Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Up to one-third of patients referred for transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention (TTVI) have a transvalvular pacemaker (PPM) or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) lead in place. Both the electrophysiology and interventional cardiology communities have been alerted to the complexity of decision-making in this situation due to potential interactions between the leads and the TTVI material, including the risk of jailing or damage to the leads. This document, commissioned by the European Heart Rhythm Association and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions of the ESC, reviews the scientific evidence to inform Heart Team discussions on the management of patients with a PPM or ICD who are scheduled for or have undergone TTVI. Graphical abstract.

Graphical abstract. Jean-Claude Deharo et al. • EuroIntervention 2025;21:1317-1337 • DOI: 10.4244/EIJ-JAA-202501

1. Introduction

The use of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED) has increased exponentially over the past two decades. According to data from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), more than 600 permanent pacemakers (PPM), 100 implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), and 75 cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices are implanted per million inhabitants every year1. A growing body of evidence shows that patients with progressive tricuspid regurgitation (TR) have a poorer prognosis in various clinical scenarios, including left heart failure, multivalvular disease34, and after CIED lead implantation5. Approximately one-third of patients referred for treatment of severe secondary TR have a transvalvular CIED lead implanted, which, in the majority of cases, is not the direct cause of TR (CIED-associated) but may interact during transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention (TTVI). A small but significant subgroup, representing approximately 5–7% of patients with relevant TR, has suspected CIED-related TR and requires specific diagnosis and management67. Both the electrophysiology and interventional cardiology communities have been alerted to the complexity of decision-making in practice when performing TTVI in patients with pacemaker or defibrillator lead(s) crossing the tricuspid valve (TV), due to potential interactions between the leads and TTVI material, including the risk of jailing or damaging the lead(s). At the same time, both communities are becoming increasingly aware of the potential role of CIED leads in the occurrence/ progression of TR. Given the novelty of TTVI techniques, the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) of the ESC have mandated this Task Force to create a Scientific Statement document highlighting the current scientific evidence regarding the increasingly common clinical problem of TTVI in patients with transvalvular CIED leads. The present document is intended to serve as a basis for multidisciplinary discussions between the different healthcare professionals involved in decision-making for the management of patients with CIED scheduled for or undergoing TTVI. It reviews the potential interactions between CIED leads, TV and TTVI materials focusing on the respective risks and benefits of lead jailing and elective lead extraction. Finally, it addresses the most common situations in clinical practice.

2. Interactions between transvalvular cardiac implantable electronic devices leads and the tricuspid valve

2.1. Mechanisms

CIED-related TR is attributed to implantation-related, pacing-related, and device-related mechanisms. The incidence of TR worsening (by 1 or more grades) following CIED implantation vary from 10 to 39%89. Mechanisms are multiple, including: (i) Perforation and laceration of the TV10, presumably occurring during direct introduction of the lead into the right ventricle (RV) rather than ‘prolapsing’ the lead; (ii) Entanglement of the valve or the chordae, particularly when using tined leads11; (iii) Impingement on a leaflet (most commonly the septal one)12; and (iv) Chronic dyssynchronous RV pacing, left ventricular dysfunction, and possibly RV dilatation. New flail leaflet may rarely be observed after implantation. Entanglement and impingement may later translate into fibrous adhesions between the lead and the TV/subvalvular apparatus (Figure 1 and Moving images), resulting in valve dysfunction1013. In addition, following transvenous lead extraction (TLE), TR can be the consequence of leaflet avulsion or chordal rupture. Finally, the presence of a transvalvular lead may predispose to endocarditis, which in turn can worsen TR14. Procedural factors that impact the probability of valve damage include lead tip configuration1516, tined leads being more likely to become entangled or entrapped in the chordae tendinae, and valve crossing technique. Prolapsing may reduce the risk of perforation compared with ‘direct crossing’ because of less head on trauma to the TV leaflets and sub-valvular apparatus17. Technical factors include the number, thickness, stiffness, and course of the lead across the valve.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of interaction between CIED lead and the tricuspid valve. (A) Example of leaflet perforation with the CIED lead piercing the septal leaflet (within the circle) and impairing its mobility. (B) Example of subvalvular apparatus damage during CIED lead positioning causing a flail septal leaflet (indicated by the arrow) due to chordal rupture and severe eccentric TR. (C ) Example of impingement of the septal leaflet through a CIED lead (indicated by the arrow), limiting its systolic mobility and causing severe TR. A, anterior leaflet of the tricuspid valve; CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; P, posterior leaflet of the tricuspid valve; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; S, septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

2.2. Role of type of lead, position, and pacing mode

Studies failed to show clear differences between PPM and ICD leads regarding TV dysfunction despite the higher weight and rigidity of ICD leads181920. Single-chamber RV pacing has been associated with TR progression [14,21–23], presumably due to changes in RV geometry24, a risk that may be mitigated by the use of His bundle pacing25. Although investigated in a small patient population, His bundle pacing might reduce TR25, which has not been observed with left bundle branch stimulation26, especially in the case of a basal lead position27. Even without direct interaction with the TV leaflets, leadless cardiac pacemaker (LCPM) implantation may not fully exclude the occurrence of TR, which may be related to mechanical interference with the subvalvular apparatus28 or to the pacing mode itself, as shown in an observational study including 53 patients followed up to 12 months29. However, a smaller study (N = 23) with shorter observation period failed to show significant changes in RV and TV structure, as well as their function 2 months after LCPM implantation operating in the VVIR mode30.

2.3. Detection of lead-related tricuspid regurgitation

In CIED recipients, a pre-implant imaging assessment is recommended by the 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and CRT31 and it may detect pre-existing TR and help refine the pacing strategy according to TR grade. Although there is no prospective scientific evidence to support this statement, detailed echocardiographic assessment of TV function in the weeks following CIED implantation should be encouraged to diagnose acute damage or adverse interaction with the leaflets or subvalvular apparatus6 and to identify new-onset severe TR that may benefit from early intervention. This applies in particular to patients with technical or clinical risk factor(s) contributing to TR development as summarized in Table 1. Appropriate decisions regarding potential treatment and/or subsequent follow-up may prevent the deterioration of RV function and heart failure symptoms over the long term. Baseline and follow-up information are also crucial, since they will guide decisions in case a TTVI is considered.

