up)

– Procedural duration

– Time to access

– First-pass puncture rate

– Number of access attempt

− Accidental venepuncture rate

– Crossover (fluoroscopy-guided to ultrasound-guided or vice versa)

– Suboptimal femoral artery puncture, based on the ilioÂfemoral angiogram12

– Extremity pain (measured by the numeric rating scale [NRS]) directly after the procedure, at discharge, and at 30-day follow-up</p>

PROCEDURE, HAEMOSTASIS AND CLINICAL COURSE

The PCI strategy and choice of materials were left to the discretion of the operator. An iliofemoral angiogram was mandated before VCD placement to check for complications and to score the access height. Haemostasis was achieved, according to the local protocol, using a VCD unless contraindicated; in case of the latter, manual compression with a bandage was applied for haemostasis. Failure of VCDs was documented. The pain score related to the primary femoral access site directly after haemostasis was collected according to the NRS. Before discharge, all access sites were checked for potential complications including haematoma (haematoma size was documented). An additional ultrasound was performed within 1 month in case of suspected femoral artery occlusion or other vascular complications of the (additional) femoral or radial artery.

FOLLOW-UP

Follow-up was performed 30 days after index procedure discharge either by a phone call or an outpatient clinic visit. Any MACE, access site bleeding or vascular complications were documented. Adverse events (AE) were monitored from inclusion to 30-day follow-up and assessed by an independent DSMB, composed of two experienced cardiologists and one statistician, who reviewed patient safety and study integrity (see Supplementary Appendix 4 for the composition and reports of the DSMB).

SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATION AND STATISTICS

The appropriate sample size was estimated at 542 subjects (271 subjects in each group), based on a type 1 error rate of 5% and a power of 80%, assuming a 16% complication rate in the comparator group and a 49% reduction (7.84% complication rate) in the ultrasound-guided group314. An intention-to-treat analysis was used for the primary analysis and included all randomised patients. Statistical analysis was performed according to a predefined statistical analysis plan (Supplementary Appendix 5) by an independent statistician using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Predefined subgroup analyses were performed including several potential differing treatment effects for several high-risk subgroups. A detailed specification of the subgroups can be found in the statistical analysis plan (Supplementary Appendix 5).

