Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Optimal medical and interventional approaches in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and large (L-) infarct-related arteries (IRAs) remain unclear. This study investigated the management and outcomes of patients with STEMI according to IRA diameter.

The design of this prospective cohort study (France PCI registry; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02778724), conducted in 45 French centres, has been described1. Consecutive patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI from 2014-2022 with available data for IRA diameter were included. Left main or coronary artery bypass grafting IRAs were excluded. STEMI was defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition of MI (4UDMI). The French Persons Protection Committee (IRB00003888) and Data Protection Commission (no. 2014-073) approved the study.

IRA size was defined angiographically at the end of the index procedure. A segment ≥5 mm at the culprit lesion’s site or proximal/distal to it was classified as an L-IRA. Initial reperfusion without stenting, reassessed at 1 month, was defined as minimalist immediate mechanical intervention (MIMI). Follow-up data were collected prospectively by individuals blinded to IRA size.

To capture both ischaemic and bleeding events related to an increased atheromatous burden and a more aggressive management of thrombotic risk, respectively, the primary outcome was net adverse cardiovascular events (NACE; MI [4UDMI], all-cause death, stent thrombosis [definite/probable], major bleeding [Bleeding Academic Research Consortium 3-5], and stroke [per Academic Research Consortium-2]) at 1 year. Secondary outcomes included final Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow, procedural metrics, and individual components of NACE. We also investigated whether procedural characteristics were associated with NACE in the L-IRA subgroup.

Continuous variables, presented as medians, were analysed with Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests; categorical variables using Pearson’s chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Each L-IRA patient was propensity score-matched with three normal (N-) IRA patients using the greedy nearest-neighbour method. The propensity score included baseline characteristics, relevant prognostic factors, and imbalanced variables (standardised mean difference [SMD]>0.2). SMDs were examined before and after matching. Survival curves using Kaplan-Meier estimates were compared using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. Two-sided p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