Table 1. Risk factors for the development of significant tricuspid regurgitation in cardiac implantable electronic device recipients.

| Technical factors: directly related to CIED lead(s) |

|---|

| Lead placement technique (prolapsing vs. direct crossing) |

| TV passage angle and leaflet interaction32 |

| Multiple leads crossing the tricuspid valve33 |

| Clinical factors associated with TR development: no direct relationship with current CIED lead(s) |

| High burden of RV pacing (>90%)32 |

| Permanent AF34 |

| Pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension34 |

| RV dilatation34 |

| Previous cardiac surgery on left heart valves34 |

| Previous transvenous lead extraction35 |

| AF, atrial fibrillation; CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; RV, right ventricle; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TV, tricuspid valve. |

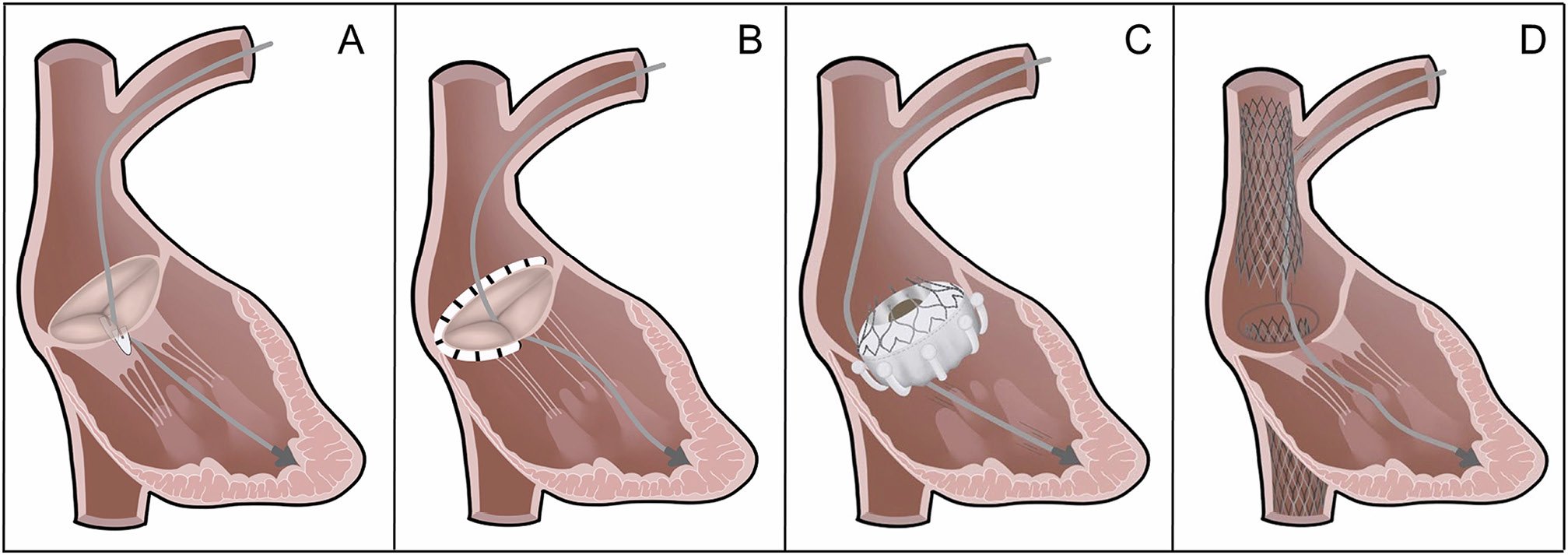

3. Transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions and potential lead issues

While open-heart surgery is the first-line option in low-risk patients, the high mortality associated with TV surgery in higher risk patients, mostly due to patient comorbidities, old age, and late referral36, has encouraged the development of less invasive alternatives. Many TTVI procedures are still under investigation and numbers are expected to increase due to growing disease awareness and an ageing population. Managing patients with CIED leads crossing the TV and causing CIED-related TR, or associated with TR, is challenging and warrants a thorough anatomic assessment before any TTVI. The magnitude of the problem is underscored by the consistently high number of patients with CIED reported in published studies, ranging from 11.8 to 36% (Table 2), even though CIED leads crossing the TV may limit the feasibility of transcatheter repair, particularly when the lead is interacting with the valve leaflets4649505152. There are currently four commercially available transcatheter therapies for TR treatment. Potential interactions of these therapies with CIED leads are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3. (1) Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER): In analogy to its counterpart for the mitral valve, TEER aims to correct TR through leaflet approximation of the TV leaflets. Increasing evidence confirms the safety of tricuspid TEER and its efficacy to reduce TR using the two approved platforms, PASCAL44 and TriClip51 (Figure 2A). A recently published randomized controlled trial (TRILUMINATE) showed that tricuspid TEER using the TriClip system significantly improves quality of life and reduces heart failure hospitalizations at 2 years compared with medical therapy alone. However, no significant change in terms of mortality was observed49. Further research is certainly needed, as this study was designed to include patients with favourable anatomic criteria for tricuspid TEER who appear to have less advanced disease than those included in other commercial and study cohorts53. Approximately 20–30% of TEER procedures are performed in the presence of a CIED lead crossing the TV54. There are two main scenarios42: (a) The lead is an innocent bystander without a causative role in TR. In this scenario, the lead is usually far from the grasping zone and does not hamper leaflet coaptation and motion. Interaction with the lead during valve intervention is usually minimal and does not add risk of device detachment or damage. (b) The lead has a causative role in TR. In this scenario, comprehensive imaging assessment is required to determine whether the lead is attached or fused to a valve leaflet. In case of intact lead mobility, TEER is likely to be successful and often implies displacing and/or fixing the lead into one of the commissures or between two clips (Figure 3). Irrespective of the strategy adopted, a too close interaction of any TEER catheter and a CIED lead should be avoided, in particular when the grippers are in open position. Penetration of the exposed grasping teeth into the lead coating may result in a potentially irreversible entanglement in addition to possible damage to the lead. Valve recrossing can be challenging depending on the number and location of the implants and necessitate echocardiographic guiding. (2) Direct percutaneous annuloplasty: This procedure replicates the prosthetic surgical annuloplasty that addresses annular dilatation occurring in functional TR43. The Cardioband system has shown effective and durable TR reduction, along with substantial symptomatic improvement55 (Figure 2B). Combination with TEER may be needed to optimize TR reduction in patients with advanced disease or those with a persisting pseudo-prolapse. However, annuloplasty can be challenging in the presence of a lead close to the postero-septal or antero-septal area due to problematic visualization during the implant and lead jailing is occasionally unavoidable. This needs to be evaluated carefully since, in addition to lead injury, fixed leaflet impingement leading to TR worsening is sometimes observed. Lead insertion or extraction (if not jailed) after transcatheter annuloplasty is doable. (3) Transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement (TTVR): This procedure aims to address TR through positioning of a transcatheter valve delivered from the femoral or jugular vein (Figure 2C). In the TRISCEND II randomized controlled study investigating the EVOQUE system, 38.2% of the patients treated with TTVR had a CIED lead at baseline56. A new pacemaker (mainly LCPM) was implanted in 27.8% of the pacemaker-naïve patients within 1 year (17.4% of the whole cohort) after the procedure. In the presence of a pre-existing lead across the TV, the CIED is jailed between the annulus tissue and the self-expanding bioprosthesis precluding the option of subsequent lead extraction. (4) Caval valve implantation (CAVI): Caval valve implantation represents a symptomatic treatment option for patients who cannot undergo valve repair or replacement. The goal of this therapy is to mitigate the consequences of TR backflow, improve renal congestion, and better control volume overload (Figure 2D). Beside positive effects on symptoms, reverse RV remodelling has been observed in a prospective observational study. Approximately 22% of patients who receive CAVI have a CIED. Although the presence of leads does usually not mitigate the effectiveness of CAVI, it creates extensive entrapment in the superior vena cava of all intracardiac leads and (atrial) lead dislocation has been described57. Moreover, the presence of a valve that covers the brachiocephalic vein confluence may limit repeat lead implantation.