Results

STUDY POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

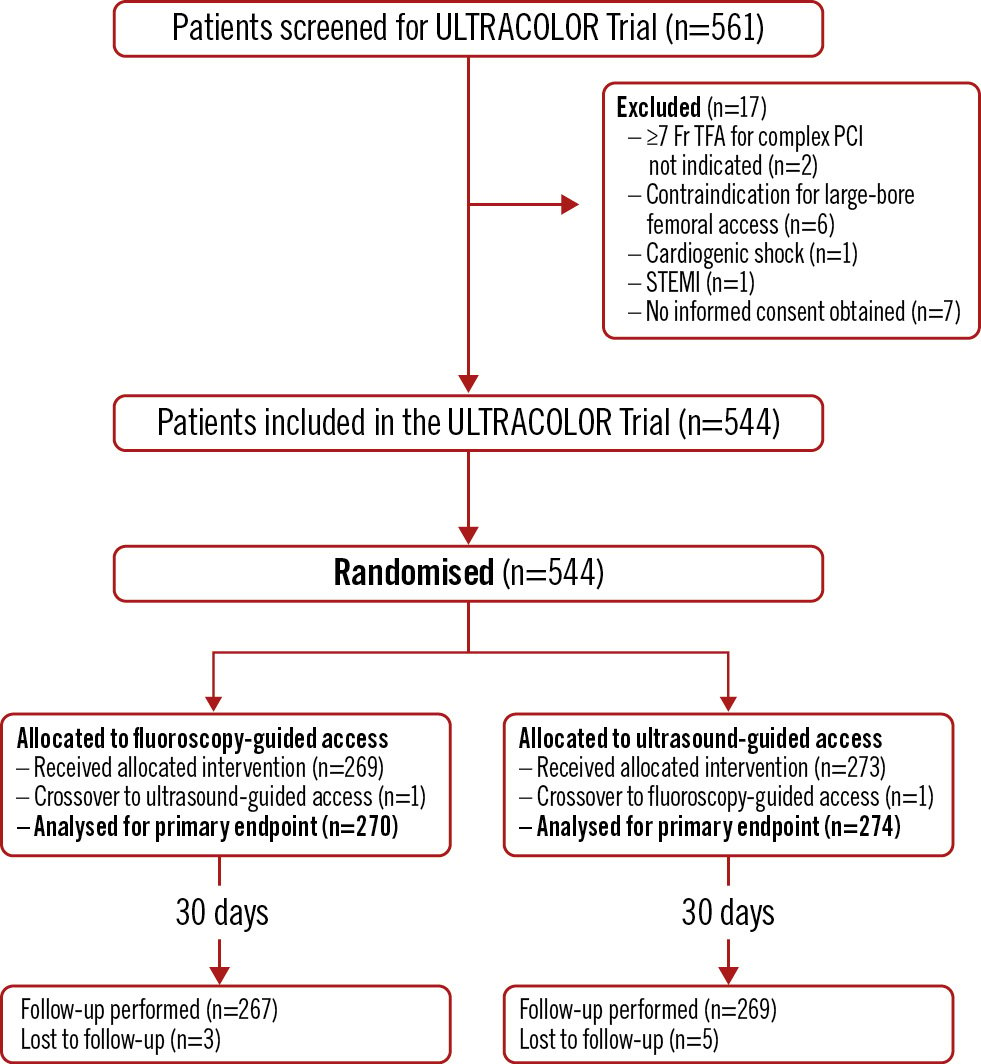

From June 2021 to March 2023, 561 patients were screened for inclusion, of which 544 patients were included and randomised to either ultrasound-guided (274 patients) or fluoroscopy-guided (270 patients) large-bore transfemoral access, as represented in the enrolment flow diagram (Figure 1). The median age was 71 years, and 76% were male. The primary indication for complex PCI was stable angina (71%). Most patient characteristics were evenly distributed in both treatment groups (Table 1), except for previous coronary artery bypass grafting (13% in the fluoroscopy-guided and 21% in the ultrasound-guided group; p=0.02).

Figure 1. Enrolment flow diagram for the ULTRACOLOR Trial. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TFA: transfemoral access

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Fluoroscopy-guided (n=270) | Ultrasound-guided (n=274) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 71 [62-77] | 72 [64-78] |

| Male | 209 (77) | 205 (75) |

| Height, cm | 174 [168-181] | 174 [168-179] |

| Weight, kg | 82 [75-93] | 83 [73-95] |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28 [25-30] | 28 [25-31] |

| Medical history | ||

| Hypertension | 197 (73) | 208 (76) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 194 (72) | 201 (73) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 80 (30) | 78 (28) |

| Current smoker | 47 (17) | 48 (18) |

| Family history of CAD | 110 (41) | 102 (38) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 40 (15) | 39 (14) |

| Previous MI | 95 (35) | 102 (37) |

| Previous PCI | 126 (47) | 128 (47) |

| Previous CABG | 36 (13) | 58 (21) |

| Previous stroke | 12 (4) | 23 (8) |

| Indication for complex PCI | ||

| Chronic coronary syndrome | 239 (88) | 236 (86) |

| Stable angina | 188 (70) | 196 (72) |

| Heart failure | 12 (4) | 11 (4) |

| Arrhythmia | 14 (5) | 7 (3) |

| Other | 25 (9) | 22 (8) |

| NSTE-ACS | 31 (12) | 38 (14) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | ||

| Poor (<30%) | 7 (2) | 12 (4) |

| Moderate (30-50%) | 71 (26) | 81 (30) |

| Good (>50%) | 174 (64) | 161 (59) |

| Unknown | 18 (8) | 20 (7) |

| Laboratory results | ||

| Hb, mmol/l | 8.7 [8.0-9.4] | 8.7 [8.1-9.2] |

| MDRD, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 77 [61-88] | 71 [58-83] |

| Thrombocytes, x109 | 229 [184-272] | 233 [191-278] |

| Reason for large-bore femoral access | ||

| Radial artery(ies) too small | 24 (9) | 25 (9) |

| Radial artery(ies) occluded/not palpable | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Double radial access was not standard practice for hybrid CTO | 136 (51) | 133 (49) |

| Operator preference | 88 (32) | 81 (30) |

| Patient preference | 11 (4) | 19 (6) |

| Previous radial access issues | 9 (3) | 13 (5) |

| Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR]. BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; cm: centimetres; kg: kilograms; CTO: chronic total occlusion; Hb: haemoglobin; IQR: interquartile range; m: metres; MI: myocardial infarction; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention | ||