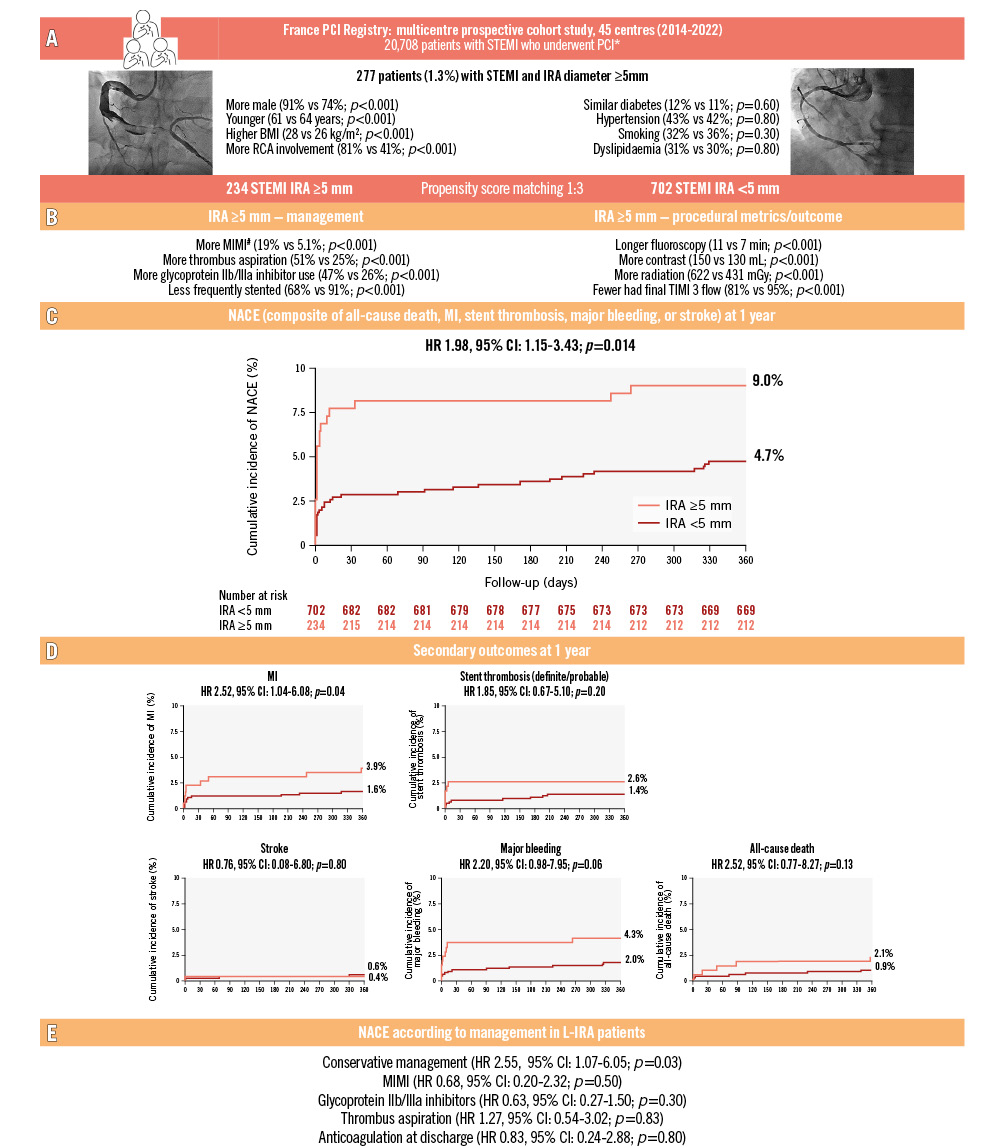

Among 20,708 patients, 1.0% had an IRA <2.0 mm; 4.0% 2-2.5 mm; 16.4% 2.5-3 mm; 40.2% 3-3.5 mm; 29.3% 3.5-4 mm; 7.8% 4-5 mm; and 1.3% (N=277) had an L-IRA. L-IRA patients were significantly younger, more often male, had higher body mass index, and more right coronary involvement (Figure 1A).

Overall, 234 patients with an L-IRA were matched to 702 patients with an N-IRA (all SMDs were <0.2 after matching). Procedural characteristics are detailed in Figure 1B. L-IRA procedures were significantly associated with increased use of contrast agents, radiation exposure, and fluoroscopy time, and TIMI grade 3 flow was less frequently achieved (Figure 1B).

The 1-year Kaplan-Meier estimated NACE rates were 9.0% and 4.7% in the L-IRA and N-IRA groups, respectively (HR 1.98, 95% CI: 1.15-3.43; p=0.014) (Figure 1C). This was driven by more MI and a trend towards more major bleeding (Figure 1D). Two cases were Type 4a MI, the remaining being Type 1 and 4b MI.

In the L-IRA subgroup, patients managed without stents had higher rates of NACE (HR 2.55, 95% CI: 1.07-6.05; p=0.03). There were no significant differences according to MIMI, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, thrombus aspiration, or anticoagulation at discharge (Figure 1E).

An L-IRA was associated with worse outcome, mainly due to increased 30-day NACE, in particular myocardial infarction. This may relate to greater thrombus burden in large vessels, promoting malapposition and rethrombosis. However, L-IRA patients managed conservatively had more NACE – likely reflecting the selection of anatomically complex cases not suitable for stenting and inherently at higher risk – while stent thrombosis rates were similar. This suggests that suboptimal stenting is not the sole contributing factor. Flow disturbances in large arteries may also increase thrombogenicity2. Both mechanisms support more intensive antithrombotic regimens3. In line with this, we observed more anticoagulation at discharge and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor usage in L-IRA patients. However, both strategies were associated with similar outcomes and a trend towards increased bleeding was observed in L-IRA patients. Similar to the previous cohort, L-IRA patients undergoing MIMI exhibited similar NACE4.

These findings highlight the complexity of managing L-IRAs. Procedural challenges include achieving effective thrombus removal and preventing distal embolisation and no-reflow. In the early postprocedural phase, the main concern is balancing rethrombosis prevention with bleeding risk. Further studies on advanced thrombectomy devices (e.g., continuous aspiration, larger lumen catheters) and tailored antithrombotic strategies are warranted to improve outcomes5.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Type 4a MIs may be underestimated, given the difficulty in distinguishing procedural injury from evolving infarction. There was no central review of the angiograms, and the precise phenotype of the IRA was not defined. The 5 mm threshold was used to identify markedly enlarged IRAs, though this cutoff was arbitrary. More objective size assessment would have strengthened the analysis, but intracoronary imaging was infrequently used and quantitative coronary angiography is not routine in France. The observational design precludes conclusions on optimal management. Finally, longer follow-up would be useful to assess rethrombosis risk after dual antiplatelet therapy discontinuation.

In this large, contemporary national registry, STEMI patients with L-IRAs were managed differently and experienced worse procedural and 1-year outcomes.

Figure 1. Management and outcomes of patients with STEMI and large infarct-related arteries – insights from the France PCI Registry. A) Overall population characteristics. B) Procedural management and outcome of matched patients. C) Kaplan-Meier curves according to the size of the IRA for the 1-year primary composite outcome. D) Kaplan-Meier curves according to the size of the IRA for the 1-year secondary outcomes. E) NACE according to management in L-IRA patients. *Patients with documented IRA size. Left main and coronary artery bypass grafting IRA were excluded. #Initial reperfusion without stenting, with IRA reassessed after 1 month, defined MIMI. BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; IRA: infarct-related artery; L-IRA: large infarct-related artery (diameter ≥5 mm); MI: myocardial infarction; MIMI: minimalist immediate mechanical intervention; N-IRA: normal infarct-related artery (diameter <5 mm); NACE: net adverse cardiovascular events; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA: right coronary artery; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

Acknowledgements

Jenny Lloyd (MedLink Healthcare Communications Limited) provided editorial support and was funded by the authors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.