Table 2. Summary of published studies on transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions in patients with CIED leads.

| Study reference | Patients (N) | Patients with transvenous leads (N) | System used for TTVI | TLE | Patients with jailed leads (N) | Lead complications | New Conduction disturbance | FU duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FORMA37 | 19 | 3 | FORMA | No | None | No issues reported | None reported | Mean 32 months (24– 36) |

| T-TEER in CIED patients38 | 102 | 33 | MitraClip | No | 12/33 clips close to RV lead | Slight increase in thresholds (1 RA, 1 LV, 1 RV) | None reported | 1 day (0–188 days) |

| GATE39 | 5 | 1 | NaviGate system | No | 1 | No change in threshold (died day 28) | 1 temporary PPM and no definitive one | 3–6 months |

| CAVI (Sapien)40 | 25 | 9 | Sapien Single caval (IVC), N = 19 Bicaval, N = 6 | No | Unknown (BiCaval + PPM unknown) | No issue reported | None reported | 316 ± 453 days |

| VIVID Valve in valve registry41 | 329 | 128 with CIED 58 with transvenous leads 31 with leads crossing the TV | Sapien Melody Valve in previous surgical valve repair | 3 before | 28 | Dislodgement: 1 Impedance and threshold increase: 1 Fracture M7: 1 | None reported | Median 15.1 months |

| TriValve42 | 470 | 121 | MitraClip (87%) CAVI FORMA Cardioband NaviGate Pascal | No | Not reported | No dislodgement No dysfunction | None reported | Median 7 months (1.15–20.00) |

| TRI-REPAIR43 | 30 | 4 | Cardioband | No | Not reported | No issue reported | Conduction system disturbance: 2 | 2 years |

| PASTE44 | 235 | 72 | PASCAL | No | Not reported | No lead issue reported; half of the SLDA occurred in patients with leads | None reported | Median follow-up of 173 days |

| 1-year FU with EVOQUE system (compassionate use)45 | 27 | 9 | EVOQUE | No | 9 | No dislodgement No dysfunction | −2 new PPM < day 3 −1 new PPM day 31 | 379 days (197–468) |

| TRISCEND I46 | 176 | 57 | EVOQUE | No | 57 | No information | 15 patients (13.3% of CIED-naïve patients) required new pacemaker implantation | 1 year |

| TRICENTO47 | 21 | 3 + 1 extracted before and implanted with a Micra | Bicaval stent | No (1 before) | 3 | No issue reported | None reported | 1 year |

| TRILUMINATE single arm48 | 98 | 14 | TriClip | No | Not reported | No issue reported | 2 patients received a new pacemaker within 3 years | 3 years |

| TRILUMINATE RCT49 | 175 (170 received the device) | 28 | TriClip | No | Not reported | No issue reported | Not precisely reported (5 new CIEDs at 1 year) | 12 months |

Figure 2. Contemporary transcatheter treatment methods of tricuspid regurgitation and their interaction with CIED leads. (A) Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; (B) Direct annuloplasty; (C ) Transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement; (D) Heterotopic CAVI in both venae cavae.

Figure 3. Examples of interactions between tricuspid devices and CIED lead. (A–B) Implantation of 2 TriClips (*antero-septal coaptation line; **postero-septal coaptation line) with PM lead in-between (arrow); (C ) Jailed PM lead after direct annuloplasty using the Edwards Cardioband system; (D–F ) Interaction between the Lux valve and a jailed CIED RV lead as seen using echocardiography-fluoroscopy fusion imaging (D) and computed tomogram (E–F ).

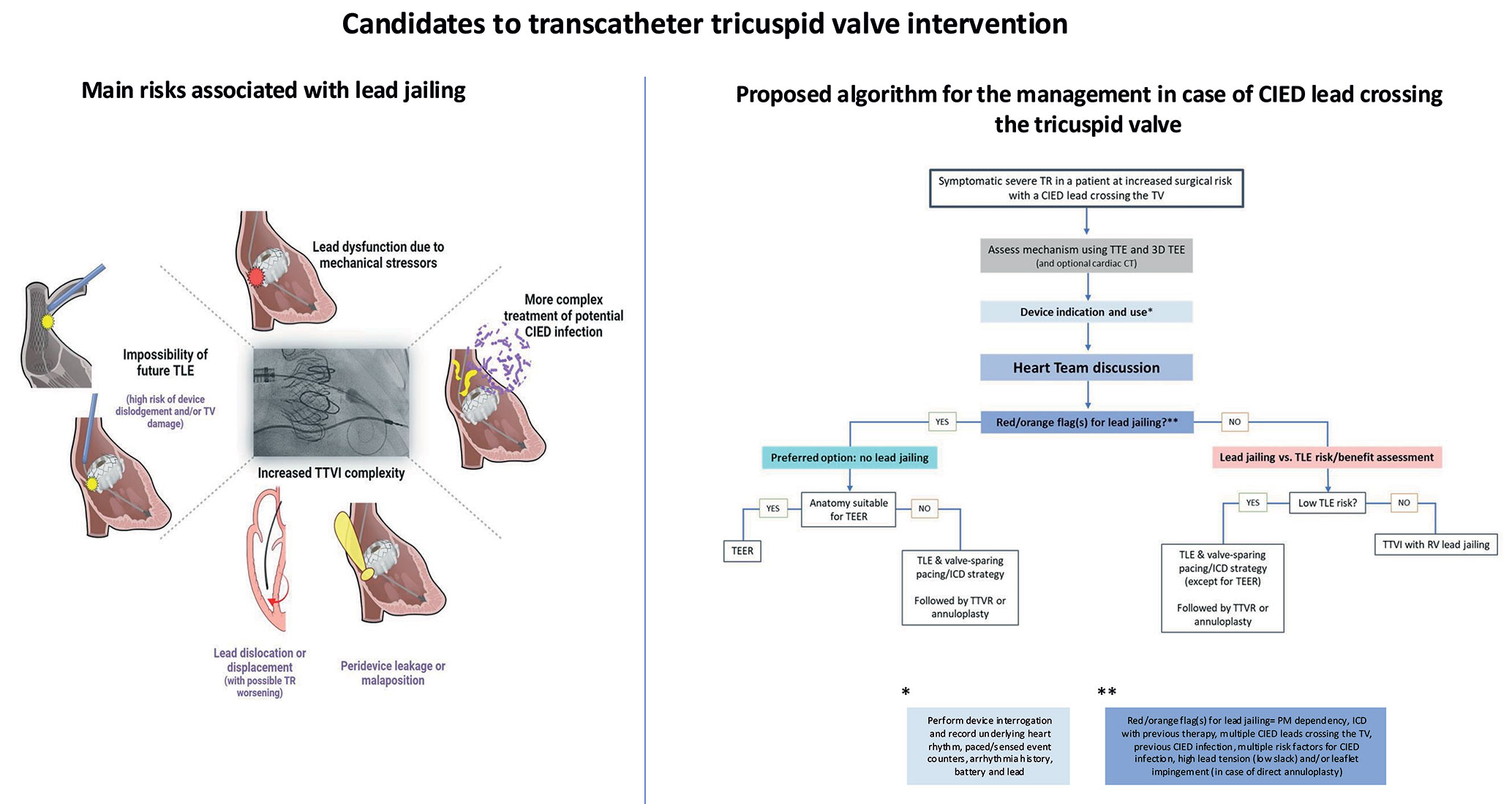

4. Potential risks due to lead jailing and device-lead interaction after transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention

The survival of patients with pre-existing CIED systems continues to improve, and the prevalence of both lead-related and lead-associated secondary TR will continue to rise5. This implies that the number of jailed leads is also expected to increase in the near future. The incidence of lead jailing during TTVI varies from 0 to 33% (Table 2). Although major mechanical or electrical lead dysfunction has been rarely reported, the long-term risk has not been evaluated and is largely unknown. Importantly, no details regarding CIED, including pacing-dependency, lead type or defibrillation coils and indications for CIED therapy, are available in the majority of the studies (Table 2). In a large dataset of 329 patients undergoing tricuspid valve-in-valve or valve-in-ring procedures41, a lead complication rate of 10.7% was observed over a median follow-up of 15.2 months in 28 patients who had jailed leads. Importantly, these patients had their lead jailed between two metallic structures (surgical valve or ring and the stent frame of the newly implanted transcatheter heart valve) and not between metal and tissue as it is the case for TTVI performed in native valves or CAVI. In the largest registry series of patients undergoing TEER, there were no reports of lead damage during short-term follow-up (median 6.2 months), although very limited information on lead type and function is available58. In a small number of patients treated with transcatheter TV annuloplasty, no adverse events related to jailed leads were reported55. At 1 year, no CIED-related complications were described in 9 patients with pre-existing CIED leads who underwent bicaval valve implantation59. The risks associated with CIED lead jailing are summarized in Figure 4. The overall risk of lead damage in this context remains unclear and is potentially related to the lead composition, dwell time and location, as well as the properties of the valve deployed. Transvenous leads are exposed to considerable mechanical and biological stressors within the vascular space, and any tricuspid prostheses jailing them is expected to have additional impact on subsequent lead performance. Lead dislodgement or damage may necessitate revision or replacement, which increases the risk of venous occlusion, as well as infection. Extraction of jailed lead may not be feasible60. The reported rate of mid-term dysfunction is not negligible prompting careful patient and device evaluation before considering lead jailing. This includes patients with complete pacemaker dependency or prior use of ICD for treatment of arrhythmias, as well as those with previous CIED infection. In these situations, if doable, lead extraction may be preferred to avoid lead jailing (Figure 5). Only limited short-term lead safety data exists on leads jailed by stents in both the innominate vein and superior vena cava6162. Case reports for both scenarios have been published at this early stage. Some report lead failure at 2 weeks63, others freedom from failure at 1 year59. Another major concern is the risk of infection with need of lead extraction. The risk of CIED infection increases with re-interventions on the device, from around 1% after the first CIED implantation, and approximately doubling with each additional re-intervention64. Other risk factors for CIED infection are listed in Table 3. Cardiac implantable electronic devices infections are associated with increased mortality66. The number of CIED-infections is expected to increase with the growing pool of CIED-patients and the presence of TTVI material interacting with an infected CIED to complicate treatment. The risk of endocarditis associated with TTVI is not known and existing literature is very limited. There is agreement that CIED infection is best treated with complete CIED system removal67, typically including TLE. One case report presented successful TLE of both a pacing and a defibrillator lead jailed around a surgical tricuspid bioprosthesis in a patient with CIED pocket infection68. However, both leads could be extracted without passing the TV with the extraction sheath. In another case of CIED pocket infection in a patient after TTVR, extraction of the jailed ICD lead was not attempted due to the risk of dislodging and embolizing the bioprosthesis69. We found no published reports on patients with indwelling RV pacing or defibrillator lead(s) who had received TEER and afterwards developed CIED infection with need for TLE. Jailed leads often have long dwell-time and are adherent to the TV leaflets. Percutaneous extraction of jailed leads therefore carries a risk of TV laceration or damage and likely new TR in patients treated with TEER, as well as valve dislodgement after TTVR. There is no literature concerning the risk of TV endocarditis after TTVI in patients with CIED-infection. Case reports indicate that mitral valve endocarditis after transcatheter mitral valve repair has a deleterious prognosis, is best treated by surgery, whereas frequently the alternative of long-lasting antibiotics must be chosen7071. Similarly, extensive valve surgery may not be appropriate in elderly patients undergoing TTVI who will need to be managed conservatively.

Figure 4. Main risks associated with lead jailing during transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions. IED, cardiac implantable electronic device; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; TLE, transvenous lead extraction; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TTVI, transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention; TV, tricuspid valve.

Figure 5. A proposal to assist multidisciplinary discussion: red and orange flags for lead jailing—in these situations transvenous lead extraction requires careful multidisciplinary discussion before TTVI. (*see Table 3). CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; PM, pacemaker; TTVI, Transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention; TV, tricuspid valve.

Table 3. Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device lead infection.

| Risk factors for CIED lead infection ordered from highest to lowest reported risk in each section (adapted from Blomstrom Lundqvist et al, Europace 2020) {65} |

|---|

| Patient-related factors |

| End stage renal disease |

| History of CIED infection |

| Fever prior to implant |

| Corticosteroid use |

| Renal failure |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| NYHA ≥ 2 |

| Skin disorders |

| Malignancy |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Heparin bridging |

| Chronic heart failure |

| Oral anticoagulants |

| Device-related factors |

| Abdominal pocket |

| ≥2 leads |

| Dual chamber device |

| CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; NYHA, New York Heart Association |

5. Risks and benefits of transvenous lead extraction

Lead extraction needs to be carefully evaluated during the planning of TTVI through a multidisciplinary discussion taking into account individual risks of transvenous lead extraction (TLE) and a thorough evaluation of the mechanism and the anatomic relationship between the lead and the valve672.