VASCULAR ACCESS CHARACTERISTICS

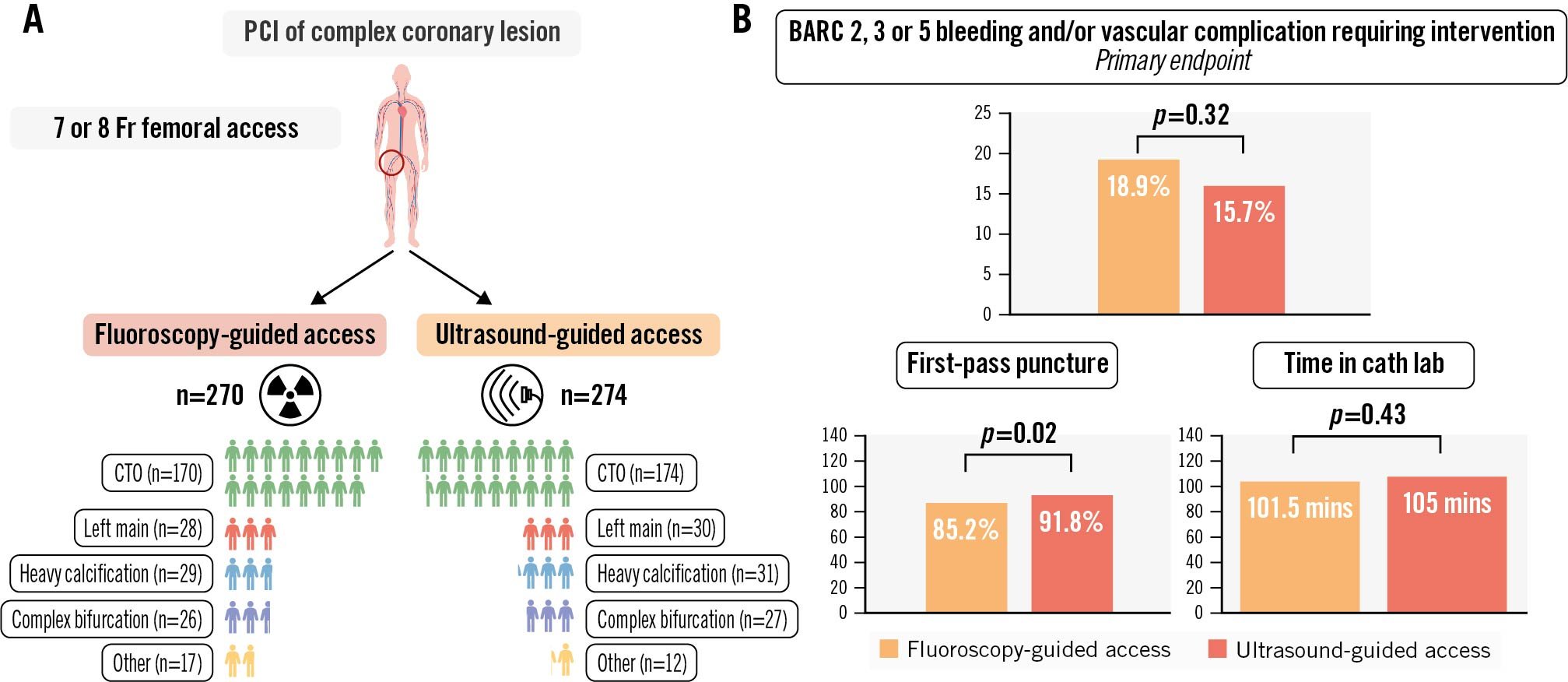

The right femoral artery was predominantly used as the primary access site (92%). An additional arterial access site was used in 56% of patients, of whom 21% had femoral and 79% radial secondary access. One patient in each group (<1%) crossed over to the other randomised strategy. Micropuncture was used in <1% of patients. The first-pass puncture success rate was higher in the ultrasound-guided group (92% vs 85%; p=0.02) (Central illustration). The median number of attempts was 1 in each group (interquartile range [IQR] 1-1). The median time to access was 60 seconds (IQR 60-135) for ultrasound-guided access and 60 seconds (IQR 60-150) for fluoroscopy-guided access. A high puncture occurred significantly more often in the ultrasound-guided access group (5% vs 1%; p=0.03), while a low puncture occurred more often in the fluoroscopy-guided group (10% vs 5%; p=0.02). Accidental venepuncture occurred in 4% of patients with fluoroscopy-guided access versus 2% with ultrasound-guided access (p=0.18). The Angio-Seal (Terumo) VCD was the most applied haemostasis technique in both randomisation groups, and its use was evenly distributed (fluoroscopy 82% vs ultrasound 81%). VCD failure occurred in 6% of the fluoroscopy-guided procedures and in 5% of the ultrasound-guided procedures (p=0.67). The median NRS for access site pain was 0 in both groups. A complete overview of access site characteristics is represented in Table 2.