5.1. Risks of transvenous lead extraction

TLE has evolved during the last 20 years and updated consensus documents with well-defined indications, definitions and outcomes are available7374. It represents the cornerstone of the management of infected and malfunctioning CIED leads757677. European Heart Rhythm Association surveys78 and the ELECTRa (European Lead Extraction Controlled) Registry (N = 3510)79 provided a snapshot of the clinical practices and physicians’ attitudes towards TLE in Europe. Despite the development of different techniques808182838485 and approaches868788, TLE rarely leads to major complications (1.7%) and death (0.5%)899091929394. Patient-related (age, sex, comorbidities, indications)9596979899100 and lead-related factors (dwell time, lead and insulator type, design, fixation mechanisms, coil technologies,) may be associated with different risk profiles (Table 4)101102103104105106107108109110111. The factors with the highest risk are, in decreasing order, female sex, the number of leads to be extracted, the presence of coagulopathy, limited operator or centre experience, and low body mass index. A relationship has been suggested between operator and centre volumes and outcomes112113. Educational pathways73114 have been advocated in order to minimize TLE related complications. Procedure-related major complications including death were more frequent in women, in case of a dwell time >10 years and when powered sheaths or a femoral approach was used for TLE. Several TLE risk stratification tools have been published so far but none is routinely used in clinical practice115116117118119120. These scores show that the lead dwell time (>10 or 15 years for pacemaker leads and >5 or 10 years for defibrillator leads) and their number (increased risk for each lead beyond one) contribute most to the procedural risk. Machine learning may have an incremental value to predict adverse events, but has yet to be applied on large scale populations119. Age has been reported as a factor increasing the risk of complication during TLE, but this factor alone should not be considered a strict exclusion criteria. Indeed, according to a meta-analysis, octogenarians who are the main candidates for TTVI do not seem to have significantly higher mortality and major complications during or after TLE (RR 1.40 and 1.43, respectively, both not statistically significant)121. On the other hand, severe left ventricular dysfunction or advanced heart failure increase the risk of complications (by a factor of 2) and the risk of 30-day mortality (by a factor of 1.3–8.5)75.

Table 4. Risk factors for severe transvenous lead extraction complication.

| Risk factors for severe TLE complication (adapted from Deharo et al, Europace 201273 and Kusumoto et al. Heart Rhythm 201775 |

|---|

| Patient-related factors |

| Low body mass index (<25 kg/m2) |

| Female sex |

| Comorbidities, age, poor LV function, renal failure, coagulopathy, large vegetations |

| Occluded or severely stenosed venous access |

| Congenital heart disease with complex cardiac anatomy |

| Prior cardiac surgery lowers the risk of complications |

| Technical factors |

| Number of leads present or extracted |

| Passive fixation mechanism |

| Lead body geometry (non-isodiametric) |

| ICD lead |

| Dwell time greater than 1 year |

| Special/damaged/deficient leads |

| Limited operator and centre experience |

| LV, left ventricle; TLE, transvenous lead extraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator |

5.2. Risks of tricuspid valve damage due to lead extraction

TLE is associated with a significant increase in the severity of TR in 3.5– 15% of the cases35122123124125126127128, which is likely explained by adherences between the leads and the TV apparatus129. This complication can occur irrespective of the type of the tools used for extraction (passive or mechanical sheath) and is usually due to a new flail leaflet123. The most important risk factors for worsening TR following TLE were longer lead dwell time and multiple leads crossing the TV. The use of several tools in the same patient has also been suggested as a potential cause, but is probably linked to the age of the lead and the complexity of adhesions. The medium-term prognosis of patients exposed to traumatic TR was shown to be changed, with new right-sided heart failure symptoms in a study of 208 patients123, while it was not the case in another smaller study126. The risk of damaging the valvular/subvalvular tricuspid apparatus should be taken into consideration when planning TLE before TTVI. A traumatic lesion of the TV could compromise the effectiveness of subsequent TTVI or even render the patient unsuitable for any transcatheter treatment. It is therefore crucial to carefully reassess patients after TLE to confirm the feasibility of TTVI and the most adequate technique to use. As it is not possible to anticipate all technical difficulties, a TLE procedure may be interrupted if a risk of a serious TV damage is detected.

5.3. Lead extraction to reduce tricuspid regurgitation or prevent jailing

There is limited information on the use of TLE alone as a treatment of chronic lead-related TR. Polewczyk et al. 130 studied the effect of TLE in 119 patients with lead-related TR, which improved in only 35%. Results were similar in another series131, and are even worse when there is coexisting TV annulus dilatation. In this respect, it makes sense that early detection of lead-related TR could allow TLE to be considered before annulus dilatation and extensive fibrosis occur. For the indication of TLE, the exact mechanism of valve dysfunction must be analysed by 3D TEE and potentially CT132133, which also provide information regarding TLE access, in particular the presence of lead fibrosis and vein stenosis132134. In the presence of acute TV dysfunction due to leaflet impingement after CIED implantation, timely TLE (within 6 months) seems appropriate in order to minimize the risk of complication and avoid leaflet scarring. When a lead is anticipated to prevent effective repair with TEER, a multidisciplinary discussion should take place considering the risk and benefits of TLE to facilitate TEER. In cases of TTVR, TLE combined with valve sparing lead implantation, or rarely transvalvular implantation through the new valve, should be weighed against the potential risks associated with lead jailing. Given the uncertainties regarding long-term consequences of jailing, lead extraction should also be discussed before stent placement in the superior vena cava75135.

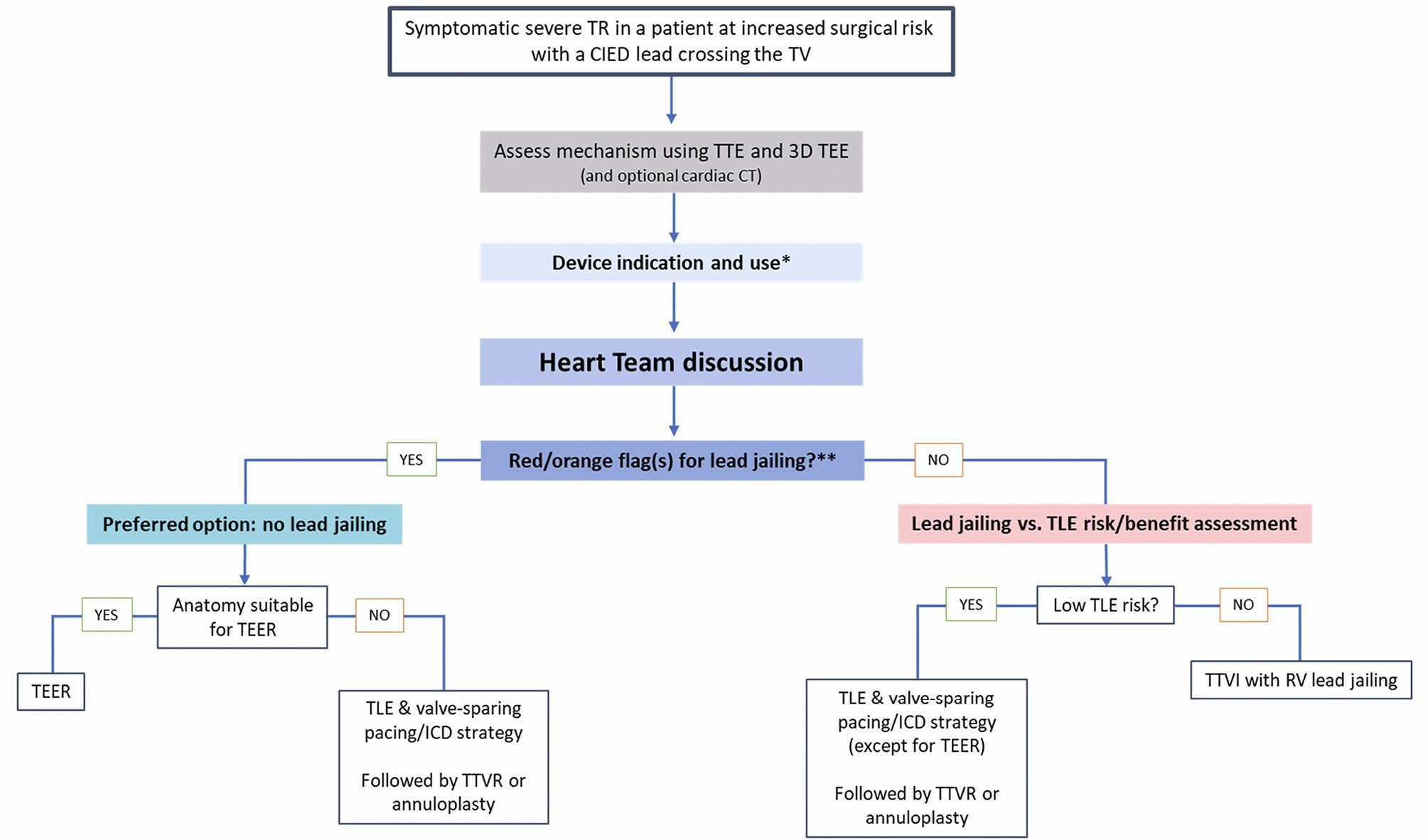

6. Valve-sparing pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator strategies

Valve-sparing alternative pacing strategies have been proposed to mitigate lead-related TR and minimize interaction with implanted tricuspid devices (Table 5)136. Since many patients undergoing TTVI have chronic atrial fibrillation, atrial pacing plays a limited role. Options for long-term ventricular pacing include coronary sinus pacing, surgical epicardial lead placement, LCPM implantation. Coronary sinus pacing presents an appealing option as it avoids valve disturbances. However, challenges such as lead instability, phrenic nerve capture, and high capture thresholds limit its widespread adoption137. For safety, particularly in pacemaker-dependent patients, it may be appropriate to implant two leads in the coronary sinus and use quadripolar lead(s) (see Figure 6). Epicardial lead placement also avoids damage to endocardial structures but necessitates surgical access to the pericardium, which might be difficult in patients indicated for TTVI. In addition, it exhibits higher lead failure rates and often poorer electrical parameters for pacing/sensing compared with conventional transvenous leads and is often not ideal in case of previous heart surgery. Commercially available LCPM systems have low procedural and post-operative complication rates and can also be applied after TTVR (Figure 6). Although unlikely, LCPM implantation does not necessarily exclude the apparition of TV dysfunction29, in particular when implanted in septal position near the tricuspid valve annulus28. In an observational study of 54 patients receiving a LCPM, Arps et al.138 found no alteration in TV function before and after implantation. In a small randomized study, Garweg et al.139 compared 27 patients implanted with a Micra™️ LCPM (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) to 24 other patients implanted with a conventional VVIR pacemaker and found no significant difference in TR between the two systems. Similarly, in a series of 23 patients implanted with a Micra™️ VR or a Nanostim™️ LCPM (Abbott Medical, Chicago, IL, USA), Salaun and colleagues reported no interaction of the devices with TV or RV function or anatomy30. Implanting physicians should be aware of potential interactions between RV LCPM and the material used for TTVI and adapt their implantation technique. A recent small series of patients implanted with LCPM following transcatheter or surgical TV repair or replacement confirms the feasibility and safety of such an approach. It also provides some technical guidance using fluoroscopic landmarks to implant the device at a site distant from the TV apparatus140. In case of the necessity of resynchronization, a total leadless CRT can be delivered with a combination of Micra™️ or Aveir™️ (Abbott Medical, Chicago, IL, USA) and WiSE-CRT™️ (EBR Systems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) systems141. His bundle pacing is another option, enabling a more physiologic electromechanical activation of the ventricles. Studies have shown no alteration of TV function with even TR reduction in some cases25. However, interactions with the TV cannot be ruled out with this technique and implantation may be difficult in case of previous TTVI. Additionally, His bundle pacing leads can be impacted by mechanical disturbances to the conduction system potentially caused by TTVR and will have to be monitored intra- and post-operatively. TV crossing to achieve left bundle branch area (LBBA) pacing (rather than conventional pacing) is an acceptable option in patients with high pacing need or those with reduced LVEF requiring resynchronization. Careful implantation (possibly under echocardiographic guidance) with assessment of valve function may help to overcome the challenges associated with this technique after TTVI142. In the future, LCPM allowing for LBBA pacing may become available. A very limited experience has been reported with the WiSE CRT system, which was not entirely leadless143. If an ICD is necessary, a subcutaneous (S-ICD) or extra-vascular ICD (EV-ICD) are good options. The S-ICD can also be associated with the Empower™️ Leadless pacemaker (Boston Scientific, St. Paul, MN, USA), designed to be paired with the S-ICD to provide pacing or ATP therapies at the time they are needed144. However, this system is currently not commercially available. Transvenous ICD lead placement alternatives exist, including positioning of the defibrillation coil in the middle cardiac vein of the coronary sinus or in the azygos vein, and a coronary sinus lead for sensing and pacing in a coronary sinus branch. Ideally, the options of valve-sparing pacing and ICD therapy should be discussed in CIED candidates with relevant TR who may benefit from TTVI in the future. In these patients, the Heart Team discussion will help selecting the best pacing strategy to avoid leads crossing the TV (i.e. ventricular pacing with a leadless pacemaker or with lead(s) in the coronary sinus branches, subcutaneous, or extravascular ICD therapy). It is reasonable to schedule pacing system interventions such as generator replacement, lead revision, or upgrade procedures prior to the planned TTVI to reduce the risk of infection.

Table 5. Alternative pacing and implantable cardioverter defibrillator strategy in case of percutaneous tricuspid valve intervention.

| Pacemaker alternatives | ICD alternatives |

|---|---|

| Ventricular pacing through coronary sinus | Subcutaneous-ICD (S-ICD™) |

| Epicardial pacing: may allow for dual chamber pacing or CRT | Subcutaneous-ICD (S-ICD™) |

| Leadless pacing (Micra™ or Aveir™): may allow for AV synchrony (Micra AV™) or dual chamber pacing (Aveir DR™) | S-ICD + leadless RV device for ATP and pacing (Empower™) |

| Left ventricular leadless pacing (WiSE-CRT™) Associated with Micra™ or Aveir™: allows for CRT | Transvenous ICD with lead coil in the middle cardiac vein or azygos vein and pace-sense lead in a coronary sinus branch (DF-1/IS-1 connection) |

| CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; AV, atrio-ventricular; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; S-ICD, subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator; RV, right ventricle; ATP, antitachycardia pacing. | |

Figure 6. Proposed algorithm for the management of TTVI candidates with symptomatic severe TR and a CIED lead crossing the TV. *Perform device interrogation and record underlying heart rhythm, paced/sensed event counters, arrhythmia history, battery and lead information (see also Table 6). **Red/orange flag(s) for lead jailing? PM dependency, ICD with previous therapy, multiple CIED leads crossing the TV, previous CIED infection, multiple risk factors for CIED infection, high lead tension (low slack) and/or leaflet impingement (in case of direct annuloplasty) (see also Figure 5). CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; RV, right ventricle; TLE, transvenous lead extraction; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; T-TEER, tricuspid transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; TTVI, transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention; TTVR, transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement; TV, tricuspid valve.