Central illustration. Outcomes of patients undergoing fluoroscopy-guided or ultrasound-guided large-bore femoral access in complex PCI − the ULTRACOLOR Trial. A) Patient characteristics after randomisation. B) Main outcomes. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; cath lab: catheterisation laboratory; CTO: chronic total occlusion; mins: minutes; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Table 2. Access site characteristics.

| Fluoroscopy-guided (n=270) | Ultrasound-guided (n=274) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site of femoral access | 0.02 | ||

| Right | 255 (94) | 244 (89) | |

| Left | 15 (6) | 30 (11) | |

| Crossover | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0.99 |

| Sheath size for primary access | 0.74 | ||

| 7 Fr | 230 (85) | 236 (86) | |

| 8 Fr | 40 (15) | 38 (14) | |

| Secondary access site used | 145 (54) | 161 (59) | 0.25 |

| Radial | 126 (87) | 117 (73) | 0.002 |

| Femoral | 19 (13) | 44 (27) | 0.002 |

| Sheath size for secondary access | 0.63 | ||

| ≤6 Fr | 59 (41) | 70 (44) | |

| 7 Fr | 85 (58) | 89 (55) | |

| 8 Fr | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) | |

| Micropuncture technique | 1 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 1.00 |

| First-pass puncture | 230 (85) | 251 (92) | 0.02 |

| Accidental venous puncture | 10 (4) | 5 (2) | 0.18 |

| Number of attempts | 1 [1-1] | 1 [1-1] | 0.19 |

| Time to access, secs | 60 [60-150] | 60 [60-135] | 0.86 |

| Puncture height | |||

| Low | 27 (10) | 13 (5) | 0.02 |

| Middle | 194 (72) | 204 (74) | 0.45 |

| High-middle | 45 (17) | 43 (16) | 0.77 |

| High | 4 (1) | 13 (5) | 0.03 |

| No iliofemoral angiography performed | 0 | 1 (<1) | |

| Haemostasis technique | 0.54 | ||

| Angio-Seal VCD | 221 (82) | 222 (81) | |

| Other VCD | 23 (8) | 30 (11) | |

| Manual compression | 26 (10) | 23 (8) | |

| Reason not to use VCD | |||

| Calcifications | 12 (46) | 10 (44) | 0.63 |

| Possible complication | 5 (19) | 4 (17) | 0.72 |

| Bleeding | 2 (8) | 3 (13) | 0.67 |

| Low puncture | 7 (27) | 6 (26) | 0.75 |

| Primary closure technique failure* | 17 (6) | 15 (5) | 0.67 |

| Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR]. *See Supplementary Appendix 2 for definition. Fr: French; IQR: interquartile range; secs: seconds; VCD: vascular closure device | |||

LESION AND PROCEDURAL CHARACTERISTICS

CTO was the most frequent type of complex coronary lesion (63%), followed by heavy calcification (11%), left main stem (11%) and complex bifurcation (10%). The types of complex coronary lesions were evenly distributed between study groups (Table 3). The same applies for the CTO lesion complexities (median Japanese CTO [J-CTO] score 2.0 [IQR 1-3]), left main lesions and complex bifurcation lesions. The other angiographic characteristics were also evenly distributed (Supplementary Table 1). The median procedural duration was 75 minutes (IQR 55-120) for ultrasound-guided access and 75 minutes (IQR 50-120) for fluoroscopy-guided access. The total time in the catheterisation laboratory was 105 minutes (IQR 75-150) for ultrasound-guided access and 102 minutes (IQR 74-148) for fluoroscopy-guided access (p=0.43). Angiographic success was achieved in 94% of patients. The success rates for patients with CTO PCI and non-CTO complex PCI were 91% and 99%, respectively. No difference was observed between the two randomised strategies regarding procedural success. During the procedure, clopidogrel was the most common P2Y12 inhibitor (82%), and 6% had uninterrupted vitamin K antagonist or direct oral anticoagulant therapy. Anticoagulant use and activated clotting time (ACT) levels were comparable between both groups (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3. Lesion and procedural characteristics.

| Fluoroscopy-guided (n=270) | Ultrasound-guided (n=274) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion type | |||

| CTO | 170 (63) | 174 (64) | 0.85 |

| J-CTO score | 2 [1-3] | 2 [1-3] | 0.42 |

| Left main stem | 28 (10) | 30 (11) | 0.89 |

| Heavy calcification | 29 (11) | 31 (11) | 0.90 |

| Complex bifurcation | 26 (10) | 27 (10) | 0.99 |

| Other complex lesion | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.76 |

| No PCI performed | 15 (5) | 10 (3) | 0.29 |

| Angiographic success | 243 (95) | 245 (93) | 0.23 |

| Haemodynamic mechanical support used | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) | 0.75 |

| Impella | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | |

| ECLS | 0 | 0 | |

| IABP | 0 | 1 (<1) | |

| Procedural duration, mins* | 75 [50-120] | 75 [55-120] | 0.44 |

| Total time in cath lab, mins* | 102 [74-148] | 105 [75-150] | 0.43 |

| Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR]. *See Supplementary Appendix 2 for definition. CTO: chronic total occlusion; ECLS: extracorporeal life support; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; IQR: interquartile range; J-CTO: Japanese chronic total occlusion; mins: minutes | |||