7. Lead management in cardiac implantable electronic devices patients with planned transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention

All CIED patients with transvalvular leads who are planned for TTVI should undergo evaluation by a Heart Team6 consisting of a cardiologist with dedicated TTVI expertise, a cardiac surgeon, a lead extraction specialist and a cardiac imaging specialist (Figure 7). The goal of the discussion is to answer the following questions (1) What is the aetiology of the valvular pathology? Is it lead-related? (2) What is the risk associated with lead jailing depending on lead characteristics and use? Does the planned TTVI require prior TLE to facilitate the procedure and/or avoid lead jailing and what are the risks of such a TLE? (3) Is there a need for urgent temporary pacing during the procedure? (4) What are the options for valve-sparing pacing and ICD therapy? Since TLE may be associated with damage to the leaflets or the sub-valvular apparatus of the TV, as well as serious disabling or life-threatening complications, multidisciplinary evaluation has to integrate a thorough risk-benefit-analysis taking into account life-expectancy, co-morbidities and valvular pathology of the individual patient. In summary, the Heart Team should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of TLE. Examples of scenarios favouring TLE include patients with leads implanted for less than 10 years and those in whom advanced imaging has clearly demonstrated a lead-related TR mechanism.

Figure 7. Example of valve-sparing implantation techniques after transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions. (A) Implantation of a LCPM after TTVR with delivery tool crossing the transcatheter transjugular LUX valve system (RAO). (B) Definitive position of the LCPM in the same case (not shown in this LAO projection, the LCPM is implanted away from the LUX valve system). (C) A pacing lead implanted in a coronary sinus branch after TEER. (D) Two pacing leads implanted in two distinct coronary sinus branches (PPM-dependent patient) after TTVR with the LUX valve system. LAO, left anterior oblique view; LCPM, leadless cardiac pacemaker; RAO, right anterior oblique view; TEER, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; TTVR, transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement.

7.1. Assess TR aetiology and suitability for trancatheter tricuspid valve intervention

Assessment of the mechanism of TR is essential in all patients considered for TTVI. This should be done using transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography in 2D and 3D modes, and CT if necessary. A recent classification proposes a distinct aetiology group for patients with CIED-related TR, in addition to the traditional functional/ secondary and organic/primary TR categories54145. However, determining whether TR is related to a CIED lead can be challenging. Advanced imaging techniques, such as 3D echocardiography and multiplanar reconstructions, help to assess lead position, trajectory and interactions with anatomical structures in real time (Figure 1 and Moving images)146147. In advanced stages, differentiation between lead-related and lead-associated TR may be difficult due to RV remodelling. Cardiac CT, with its higher spatial resolution, can help diagnosing lead-leaflet interaction, measuring the annulus, assessing adjacent structures (e.g. right coronary artery) and anticipating the need for lead jailing148. Although less relevant for TEER149, it is mandatory for the evaluation of valve replacement and annuloplasty. In addition, it is critical to report the number and exact location of CIED leads, as this may influence the treatment strategy.

7.2. Assess cardiac implantable electronic devices function before the procedure

In a patient with a pacemaker or ICD lead, the main risks during TTVR are damaging the lead(s) mainly the ventricular one passing through the TV or dislodgment of the lead(s) related to the catheter manipulation. Damage of the leads may also occur late after the intervention. Before any TTVI, complete details of the implanted system must be available (Figure 7). For ICD, the type and frequency of therapy use should be recorded. Figure 5 highlights the two main periprocedural concerns: pacemaker dependency and the presence of an ICD with prior therapy. In case of full pacemaker dependency, an asynchronous mode can be programmed just before the intervention to avoid sensing interferences. The need for temporary pacing should be anticipated (see specific section). Reassessment of the electrical parameters has to be performed immediately after the procedure, and compared with the pre-operative measurements to detect potential lead(s) dysfunction. Ideally, as the damage of the leads may occur late after the intervention (even if the probability is largely unknown), a remote monitoring follow-up is the preferred option to detect late lead dysfunction.

7.3. Evaluate the need for (urgent) temporary pacing during transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention

Based on device interrogation, in particular if the patient is pacing dependent (i.e. has inadequate or even absent intrinsic rhythm and therefore can suffer significant symptoms or cardiac arrest after cessation of pacing) the risks of lead dislodgement or damage during TTVI should be carefully anticipated150. In general, it seems reasonable to ensure the stability of electrical parameters after CIED implantation whenever possible, if TTVI is planned. After TTVI, new conduction disturbances have been reported (Table 2) and are much more frequent after valve replacement45. Therefore, risk anticipation and preventive measures need to be integrated into pre-procedural planning. In patients considered high risk, i.e. those who are pacemaker-dependent or may become pacemaker-dependent, the interventional team should be prepared to install preventive or bailout temporary pacing strategies that preferably do not cross the TV. This includes preemptive coronary sinus lead placement, as well as emergency pacing options like LV or RV wire pacing6. RV temporary pacing leads should be avoided during TTVR, since lead positioning and retrieval can be challenging. In case of temporary pacing failure, transient patch pacing may be required, but can be generally avoided with adequate planning.

8. Management of a patient with a jailed lead

8.1. Organize multidisciplinary follow-up (inform patient and caregivers)

All CIED patients with jailed lead(s) after TTVI should be evaluated by an electrophysiologist with specific cardiac device expertise, in addition to the interventional cardiologist with TTVI expertise. The multidisciplinary follow-up should focus on: (1) The TTVI material jailing the lead(s), including all details of potential interactions between this material and the implanted lead(s) (2) The indication for CIED implantation and the current underlying cardiac rhythm (i.e. pacemaker dependence or not) and device use (percentage of pacing in each cavity and previous arrhythmia and therapy delivered by the device in the case of an ICD). The team in charge of the follow-up should ensure that the patient and his caregivers are properly informed about potential lead failure75 and/or device infection65. Due to the risks associated with CIED infection, all CIED procedures should be performed using all available preventive measures67. Appropriate follow-up of the CIED and TTVI devices should be planned (see following section) with particular attention to signs of lead failure and interactions between the TTVI material and lead(s) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Proposed algorithm for the management of patients with a jailed RV CIED lead. CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; LBB, left bundle branch; TTVR, transcatheter valve replacement; RV, right ventricle; TLE, transvenous lead extraction; TTVI, transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention.