CLINICAL OUTCOME AT DISCHARGE

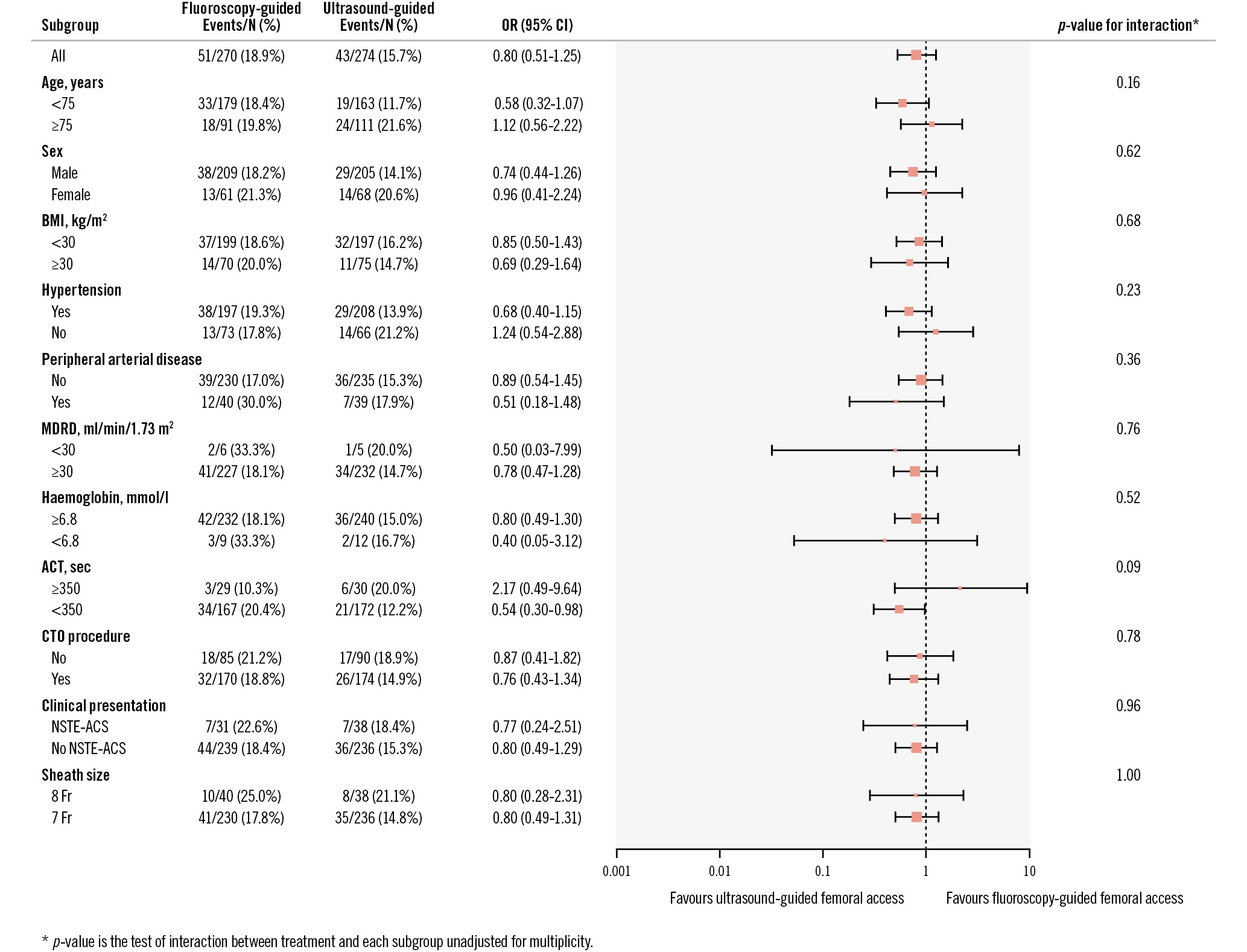

At discharge, the occurrence of the primary endpoint was 15.7% in the ultrasound-guided group versus 18.9% in the fluoroscopy-guided group (p=0.32). The individual components of the primary endpoint were not significantly different between both groups, and the same applies for BARC 1 bleeding (15% for fluoroscopy-guided vs 17% for ultrasound-guided; p=0.53). The occurrence of MACE during hospitalisation was 3% in the fluoroscopy-guided group and 1% in the ultrasound-guided group (p=0.14). Secondary access site-related BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding or vascular complications requiring intervention occurred in 2% of the fluoroscopy-guided group and 4% of the ultrasound-guided group (p=0.34). Vascular complications not requiring intervention were also comparable for both primary and secondary access sites (respectively, 0% and 0% for fluoroscopy-guided access, and 0.7% and 0% for ultrasound-guided access). The clinical outcome parameters at discharge are displayed in Table 4. Delayed discharge (21.0% for fluoroscopy-guided and 21.5% for ultrasound-guided access; p=0.91) and additional imaging of the access site (11% vs 9%; p=0.60) were comparable for both groups (see Supplementary Table 3 for details). The median NRS score for primary access site pain at discharge was 0 for both randomised strategies. No significant interaction with the primary outcome was observed for the prespecified subgroups (Figure 2).

Table 4. Clinical outcome during hospitalisation.

| Fluoroscopy-guided (n=270) | Ultrasound-guided (n=274) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary access site BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding or vascular complication requiring intervention | 51 (18.9) | 43 (15.7) | 0.32 |

| Any primary access site bleeding | 90 (33) | 90 (33) | 0.83 |

| BARC 1 | 41 (15) | 47 (17) | 0.53 |

| BARC 2 | 43 (16) | 34 (12) | 0.24 |

| BARC 3 | 6 (2) | 9 (3) | 0.44 |

| BARC 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Primary access site vascular complication requiring intervention | 6 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.54 |

| Primary access site pain (NRS) | 0 [0-0] | 0 [0-0] | 0.85 |

| Secondary access site BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding or vascular complication requiring intervention | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 0.34 |

| MACE | 8 (3) | 3 (1) | 0.14 |

| Death (all causes)* | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1.00 |

| MI* | 8 (3) | 2 (1) | 0.06 |

| Repeated revascularisation* | 0 | 0 | |

| Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR].*Hierarchical representation of individual MACE components. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; IQR: interquartile range; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; NRS: numeric rating scale | |||

Figure 2. Subgroup analyses at discharge. ACT: activated clotting time; BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval, CTO: chronic total occlusion; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; OR: odds ratio

FOLLOW-UP OUTCOMES

Follow-up was completed in 99% of patients with a median follow-up duration of 32 days. The occurrence of primary access site BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding or vascular complications requiring intervention at follow-up did not show a statistically significant difference between the fluoroscopy-guided and ultrasound-guided group (21% vs 16%; p=0.19). The MACE rate at follow-up was 4% in the fluoroscopy-guided group and 3% in the ultrasound-guided group (p=0.32). The median NRS for access site pain was 0 in both groups. Further specification of the clinical outcome at 30-day follow-up is presented in Table 5. No significant interaction with the primary outcome was observed for the prespecified subgroups at 30-day follow-up (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 5. Clinical outcome at follow-up.

| Fluoroscopy-guided (n=270) | Ultrasound-guided (n=274) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up performed | 267 (99) | 269 (98) | 0.49 |

| Time to follow-up, days | 32 [29-36] | 32 [29-36] | 0.55 |

| Primary access site BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding or vascular complication requiring intervention | 55 (21) | 44 (16) | 0.19 |

| Any primary access site bleeding | 98 (36) | 94 (34) | 0.69 |

| BARC 1 | 45 (17) | 51 (19) | 0.55 |

| BARC 2 | 45 (17) | 34 (13) | 0.16 |

| BARC 3 | 8 (3) | 9 (3) | 0.83 |

| BARC 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Primary access site vascular complication requiring intervention | 7 (3) | 6 (2) | 0.76 |

| Secondary access site BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding or vascular complication requiring intervention | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 0.34 |

| MACE | 11 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.32 |

| Death (all causes)* | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.0 |

| MI* | 9 (3) | 5 (2) | 0.27 |

| Repeated revascularisation* | 0 | 0 | |

| Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR].*Hierarchical representation of individual MACE components. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; IQR: interquartile range; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction | |||