8.2. Planning for cardiac implantable electronic devices follow-up

An immediate peri-procedural interrogation of the CIED is indicated to detect damage to hardware (Table 6). The 2021 ESC guidelines on earlier detection of technical issues in pacemaker and CRT patients, particularly those at increased risk31. The 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death recommend remote monitoring also for patients with ICD to reduce inappropriate ICD-therapy151. Follow-up of a patient with jailed lead(s) is comparable to a patient with a lead under alert/recall152. In cases where acoustic or vibration-based device alerts are available, they should be activated, and patients instructed accordingly. If alerts and remote follow-up are not available, frequent (every 3 months) outpatient visits are required (Figure 8). Close follow-up is especially relevant in cases of pacing or ICD dependency. Regular echocardiographic exams are required to assess the function of the repaired or replaced TV and whether the jailed lead(s) may affect long-term treatment efficacy (Table 6).

Table 6. CIED follow-up in patients with TTVI and jailed leads.

| CIED interrogation | Pacing threshold |

| Lead impedance | |

| Sensing value | |

| Pacing/sensing percentages | |

| ICD therapies | |

| Oversensing issues | |

| Risk of asystole due to pacing inhibition | |

| Risk of inappropriate ICD therapy | |

| Fluoroscopy | In case CIED interrogation shows abnormalities |

| Echocardiography | Function of the repaired or replaced TV |

| CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; TV, tricuspid valve. | |

8.3. Management and treatment of device-related infection

There is currently insufficient data to guide the management of patients with infectious complications after TTVI. As shown in Figure 8, in this highly concerning situation therapeutic decisions should be taken in a multidisciplinary way and rely on patient status and preferences, as well as the type of infection, which may be limited to the pocket or a bloodstream infection with lead or valve endocarditis. As a first step, the extent of a desired treatment should be defined according to the patient’s preference, especially since the population qualifying for TTVI is elderly and at high surgical risk with multiple co-morbidities (Figure 8). With regard to the management of jailed leads in patients with transcatheter TV devices, when TLE must be performed due to infection, two different scenarios need to be differentiated: infection without TV involvement vs. infection with TV involvement (i.e. TV endocarditis). In patients without signs of involvement of the TV device, an approach with explantation of all parts of the system including transvenous extraction of all leads including jailed leads and preservation of the TV device may be attempted, although challenging68. In patients with infection involving the TV, a curative treatment concept consists of surgical explant of the TV device and surgical TV repair or replacement, as well as CIED explant including extraction of all leads153. In both scenarios, adequate antibiotic therapy is started and maintained, ideally and if possible guided by infectious disease specialists. If CIED reimplantation is needed, valve-sparing reimplantation techniques should be preferred (Figure 8). In patients deemed too frail or unwilling to undergo a TLE attempt (likely a high proportion of the patients undergoing TTVI), long-term suppressive antibiotic treatment can be offered, considering the less favourable infectious prognosis associated with such a strategy153154155. Local ultra-high dose antibiotic administration has been proposed, but the Task Force considers it investigational at this time156.

8.4. Management of malfunctioning jailed leads and upgrade procedures

In case of lead malfunction, an electrophysiologist with specific device expertise should take the most appropriate decision, depending on patient clinical status and the type of lead malfunction, most likely to replace the lead. However, removal of jailed leads is generally not an option and the reimplantation or upgrade (i.e. from conventional pacing to CRT or to ICD therapy) should favour a valve-sparing option (see specific section). For example, for CRT, a coronary sinus lead is preferred to an LBBA pacing lead. For defibrillation, extravascular or coronary sinus/azygous vein options are preferred over endovascular RV defibrillation lead implantation. In the event of vein occlusion and the need for a new lead, venoplasty or implantation of a contralateral lead is mandatory, as TLE is not an option to achieve vein patency.

9. Conclusion

This scientific statement document emphasizes the importance of the Heart Team management and decision-making of TTVI candidates for the treatment of symptomatic severe TR and a lead crossing the TV. Specific scientific data on lead dysfunction, infectious risk and durability of outcomes after TTVI are still scarce and could be improved through dedicated registries. However, “red flags” that may indicate a higher risk of adverse events following lead jailing need to be considered in pre-interventional discussions and alternatives evaluated. TLE before TTVI remains a viable option, integrating the higher risk in this fragile, often elderly patient population. In situations where leads are jailed, frequent monitoring is desirable, particularly in patients who are pacemaker-dependent or who have an ICD indication for secondary prevention.

10. Summary position

Scientific evidence concerning TTVI in patients with CIED leads is scarce and comes from observational studies or first-in-human reports. CIED-related tricuspid regurgitation: Interactions between transvalvular CIED leads and the TV may result into CIED-related TR and predisposing factors have been identified. Physician awareness around this complication and echocardiographic follow-up of patients at risk are needed to allow for early detection and management of CIED-related TR. Potential CIED lead issues with transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions: between 11.8 and 36% of candidates for TTVI have transvenous CIED leads. Attitudes towards lead management in TTVI are heterogeneous due to the lack of scientific evidence. So far, experience with lead jailing is limited but lead failure or dislodgement have been reported and are a matter of concern. High risk situations for lead jailing and the general patient clinical condition should be taken into consideration before final decision. Due to the novelty of the technique, there are very few reports of CIED-related infections in patients with jailed leads and management is uncertain in this high-risk population. The consensual management of CIED infections applies to patients who have had TTVI but the approach must be adapted on a case-by-case basis, particularly in the event of jailed leads. Transvenous lead extraction to prepare for transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention: contemporary data show that complications of transvenous lead extraction are rare but can occur. Peri-procedural mortality is reported at 0.5% and major complications at 1.7%. TR reduction following TLE is unlikely and the TV can be damaged by TLE. Risk factors for complicated TLE need to be taken into account for individualized Heart Team decision-making. Safe and feasible valve-sparing PPM/ICD techniques have been extensively studied out of TTVI. Small series emphasize their role in patients with TTVI. Heart Team discussion and patient engagement: due to the above-mentioned lack of strong scientific evidence in this area, we believe that a Heart Team case-by-case discussion is essential for each patient with a CIED who is scheduled for TTVI. Follow-up of a patient with jailed lead(s) after TTVI needs particular care and dedicated expertise to assess both TTVI result and lead integrity, as well as to manage complications. Due to the novelty and lack of knowledge, CIED patients who are candidates for TTVI should be informed about the benefits and risks of each approach. Need for increased evidence: prospective systematic collection of CIED data in patients included in TTVI studies is encouraged. Reporting of longer-term systematic CIED follow-up data is desirable.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the EHRA Scientific Document Committee: Prof. Katja Zeppenfeld, Prof. Jens Cosedis Nielsen, Dr Luigi di Biase, Prof. Isabel Deisenhofer, Prof. Kristina Hermann Haugaa, Dr. Daniel Keene, Prof. Christian Meyer, Prof. Petr Peichl, Prof. Silvia Priori, Dr. Alireza Sepehri Shamloo, Prof. Markus Stühlinger, Prof. Jacob Tfelt Hansen, and Prof. Arthur Wilde.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Moving image 1. Cine loop Figure 1A

Moving image 2. Cine loop Figure 1B

Moving image 3. Cine loop Figure 1C