Discussion

ULTRACOLOR is the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing ultrasound-guided with fluoroscopy-guided large-bore TFA for PCI of complex coronary lesions, including a large subset of CTO lesions. In the current trial, ultrasound-guided puncture did not significantly reduce clinically relevant bleeding and vascular complications. The same applies for the secondary safety outcomes, including MACE. However, ultrasound-guided access resulted in increased first-pass puncture success. Overall, our results are in line with recent RCTs, albeit with standard sheath sizes and less complex lesions. The UNIVERSAL RCT demonstrated no significant benefit in clinically relevant bleeding for ultrasound-guided access compared to fluoroscopy-guided access, but it showed improved first-pass puncture success for ultrasound-guided access11. Other recent RCTs showed similar results. This includes a trial by Marquis-Gravel et al which randomised 129 patients requiring TFA to either ultrasound-guided access or landmark-guided access and showed no benefit in significant bleeding15. The Standard versus Ultrasound-guided Radial and Femoral access in coronary angiography and intervention (SURF) trial by Nguyen et al also did not demonstrate a benefit in major bleeding or MACE, but once again, higher first-pass puncture success and a lower number of attempts for ultrasound-guided access were seen16. Recently, two meta-analyses were published regarding ultrasound-guided versus non-ultrasound-guided femoral puncture in coronary procedures. Both incorporated the same nine trials. The individual patient data meta-analysis by d’Entremont et al demonstrated a significant reduction of access site complications in ultrasound-guided access17. However, the incidence of their primary endpoint was mainly driven by large haematomas, which are not associated with increased mortality18. The occurrence of clinically relevant BARC 2 and 3 bleeding events was not significantly lower when ultrasound was used, as was also demonstrated by the meta-analysis incorporated in the UNIVERSAL trial publication11. In addition, no benefit of ultrasound could be demonstrated in a subgroup analysis of ≥7 versus <7 Fr access in the meta-analysis by d’Entremont et al, although large-bore access was used in only 7.9% of patients19. These findings are in line with the results of the current trial.

The overall femoral access site complication rate in the current trial was 17.3%, which is slightly lower compared to the Complex Large-bore Radial PCI Trial (COLOR)3. COLOR compared 7 Fr TFA with 7 Fr TRA in a similar study population and showed a 19.1% occurrence of the primary endpoint in TFA patients. One explanation may be the mandatory use of fluoroscopy-guided puncture in the control group of the current trial, which may help to prevent some bleeding and vascular complications. Compared to classical anatomical landmark-guided puncture, fluoroscopy-guided femoral access may reduce the incidence of bleeding and vascular complications202122. The increased experience and proficiency of complex PCI operators with both fluoroscopy-guided and ultrasound-guided femoral artery puncture, supported by the step-by-step manual and training provided to all participating centres, may be another explanation for the slightly lower event rate. The UNIVERSAL trial demonstrated an event rate of 14.5% for their primary endpoint, which is slightly lower than the endpoint of the current trial. This can be attributed to the large proportion of standard-sized sheaths (<7 Fr sheaths were used in 81% of patients) in that trial. Of note, the primary endpoint definition of the UNIVERSAL trial was slightly different from that of the current trial, with the additional inclusion of large haematomas.

The rationale for using ultrasound-guided puncture is to avoid a suboptimal puncture height and puncture in calcified plaques, which are both associated with higher complication rates and failure of VCDs. We were able to observe that sheath placement below the femoral bifurcation occurred significantly less often with ultrasound-guided access, which makes sense as the femoral bifurcation can be directly visualised by ultrasound. However, high sheath placement (above the internal epigastric artery [IEA]) paradoxically occurred more often in the ultrasound-guided group. This may be explained by the fact that the IEA is not easy to visualise with ultrasound, and efforts to avoid a low puncture and/or puncture in a calcified plaque may therefore result in a (too) high puncture. Operators should be aware of this, since a high puncture may increase the risk for retroperitoneal haematoma10. When using ultrasound to select the optimal puncture location, the standard application of both transversal and longitudinal views may reduce the occurrence of an inadvertent high puncture. Of note, in the current trial, a high puncture location did not result in an increased rate of major bleeding or vascular complications.

When a VCD is used for arterial haemostasis, ultrasound-guided puncture may theoretically lower the risk of VCD failure caused by puncture in a calcified plaque or below the femoral bifurcation. A subanalysis of the UNIVERSAL trial was performed for patients in whom haemostasis was achieved using a VCD (53% of the trial population)19. In this subgroup, access site complications were significantly lower when ultrasound-guided access was used. In the current trial, VCD use was high (91%), and no benefit was demonstrated for patients treated with a VCD, possibly because of the low number of patients not receiving a VCD. Primary closure device failure did not differ between the two randomised groups and occurred in 5.9% of the total study population. This is only slightly higher than the 5.3% observed in the Instrumental Sealing of Arterial Puncture Site Closure Device Versus Manual Compression Trial (ISAR-CLOSURE), where 6 Fr sheaths were used, but lower than in the UNIVERSAL trial subanalysis (8.1%) which used 6 Fr sheaths in the majority of patients as well1123.

Other prespecified analyses for a number of subgroups with known high bleeding risk did not show significant interaction with the primary endpoint; this was also probably hindered by small sample sizes. For example, the proportion of patients with obesity (defined as a body mass index [BMI] ≥30) was 27%, which is relatively low when compared to similar trials (41% in the UNIVERSAL trial). In these patients, a correct puncture position as well as haemostasis without the use of ultrasound can be difficult because of the deeper location of the femoral artery. It should therefore be highlighted that for individual cases with high bleeding risk factors, including acute coronary syndrome, obesity, peripheral artery disease, renal insufficiency and female sex, ultrasound-guided femoral access should still be encouraged1724. Future studies focusing on high bleeding risk patients would be relevant and probably require smaller sample sizes to demonstrate the potential benefit of ultrasound guidance, especially with large-bore access. The use of 8 Fr guide catheters in the current study was relatively low (15%), which reflects daily practice as 7 Fr access is usually sufficient to accommodate most (simultaneous) equipment for complex PCI. Whether or not ultrasound guidance has benefits in 8 Fr, or even larger-bore, access, for example, in case of mechanical circulatory support device use (13 Fr to 23 Fr sheath size) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (14 Fr to 20 Fr sheath size), should be investigated in future RCTs.

Current European and American guidelines on myocardial revascularisation do not specifically address or endorse ultrasound-guided femoral access for coronary angiography and/or PCI2526. In our study, even though ultrasound-guided large-bore TFA in complex PCI did not show a significant benefit in clinically relevant access site complications, we found it to be safe and associated with increased first-pass puncture success rates, without any increase in procedural time. As such, its use may still be considered or even encouraged, especially in high bleeding risk patients and for operators inexperienced in femoral access.

Limitations

First, blinding of the randomised strategy to the operator was not possible for obvious reasons, introducing a chance for selection bias. However, all safety endpoints were adjudicated by an independent and blinded CEC.

Second, in a significant proportion of patients, a secondary access site was used, which may have influenced the safety outcomes. However, use of a secondary access was evenly distributed between the two groups, and the primary outcome was dependent solely on the primary access site, which was subject to the randomised strategy.

Third, in this trial the true effect size turned out to be lower than the anticipated 49%, and therefore, it may be underpowered to detect a smaller relative risk reduction for ultrasound-guided puncture with regard to relevant access site-related complications. In addition, the subgroup analyses were hampered by the low sample size.

Fourth, the use of micropuncture was very low in this trial, as it is not common practice in the participating centres. Scarce and conflicting evidence exists about the effect on access site complications when using the micropuncture technique272829.

Fifth, experience and proficiency with using ultrasound may vary among different centres and operators. However, all participating centres and operators were selected based on their experience with complex PCI and access site management, and a step-by-step manual as well as onsite or video training was supplied.

Finally, because of technical issues with simultaneous inclusion in multiple sites, two extra patients were randomised after the official randomisation process was closed. This has been reported to the medical ethics committee and DSMB (Supplementary Appendix 3).

Conclusions

As compared to fluoroscopy guidance, the routine use of ultrasound guidance for large-bore transfemoral access in complex PCI did not reduce clinically relevant bleeding or vascular complications, although it did increase first-pass puncture success. In addition, the crossover rate was very low, and the total time in the catheterisation laboratory and time to access were both comparable, underlining the applicability of ultrasound-guided access in these patients.

Impact on daily practice

Transfemoral access (TFA) remains commonly used when large-bore guide catheters are required for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of complex coronary lesions, especially when large-bore transradial access is contraindicated. Whether the risk of access site complications for these procedures may be reduced by ultrasound-guided puncture is unclear. As compared to fluoroscopy guidance, the routine use of ultrasound guidance for large-bore TFA in complex PCI did not reduce clinically relevant bleeding or vascular complications. Ultrasound guidance was associated with an increased first-pass puncture success rate combined with comparable procedural duration, which supports the feasibility and safety of ultrasound-guided access in these procedures. Further research directed towards the reduction in access site complications during coronary procedures is warranted and should specifically assess preventive strategies in high bleeding risk patient populations.

Funding

Maatschap Cardiologie Zwolle (sponsor)

TOP Medical Consultancy B.V. (unrestricted grant)

Conflict of interest statement

A. Aminian: consulting services for Terumo. A.O. Kraaijeveld: research grants from Xenios AG; lecture fees from Abiomed, Novartis, and Inari; and consultancy fees from Dekra and Boston Scientific. M.A.H. van Leeuwen: speaker/consulting services honoraria from Terumo, Daiichi Sankyo, and Abbott; and research grants from AstraZeneca, Top Sector Life Sciences & Health, Terumo, Top Medical B.V., and Abbott. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.